Chapter 3: LYMPHATIC SYSTEM

Introduction

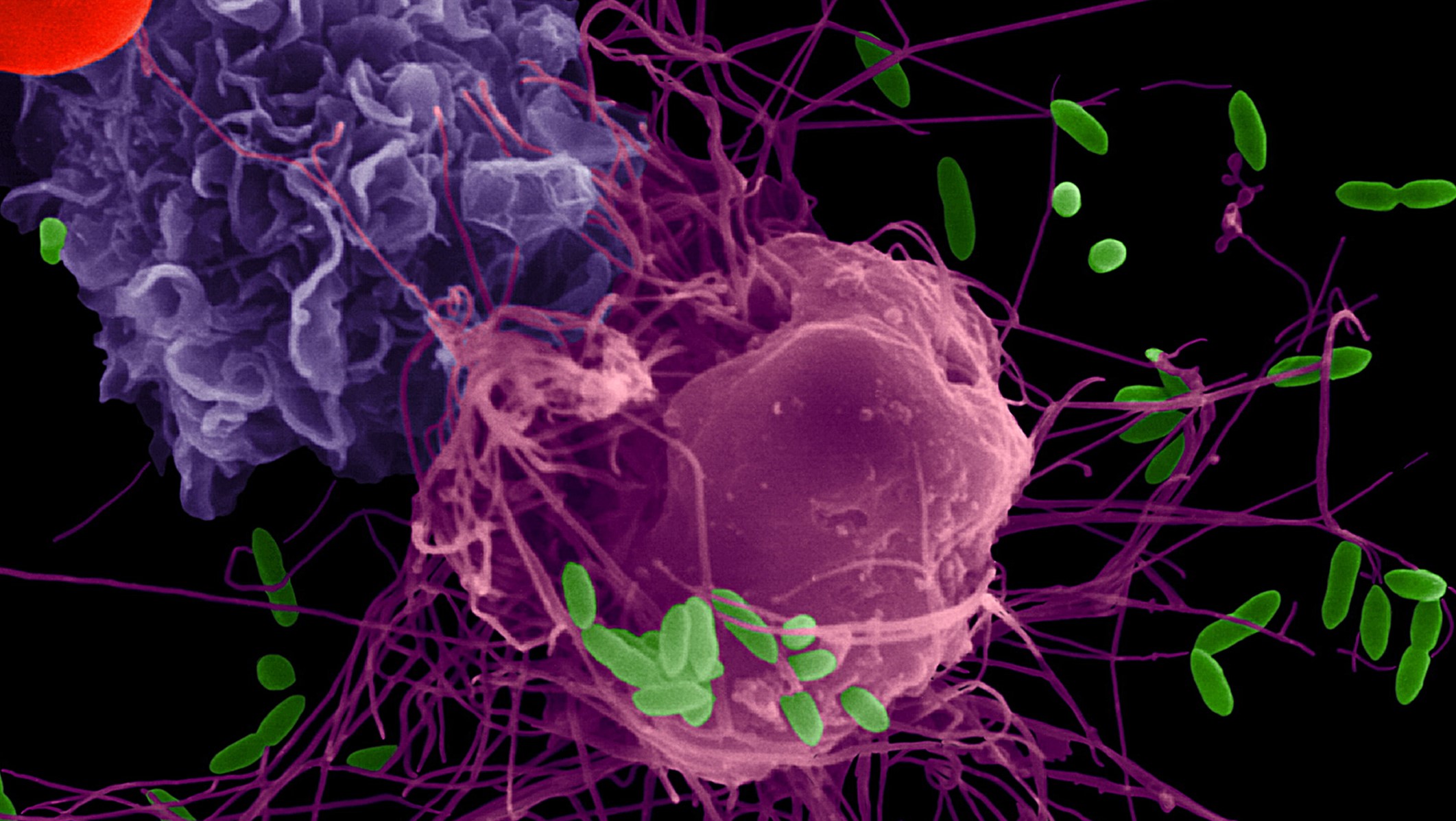

Alveolar immune cells Artificially coloured scanning electron micrograph of the cell and cytoplasmic extensions of a pulmonary monocyte (purple) and macrophage (pink) engulfing foreign infectious cells (green). [https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/common/7/7e/AJRCCM_4-1-17_Cover.jpg]

