Chapter 3 Paramedic Professionalism

Stephen Bartlett

Chapter 3

Paramedic Professionalism

3.0 Introduction

I’m not going to lie, this is going to be a big chapter. There is a lot of ground to cover. So, here we go. Here’s what I hope to have shared with you by the end of the chapter:

- Definition of a profession

- Become aware of what is required to be professional

- Gain knowledge of guidance which can help inform professional practice

- Develop an introduction to responsibilities of professional practice

- Gain insight into various codes of conduct

- Develop a knowledge of what professionalism entails

- Medical negligence

- Duty of care

- Breach of duty

- Foreseeability

- Causation

- Damages

- Legal duty in relation to privacy and confidentiality – common law duty and duty under statute

- Relevant sections of legislation, so much legislation

- Exceptions to the duty to maintain confidentiality

- Consequences of breaching confidentiality

- Importance of good documentation

- Know what an employment contract is and be able to distinguish an employee from an independent contractor

- Possess an understanding of enterprise agreements and bargaining

- Know what workers compensation is

- Recognise issues and processes relating to termination of an employment contract

- Know what occupational health and safety is and how it relates to paramedic practice

- Be aware of issues relating to discrimination, bullying and harassment in the workplace

- Plus a few other things along the way

3.1 What is a profession?

Profession is a moot term. It is a construct. Defining a role as a profession makes it distinct from other roles. You could spend all day looking at and analysing a variety of attributes to describe a profession. I’ve just spent an hour, and it’s an hour I’ll not get back. Instead of trying to provide a history of defining a profession here, I’m going to do some epic copying, pasting and citing. Then it’s up to you to relate concepts of professionalism to paramedics and nursing.

Here’s an example of the criteria a profession must conform to from 1948:

- A profession must be full-time.

- Schools and curricula must be aimed specifically at teaching the basic ideas of the profession, and there must be a defined common body of knowledge.

- A profession must have a national professional association.

- A profession must have a certification program.

- A profession must have a code of ethics.[1]

Okay, don’t like that one? Here’s a definition for physicians; does this apply better?

“Profession: An occupation whose core element is work based upon the mastery of a complex body of knowledge and skills. It is a vocation in which knowledge of some department of science or learning or the practice of an art founded upon it is used in the service of others. Its members are governed by codes of ethics and profess a commitment to competence, integrity and morality, altruism, and the promotion of the public good within their domain. These commitments form the basis of a social contract between a profession and society, which in return grants the profession a monopoly over the use of its knowledge base, the right to considerable autonomy in practice and the privilege of self-regulation. Professions and their members are accountable to those served and to society”.[2]

Do you recognise yourselves here? For those of you who have undertaken placement, do you recognise your mentors here? Were paramedics and nurses always professional? If not, what’s changed? How do the professions ensure they remain current? To be a professional, an individual must be skilled in that particular art; it requires training to a high level that leads to proficiency. One thing that is agreed is that a profession must be bound by a code of conduct that is of service to society.

3.2 Healthcare professionals’ codes of conduct

The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) provide codes and guidelines for HCPs. Paramedics can be found here and nurses can be found here. All the codes published by AHPRA can be reduced to one concept: patient safety. Don’t get me wrong, I think it is a wonderful advancement for ambulance services to have their front-line services recognised on a professional register. It’s just that registration is less to do with you and more to do with the patients you treat. And, that is the way it should be. It’s important you are familiar with the code of conduct for the profession you plan to work. There are important concepts here you need to subscribe to and adapt into your practice as a matter of course. I have put the various codes on the CSB338 Blackboard page under the learning resources tab. I have included the code of conduct for midwives too. Who knows? You might deliver a baby or two in your time.

3.2.1 Avoiding “a bad day”

What did I learn from being a paramedic? Well, I learnt I can go without food, I learnt I can go without water. But sleep, I learnt, and so did my crewmates and my patients, I can’t go without. Sleep is my threshold. It’s my Room 101. It is the division between my coping and me turning into Leonard Smalls. The one thing I did not understand is that no matter how tired I became on shift, I always had just enough energy to be an arse. I considered anything longer than a blink to be a nap and would and could fall asleep absolutely anywhere, with stertor, lots of stertor. Thankfully petrol pumps have an automatic shutoff.

So how can you ensure that however you are feeling won’t impact the safety and wellbeing of patients. First thing is, you must recognise what makes you tick. What behaviour can you not abide in people? What flaws in your character do you possess that undermine your ability to overlook other people’s quarrelsome and vexatious behaviours? Once you have done that, you can develop strategies to help minimise unpleasant outcomes for you and your patient. It’s about taking ownership. Instead of complaining that you feel a certain way when person A does this or that. Change the perspective and acknowledge that you may feel in such and such a way when a person conducts themselves in a way you consider unappealing, but do not blame them for you feeling that way. That is what taking ownership is. Instead, identify that you feel unhappy, angry, belligerent or whatever it is when you encounter poor behaviour, but their behaviour is not responsible for you feeling that way. You are!

