Introduction to Law

Stephen Bartlett

Introduction to Law

“Suffer any wrong that can be done you rather than come here!”[1]

So begins Charles Dicken’s mesmerising Bleak House. In one of many aspects, the novel critiques the worth of the court of chancery in England in the 19th century. It is a warning about using the judicial system to resolve civil matters; in this case it is the contents of a will. You could also read it as a warning about undertaking this unit.

So, tell the truth, who has misgivings about studying this subject? You’re not lawyers. You don’t want to be lawyers. You want to be HCPs. However, to be a HCP; you know, a good HCP, you must understand substantive (stuff to do with rights and duties) areas of law and normative (stuff to do with process) aspects of our legal system. Additional areas of governance are known as substantive law and normative law. Substantive law relates to behaviour and normative law relates to process and procedure. Substantive law governs rights and duties. Normative law governs the functions of the legal system, in effect the diktat on how the courts function and justice is dispensed as well as rules of evidence and litigation procedures.

This is what the next couple of pages will help you undestand.

We’ve already been introduced to the two main sources of law in Australia: parliamentary law: legislation/statutes/Acts of Parliament and the common law or case law. I should also introduce equity here too, but I might save that and put it out as an optional extra. Parliamentary law is legislation enacted by parliament, it is referred to as an Act of Parliament and it is one of the roles of judges to interpret legislation in cases they hear. Before we go too much further, I need to introduce the Rule of Law and the Separation of Powers.

The rule of law has origins in the Magna Carta. The Magna Carta, and English document originating from the monarch John, King of England dating from over 800 years. The charter promised certain protections from state intervention. Arguably, it was the first step in laws becoming a predictable force as oppose to laws enforced arbitrarily. Democracy, evolving over centuries, begins with the Magna Carta. It was followed by the rule of law. The rule of law established that every person, irrespective of nobility or office held, was subject to its provisions and all people were treated equally under the law. A principle of the rule of law was that laws should be such that all peoples governed by a system of government can governed by such laws.[2] Fundamental concepts are uncontroversial in theory but equality under the rule of law requires normative frameworks to ensure compliance, eliminating abuses of power and despotism.

A further attempt to limit abuses of power, led to the publication by Charles-Louis Montesquieu (1689–1755), an 18th century judge and philosopher, of The Spirit of Laws, which contained his proposal for the separation of powers between:

- Executive – the government or administrative arm, which holds the power to enact legislation

- Legislature – the parliament, which passes bills, votes on legislation for the executive to enact

- Judiciary – the courts, which have powers to interpret and make legal and binding judgments,

Each power is required under the rule of law to execute its own functions. An additional function is that by devolving powers to three separate functioning entities it should the enactment of tyrannical laws. It proposes that in a just society all forms of arbitrary influence or decision-making should be rejected.

For more information on the rule of law and separation of powers please see the links below:

The Spirit of Magna Carta Continues to Resonate in Modern Law

Separation of Powers in Australia

For an example of the separation of powers in action, please click here.

The Legal System

Law can be subdivided further into private and public law influenced by acts of parliament and the common law. Private law comprises a range of areas of law: tort law and employment or industrial law (which we will focus on in detail in this unit; employment law is a controversial inclusion under this category as it shares many aspects with the public law system of governance, especially compliance related to workplace, health and safety legislation). It also includes areas of law related to contract law, business law, commercial law and property law. Whereas, public law relates to criminal law, laws on taxation, administration such as welfare, education and healthcare and constitutional affairs. In short, if the matter is between individuals the matter is generally held to be private and governed by the civil system of law. In public law matters, like criminal law, it is the state’s responsibility to pursue a conviction or determine fault. For example, if you are assaulted, the police will take responsibility for criminal aspects of the assault. It is not left to the individual to pursue a conviction in the courts. However, this does not preclude a victim of crime from also making a claim against an alleged perpetrator in the civil system. As we will learn, assault and/or battery is a criminal offence, but it is also can be a civil matter as well, often described as trespass to the person. Another thing needing to mentioning is the burden of proof in the criminal justice system differs from the burden of proof in the civil justice system. To secure a conviction or successfully be awarded a claim in damages, the following burdens of proof apply:

- Criminal system – the burden of proof to secure conviction of a defendant accused of a crime is that it must be shown beyond all reasonable doubt that the defendant is guilty.

- Civil system – the burden of proof to be a successful in a claim of damages for a civil offence is that it must be demonstrated that, on the balance of probabilities, the defendant is guilty of doing or not doing something that the plaintiff or claimant claims they had agreed to do or not do.

We will revisit these concepts in chapter 2.

The Courts

The judicial system in Australia is divided into the civil courts and the criminal courts. Her In have focussed on court structure in Queensland and federal court only.

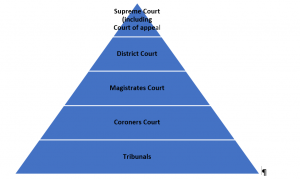

The Court System in Queensland

In Queensland there are additional courts and tribunals to the ones listed above and these are relevant to discussion in subsequent chapters. A total list of the courts in Queensland is as follows

- Supreme Court (Court of Appeal)

- Supreme Court (Trial Division)

- District Court

- Planning and Environment Court

- Land Appeal Court

- Land Court

- Magistrates Court

- Drug Court

- Coroners Court

- Childrens Court

- Mental Health Court

- Murri Court

- Domestic and Family Violence Specialist Court

- Tribunals

More information can be found here at Queensland courts and the Queensland Law Society.