Chapter Objectives

After studying this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the components and anatomy of the lymphatic system

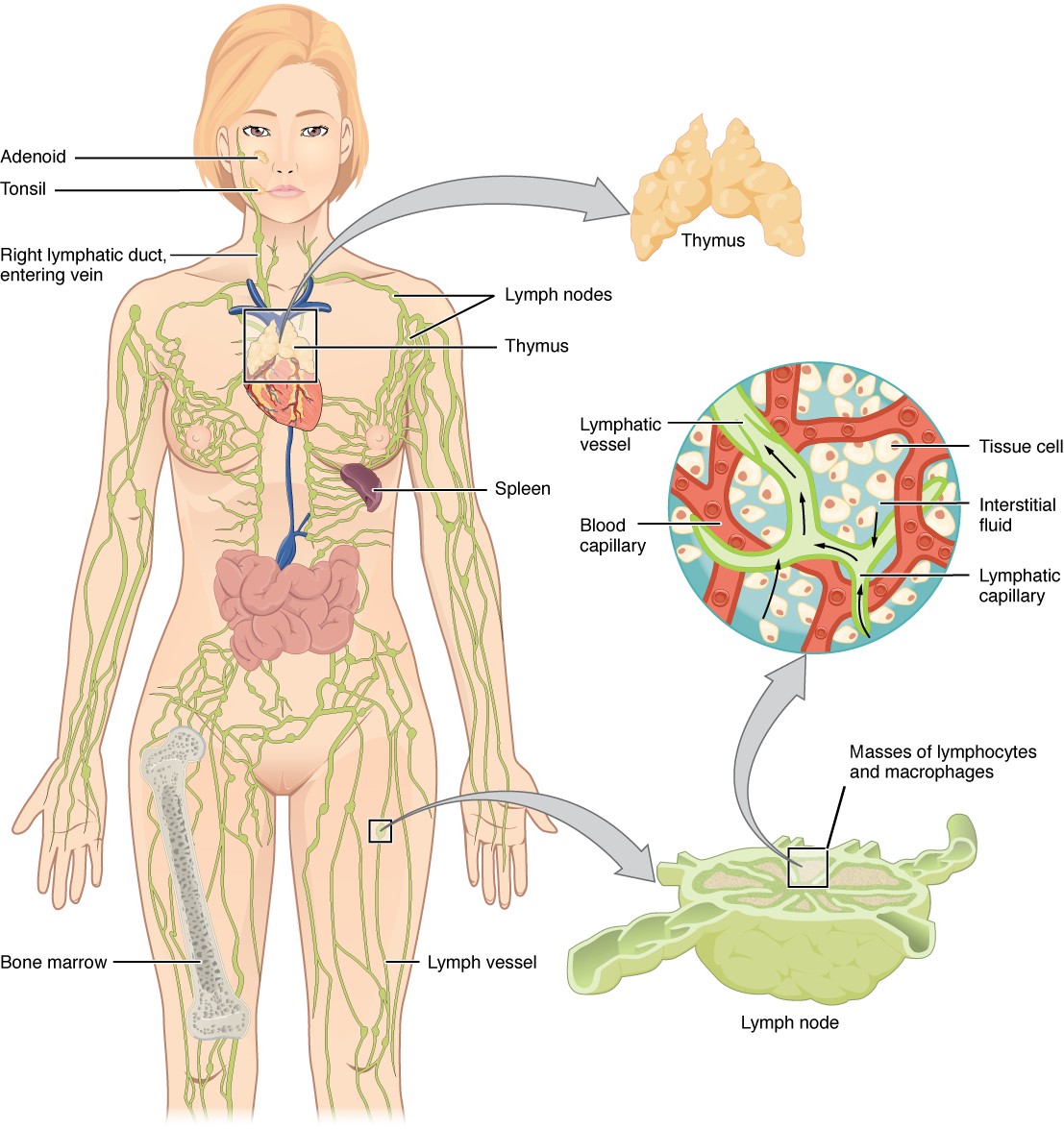

The immune system is the complex collection of cells and organs that destroys or neutralises pathogens that would otherwise cause disease or death. The lymphatic system, for most people, is associated with the immune system to such a degree that the two systems are virtually indistinguishable. The lymphatic system is the system of vessels, cells, and organs that carries excess fluids to the bloodstream and filters pathogens from the blood.

Anatomy of the Lymphatic System

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the location, origin and termination of lymphatic vessels, lymphatic trunks and lymphatic ducts

- Describe the flow of lymph from the intercellular compartments to the venous system

- Describe the function, structure and location of the primary lymphoid organs: bone marrow and the thymus; and secondary lymphoid organs: lymph nodes, spleen and lymphoid nodules;

- Identify the major locations of lymph node groups and describe the microscopic features of a lymph node.

Blood pressure causes leakage of fluid from the capillaries, resulting in the accumulation of fluid in the interstitial space—that is, spaces between individual cells in the tissues. A major function of the lymphatic system is to drain body fluids and return them to the bloodstream via a series of vessels, trunks, and