6 The SCARF Model: How Change Influences How We Feel in our Roles

SCARF: Status Certainty Autonomy Relatedness Fairness

SCARF: Status Certainty Autonomy Relatedness Fairness

QUOTE: In a world of increasing interconnectedness and rapid change, there is a growing need to improve the way people work together. understanding the true drivers of human social behaviour is becoming ever more urgent in this environment. – David Rock

Since early this century, neurobiologist and coach, David Rock, has been considering the way in which insights from neuroscience can inform coaching and leadership approaches. He suggests that insights from how our brain works can give clues about people’s reactions to change and the potential stressors associated with change. His SCARF model suggests 5 social dimensions around which our brain reacts to potential stressors, ultimately with the intention of minimising threat and maximising reward.

Those 5 Dimensions are

· Status

· Certainty

· Autonomy

· Relatedness

· Fairness

Rock’s view is that responses we see to change or transition in these domains reflect primitive human threat and reward responses of our brain. Understanding this potential reaction can help people prepare for and manage change approaches within teams and workplaces – for example a restructure or a change in policy.

To share an example of this, Rock’s view is that a perceived threat to one’s status – for example, if my position title is changing – will activate similar brain networks as those experienced when there is a threat to one’s physical wellbeing. in the same way, a perceived increase in fairness activates the same reward circuitry as receiving a monetary reward[1].

Activity: Watch this youtube where David Rock explains the model and how to apply this at work.

Let’s have a look at each of the 5 dimensions in turn.

Status

Status is about my perceived importance, sense of identity and perceived ‘place’ in the pecking order of a team or group. A threat response in this domain may be triggered by professional criticism, a change in role title or negative performance feedback. At the same time, a reward response to the ‘Status’ dimension may be experienced if a change in work structure results in a promotion or enhanced role title.

The interesting thing is even small changes can trigger significant reactions in terms of my perceived personal status as this dimension is linked to my ego and identity.[2]

Certainty

All humans like to feel some level of certainty about the road ahead and the way in which we can predict and plan for our future. Of course, recent times have reinforced that ambiguity and lack of certainty is a key feature of modern life.

When we lack certainty, our brain needs to work harder to process more information and variables and we can feel that personal control is diminished. As Rock reminds us, mild uncertainty can motivate us to learn more about a situation; however, too much uncertainty can paralyse activity and negatively influence decision making.

Autonomy

When we perceive that our autonomy has been reduced, we tend to judge that as a threat to our wellbeing. This also adds to our perception of uncertainty. By contrast, when we feel that we have greater autonomy this increases our perceptions of certainty and it also tends to reduce stress.

Relatedness

Humans are social beings. We need and require relationships to survive and thrive. This sense of relatedness is fundamental to our sense of safety. The degree to which we feel safe with others is affected by the nature and quality of these relationships. In the Army and other organizations where not only our sense of safely is a stake but in fact our personal safety is in the hand of those around us, the importance of relatedness is enhanced.

The Army strives to build and emphasise a culture where this relatedness is reinforced as a way of life. This happens through required and encouraged behaviours, symbols and the hierarchies that you live every day.

Increasingly we understand the science, psychology and biology of relatedness. Armies of yore understand the power of relatedness and perhaps imagined or hypothesised about the ‘why’ and now to some degree we know how it works.

In the brain, the ability to feel trust and empathy about others is shaped by whether they are perceived to be part of the same team/tribe.

The brain quickly makes friend or foe decisions.

Strong social connections secrete oxytocin (found in affection, maternal behaviour, generosity, authenticity, trust) disarms the threat response, opens neural connections and helps people to make friends.

Loneliness and isolation are profoundly stressful (perceived by the brain as physical hurt).

Fairness

Fairness is one of the most powerful of the drivers of human behaviours and our beliefs about life

Fairness is a subjective experience that depends on those involved and how they perceive fairness issues1. It also has a strong relationship to the sense of control that people feel in any given situation and whether others are respectful and can be trusted in their use of control over those around them.

We tend to make fairness judgements quickly in situations and particularly when we join a team or a workplace. ‘Fairness’ information is all around us and we are perceptive and responsive to those cues.

We also have a fundamental need to feel certain and we motivated to reduce uncertainty because it can be threatening, and therefore, care more about fairness when they feel uncertain.

So you see that fairness is central to our place in our organization and thus to you in your organisations.

Unfairness generates a strong response in the limbic system, stirring hostility and undermining trust.

As with status, people perceive fairness in relative terms –feeling more satisfied with a fair exchange that offers a minimal reward than an unfair exchange in which the reward is substantial.

Fairness produces reward responses in the brain similar to those that occur from eating chocolate.

Activity:

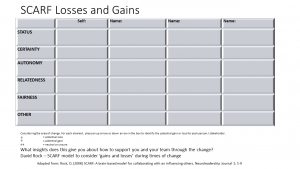

The SCARF is a fundamental approach to use when we are considering change and something ‘new’. Many and perhaps even most changes lead to losses and gains by individuals. It is really important for you to understand the sense that your stakeholders have of the losses and gains they perceive in relation to change and changes.

Change agents often become so involved in the potential benefits of change and innovation proposals that they leave key people behind. This can cause strong resentment and even active resistance and subversion, despite the long term benefits.

At the very least we advise you to use this SCARF losses and gains tool.

This is how it works.

Action 1: Write a short overview of the change including the benefits of the change and also any potential barriers and challenges you believe you might encounter.

Action 2: Create a list of the people, teams and other entities that are involved and in some way affected by the project or initiative. Before you start creating a huge list of stakeholders you would want to create what we at QUT call a ‘salience’ list: the salience list includes those who are clearly the most important to the project, who have power and influence, and those who have a strong interest in either the project being successful or who might have an interest in its failure.

We do recommend that you keep this list private! No one wants to discover that they are on a stakeholder list as an impediment to a project!

Action 3: Choose the top 3 to 5 stakeholders from your list and add them to the SCARF template.

Considering the area of change. For each element, place an up arrow or down arrow in the box to identify the potential gain or loss for each person/stakeholder.

↓ = potential loss

↑ = potential gain

↔ = neutral or unsure

What insights does this give you about how to support you and your team through the change?

David Rock – SCARF model to consider ‘gains and losses’ during times of change

SCARF Losses and Gains Template

This Explanatory pack helps with some additional insights and definitions: SCARF

[1] Rock, D. (2008) SCARF: A brain-based model for collaborating with an influencing others. Neuroleadership Journal 1: 1-9

[2] Rock, D. (2008) SCARF: A brain-based model for collaborating with an influencing others. Neuroleadership Journal 1: 1-9