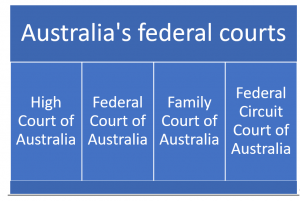

The Australian Federal Courts

The following is taken from the Attorney-General’s Department:

- “High Court of Australia

- is the highest court and the final court of appeal in Australia

- hears matters involving a dispute about the meaning of the Constitution, as well as final appeals in civil and criminal matters from all courts in Australia

- Federal Court of Australia

- hears matters on a range of different subject matter including bankruptcy, corporations, industrial relations, native title, taxation and trade practices laws, and hears appeals from decisions (except family law decisions) of the Federal Circuit Court

- Family Court of Australia

- is Australia’s specialist court dealing with family disputes, and hears appeals from decisions in family law matters of the Federal Circuit Court

- sits in each state and territory except Western Australia, where family law matters are heard by a state court, the Family Court of Western Australia

- Federal Circuit Court of Australia

- on 12 April 2013 the Federal Magistrates Court was renamed the Federal Circuit Court of Australia and the titles of ‘Chief Federal Magistrate’ and ‘Federal Magistrate’ changed to ‘Chief Judge’ and ‘Judge’ respectively

- the court hears less complex disputes in matters including family law and child support, administrative law, admiralty law, bankruptcy, copyright, human rights, industrial law, migration, privacy and trade practices.”[3]

The federal courts serve both public and private law and created by s 71 Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (Cth). Copies of the full act can be found here and here.

The Doctrine of Precedent

Keeping on the theme of the common law (or case law as it is often referred) I will explain a normative rule courts, based on the common law, follow. This is called the doctrine of precedent. Legal precedents must bind lower courts in the court hierarchy. It maintains predictability and prevents the judicial system from making capricious decisions. Otherwise anyone accessing the courts would be gambling on an outcome. Justice, if not predictable needs to stand to reason within the normative rules of justice. The doctrine imposes a binding precedent on the courts to follow decisions from previous court decisions. These decisions bind all lower courts when materially similar matters are brought before the courts. The law needs to provide certainty. Returning to the rule of law, individuals must be able to locate the law, in the case of common law judge made law, so it can be obeyed.

Precedent has both vertical and horizontal application. Vertical means that lower courts must follow the decisions of higher courts in cases that are materially similar and relate to the same or similar area of law. The same is said of courts that share the same hierarchy, this is horizontal application of precedent. Precedent does not prevent dissenting opinions from being heard. In fact, such judicial dictum may herald changes in the future and lead to overturning precedent based on overwhelming need that the law reflects the contemporary standards of the day. Precedent is either followed, applied or distinguished (not followed). Decisions made in previous court cases in subsequent cases that are materially and factually similar require that precedent is followed. When the courts look to previous decisions, adjudication of the facts determines whether the court to applies precedent from related cases. Finally, if the facts of a previous case are so dissimilar the decision made by the higher court is not followed and distinguished based on different facts that do not relate to the vertical or horizontal precedent. Courts must act consistently, but they must also be able to function with some flexibility. As we will find out next.

Why study law at all?

Some healthcare decisions are too big to be made either on your own or with the aid of your colleagues. Sometimes courts are needed to serve as the only objective practitioners that can resolve competing issues. Here’s a couple of examples:

It is never acceptable to murder a legal person in peacetime, right? Wrong. Tony Bland was the 96th and final victim of the Hillsborough disaster. Tony, injured on 15 April 1989, died a little under 4 years later. The injuries he suffered in 1989 led to Tony existing in a persistent vegetative state (PVS) or post-coma unresponsiveness (PCU). Tony was not on a life support machine; he was able to breath unaided. However, he was fed and hydrated artificially through a surgically inserted nasogastric tube. Tony’s condition had not improved since the incident. The medical team treating him, despite their efforts, concluded that there was no chance of recovery and this needed to be taken into consideration, alongside whether Tony was experiencing pain and suffering. A decision was made to discontinue artificial nutrition and hydration. This required an individual (HCP) to cease food and hydration as well as remove the nasogastric tube. This act would shorten Tony’s life and hasten his death. The proposed act fulfils, act and intention, to meet the criteria for homicide, and for the individual performing these acts to be charged with Tony’s murder. His treating team needed to find another way to let Tony to die that didn’t result in a life tariff being imposed on the person removing the nasogastric tube from Tony. The NHS Trust sought help from the courts. The case of Airedale NHS Trust v Bland [1993] 1 All ER 821 went to the United Kingdom’s highest court, then called the House of Lords before being renamed recently as the Supreme Court. What happened… all will be revealed in chapter 6.

Less than a decade later, the UK Court of Appeal was asked to intervene in the case of conjoined twins. The urgency of the cased meant that the House of Lords was unable to decide the outcome, and the decision was left with the United Kingdom’s second highest court, the Court of Appeal. Advances in surgery meant that one conjoined twin could survive but only at the expense of the life of her other conjoined twin. The courts, having no precedent to rely upon, aside from Bland, had to determine whether it was lawful one conjoined twin died to allow the other a prospect of living. The case of Re A (conjoined twins) [2001] 2 WLR 480 had to determine the lawfulness of killing one child to allow her sibling to live. Doing nothing would have resulted in both children dying. What were the judges to do, what indeed?

Final Word on the Introduction to CSB338