ducts. Lymph is the term used to describe interstitial fluid once it has entered the lymphatic system. A lymph node is one of the small, bean-shaped organs located throughout the lymphatic system. Lymph nodes swell when foreign material is encountered during filtration of lymph.

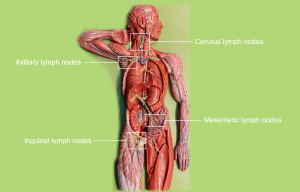

Structure of the Lymphatic System

The lymphatic vessels begin as open-ended capillaries, which feed into larger and larger lymphatic vessels, and eventually empty into the bloodstream by a series of ducts. Along the way, the lymph travels through the lymph nodes, which are commonly found near the inguinal region, axillary region, neck, thorax, and abdomen. Humans have about 500–600 lymph nodes throughout the body (Figure 21.2).

Figure 21.2 Anatomy of the Lymphatic System Lymphatic vessels in the upper and lower limbs convey lymph to the larger lymphatic vessels in the torso.

A major distinction between the lymphatic and cardiovascular systems in humans is that lymph is not actively pumped by the heart, but is forced through the vessels by the movements of the body, the contraction of skeletal muscles during body movements, and breathing. One-way valves (semi-lunar valves) in lymphatic vessels keep the lymph moving toward the heart. Lymph flows from the lymphatic capillaries, through lymphatic vessels, and then is dumped into the circulatory system via the lymphatic ducts located at the confluence of the internal jugular and subclavian veins in the neck.

Lymphatic Capillaries

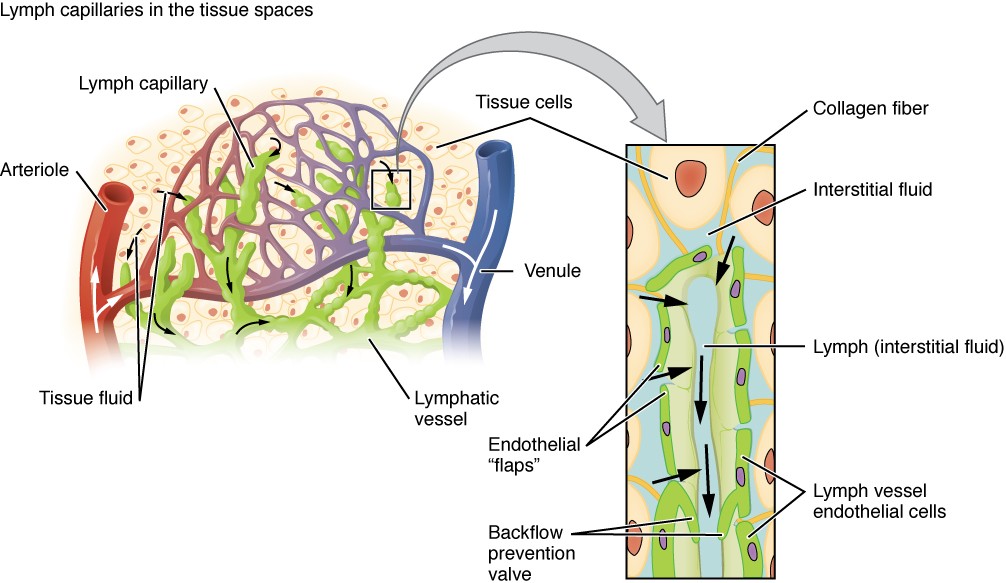

Lymphatic capillaries, also called the terminal lymphatics, are vessels where interstitial fluid enters the lymphatic system to become lymph fluid. Located in almost every tissue in the body, these vessels are interlaced among the arterioles and venules of the circulatory system in the soft connective tissues of the body (Figure 21.3). Exceptions are the central nervous system, bone marrow, bones, teeth, and the cornea of the eye, which do not contain lymph vessels.

Figure 21.3 Lymphatic Capillaries Lymphatic capillaries are interlaced with the arterioles and venules of the cardiovascular system. Collagen fibers anchor a lymphatic capillary in the tissue (inset). Interstitial fluid slips through spaces between the overlapping endothelial cells that compose the lymphatic capillary.

Lymphatic capillaries are formed by a one cell-thick layer of endothelial cells and represent the open end of the system, allowing interstitial fluid to flow into them via overlapping cells (see Figure 21.3). When interstitial pressure is low, the endothelial flaps close to prevent “backflow.” As interstitial pressure increases, the spaces between the cells open up, allowing the fluid to enter. Entry of fluid into lymphatic capillaries is also enabled by the collagen filaments that anchor the capillaries to surrounding structures. As interstitial pressure increases, the filaments pull on the endothelial cell flaps, opening up them even further to allow easy entry of fluid.

In the small intestine, lymphatic capillaries called lacteals are critical for the transport of dietary lipids and lipid-soluble vitamins to the bloodstream. In the small intestine, dietary triglycerides combine with other lipids and proteins, and enter the lacteals to form a milky fluid called chyle. The chyle then travels through the lymphatic system, eventually entering the bloodstream.

Lymphatic Vessels, Trunks and Ducts

The lymphatic capillaries empty into afferent lymphatic vessels that carry lymph to lymph nodes. Lymphatic vessels are similar to veins in terms of their three-tunic structure and the presence of valves. These one-way valves are located fairly close to one another, and each one causes a bulge in the lymphatic vessel, giving the vessels a beaded appearance (see Figure 21.3).

Lymphatic vessels that carry lymph away from lymph nodes are referred to as efferent lymphatic vessels. These eventually merge to form larger lymphatic structures known as lymphatic trunks.

INTERACTIVE ACTIVITY

Explore the image panels of the Lymphatic trunks. This activity requires you to move from one slide to the next. You can do this by clicking either the arrows beside the image, or the buttons below the image. The lymphatic fluid from the left side of the body and the lower half of the right side drains into the thoracic duct via lymphatic trunks. [1st panel]. [Created in Anatomy.TV, Primal Pictures]

Questions:

(a) Describe the flow of lymphatic fluid from the right and left sides of the body including details of the blood vessels though which the lymphatic fluid rejoins the systemic circulation.

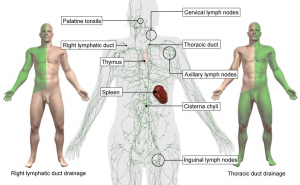

On the right side of the body, the right sides of the head, thorax, and right upper limb drain lymph fluid into the confluence of the right subclavian and right internal jugular veins via the right lymphatic duct (Figure 21.4a). On the left side of the body, the remaining portions of the body drain into the larger thoracic duct, which drains into the confluence of the left subclavian and left internal jugular veins. The thoracic duct itself begins just inferior to the thoracic diaphragm in the cisterna chyli, a sac-like chamber that receives lymph from the lower abdomen, pelvis, and lower limbs by way of the left and right lumbar trunks and the intestinal trunk.

The overall drainage system of the body is asymmetrical (see Figure 21.4b). The right lymphatic duct receives lymph from only the upper right side of the body. The lymph from the rest of the body enters the bloodstream through the thoracic duct via all the remaining lymphatic trunks. In general, lymphatic vessels of the subcutaneous tissues of the skin, that is, the superficial lymphatics, follow the same routes as veins, whereas the deep lymphatic vessels of the viscera generally follow the paths of arteries.

Figure 21.4b Regions of the Body Drained by the Right Lymphatic Duct and the Thoracic Duct

Primary Lymphoid Organs

The primary lymphoid organs are the bone marrow and thymus gland. The lymphoid organs are where lymphocytes mature, proliferate, and are selected, which enables them to attack pathogens without harming the cells of the body.

Bone Marrow

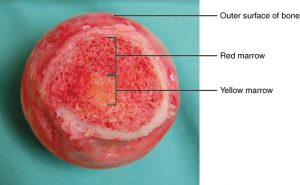

The red bone marrow is a loose collection of cells where haematopoiesis occurs, and the yellow bone marrow is a site of energy storage, which consists largely of fat cells (Figure 21.6). In adults the majority of red bone marrow is located in the flat bones of the skull, the vertebrae, ribs, sternum, os coxae (hip bones) and proximal epiphyses of the humerus and femur. All lymphocytes are produced in the red bone marrow in adults. T-lymphocytes migrate to the thymus for their maturation (T-lymphocyte for thymus) and B-lymphocytes mature in the bone marrow (B-lymphocyte for bone marrow).

Figure 21.6 Bone Marrow Red bone marrow fills the head of the femur, and a spot of yellow bone marrow is visible in the center. The white reference bar is 1 cm. [Modification of work by “stevenfruitsmaak”/Wikimedia Commons]

Thymus

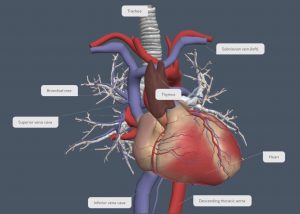

The thymus gland is a bi-lobed organ found in the mediastinum of the thorax, anterior to the aorta and superior vena cava and posterior to the sternum (Figure 21.7).

Figure 21.7 Location of the Thymus The thymus lies superior the heart.

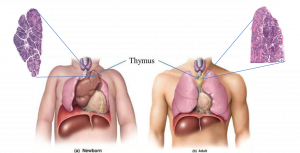

The thymus attains its maximum development around puberty, and then progressively atrophies with the thymic tissue being replaced by fat and connective tissue over time.

Figure XX. Age-related thymus atrophy At birth and during childhood the thymus is a large organ located in the mediastinum. In adulthood, the thymus atrophies and is barely visible in adulthood. [Adapted from A&P Review.]

Secondary Lymphoid Organs

Lymphocytes develop and mature in the primary lymphoid organs, but they mount immune responses from the secondary lymphoid organs.

Lymph Nodes

Lymph nodes function to remove debris and pathogens from the lymph, and are thus sometimes referred to as the “filters of the lymph” (Figure 21.8). Any foreign material that is identified in the interstitial fluid are taken up by the lymphatic capillaries and transported to lymph nodes. Phagocytic cells (phage=’to eat’; cyte=cell) within this organ internalise, destroy and remove any foreign material. Like the thymus, the bean-shaped lymph nodes are surrounded by a tough capsule of connective tissue and are separated into compartments by trabeculae, the extensions of the capsule. In addition to the structure provided by the capsule and trabeculae, the structural support of the lymph node is provided by a series of reticular fibres.

INTERACTIVE ACTIVITY

The major routes into the lymph node are via afferent lymphatic vessels. Cells and lymph fluid that leave the lymph node may do so by another set of vessels known as the efferent lymphatic vessels. Within the cortex of the lymph node are lymphoid follicles, which consist of germinal centers comprised of lymphocytes. The lymph exits the node via the efferent lymphatic vessels.

INTERACTIVE ACTIVITY

Lymph node cross section. Learn more about the structure of lymph nodes by clicking on each information hotspot. [Anatomy.TV, Primal Pictures.]

Question:

(a) Observe the number of afferent lymphatic vessels compared to the number of efferent lymphatic vessels and explain how this structural feature facilitates immune surveillance of large volumes of lymph throughout the body.

Lymph nodes are distributed widely throughout the body with clusters localised in regions.

Figure XX Lymph node clusters Lymph nodes are distributed throughout the body in localised clusters in each region.

Spleen

In addition to the lymph nodes, the spleen is a major secondary lymphoid organ (Figure 21.9). It is about 12 cm long and is located against the thoracic diaphragm in the upper left abdominal quadrant. The spleen is a fragile organ without a strong capsule, and is dark red due to its extensive vascularisation. The spleen is sometimes called the “filter of the blood” because of its extensive vascularisation and the presence of phagocytic cells that remove foreign materials from the blood, including dying red blood cells.

Figure 21.9 Spleen (a) The spleen is attached to the stomach. replace with model

Lymphoid Nodules

The other lymphoid tissues, the lymphoid nodules, consist of a dense cluster of lymphocytes without a surrounding fibrous capsule. These nodules are located in the respiratory and digestive tracts, areas routinely exposed to environmental pathogens.

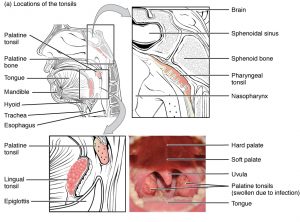

Tonsils are lymphoid nodules located along the pharynx and are important in developing immunity to oral pathogens (Figure 21.10). The tonsil located in the nasopharynx, the nasopharyngeal tonsil, is sometimes referred to as the adenoid when inflamed. The tonsils located in the oropharynx are the palatine tonsils, and the tonsil located in the posterior region of the tongue is the lingual tonsil. These structures accumulate foreign material taken into the body through eating and breathing and help children’s bodies recognise, destroy, and develop immunity to common environmental pathogens so that they will be protected in their later lives. Tonsils are often removed in those children who have recurring throat infections, especially those involving the palatine tonsils on either side of the throat, whose swelling may interfere with their breathing and/or swallowing.

Figure 21.10 Locations and Histology of the Tonsils (a) The pharyngeal tonsil is located on the roof of the posterior superior wall of the nasopharynx. The palatine tonsils lay on each side of the pharynx. The lingual tonsil is located in the posterior region of the tongue.

Key Terms

afferent lymphatic vessels lead into a lymph node

bone marrow tissue found inside bones; the site of all blood cell differentiation and maturation of B lymphocytes

chyle lipid-rich lymph inside the lymphatic capillaries of the small intestine

cisterna chyli bag-like vessel that forms the beginning of the thoracic duct

efferent lymphatic vessels lead out of a lymph node

germinal centres clusters of rapidly proliferating B cells found in secondary lymphoid tissues