There are many variables on a given day that can affect our performance. Variables are a challenge. Variables are independent, several variables can turn up all at work and the collective overwhelming response to those variables can impact on your ability to care for your patients to the highest of standards. To engage in effective patient care, you need to, therefore, engage in effective self-care.

Think about this for a moment:

- 168 hours in a week

- o 36-48 hours spent at work each week

- 21%-28% approx.

- For those other 120-132 hours, what do I do?

- Eat

- Sleep

- Get to and from work

- Socialise

- o 36-48 hours spent at work each week

Self-care or self-preservation requires you to understand the impact shift work, diet, irregular sleeping pattern can have on you. You should also consider how your social life will be impacted. Consider, if you have friends who don’t work shifts and don’t work on Saturdays and Sundays, you will likely socialise with people who also undertake shift work: police, fire fighters, nurses, medics and other paramedics. Your new social group might not be the break from work to recharge you need.

Treating and caring for patients at 3am should not be any different from treating and caring patients at 3pm. Time of day may not even be a factor. If you have a propensity for acting the goat around patients, it’s probably more likely you will indulge in this type of (egregious) behaviour at 3pm than you will at 3am. At 3am, all you want to do is to get through your shift with the least fuss possible. Mistakes can happen at any time of the day, and they do. Attitudinal issues can happen at any time of the day too. And they do, too.

Now, I’d like you to visit the health and care professions tribunal service (HCPTS) page. It is the UK tribunal service – like AHPRA – is responsible for the health and care professions council fitness to practise hearings. Click on the link below:

https://www.hcpts-uk.org/hearings/search/

Select paramedic and click search. Hearings dating back 5 years are published. Select one that has detailed information recording the outcome of the fitness to practise hearing. It’s very easy to think that you will never undertake a course of action or omission that will lead to a fitness to practise hearing, but I would caution you against thinking like that. It’s important to be vigilant to acts or omissions that could lead to disciplinary investigation.

The Australian equivalent can be found here:

https://www.ahpra.gov.au/Publications/Tribunal-Decisions.aspx

We will spend time in tutorials discussing some of these cases. Plus, it forms the basis for your video essay.

You will be challenged working as a HCP, and there can be good challenges – like raising money for charity – and there can be bad challenges – like waiting for virology to get back to you after experiencing a needlestick injury. Placements should not be the only place you are exposed to these challenges. It is incumbent on universities to address challenges of this nature in paramedic and nursing learning outcomes. How, therefore, do we help prepare you in apprehension of becoming a victim? It is an odd notion to consider but nonetheless an important one. Developing and maintaining a healthy attitude to help navigate all challenges is a key feature of being a HCP. But how do we know we have one unless it’s tested. Furthermore, what is compassion fatigue and how do I prevent myself from getting it? The classroom doesn’t expose us to the true demands of being a HCP that can develop over time. Think of a piece elastic that gets stretched progressively over time. What do you think will happen when it reaches that moment of extreme tension?

The following sections detail the role of various agencies with responsibility for patient safety. It’s important I tell you about them. This approach favours the stick as oppose to the incentive to not engage in unprofessional conduct. If I am honest, I would rather focus on the consequence of taking care of your patients to the highest possible standard. Instead, I will tell you all the governmental and non-governmental bodies that will become involved when something goes awry. It’s all a bit Clockwork Orange but this method, despite this, will hopefully achieve my intended outcome. I’d much prefer the former approach, but, duty bound, the latter prevails, and a tale of sorrow awaits the people who do not conform to the standards of the profession.

Oh, and Twitter. Don’t get me started about Twitter. Stick in a Five and Go and let Jason from Sleaford Mods set you right about how the road to hell is paved with misguided tweets.

3.3 The National Law

On 1 December 2018 paramedics became recognised health professionals. Nurses have been a profession for much longer. AHPRA is a federal agency with jurisdiction in every state and territory and the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009 (Qld) enshrines the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Queensland) into Queensland’s legislature.

3.3.1 The role of the regulatory body

AHPRA determines whether an individual is suitable to become registered health professional. If an applicant is impaired their registration will not be approved:

impairment, in relation to a person, means the person has a physical or mental impairment, disability, condition or disorder (including substance abuse or dependence).[3]

The National Law also refers to professional misconduct. This relates to capability and fitness to practise. It is defined by the Act as:

- unprofessional conduct by the practitioner that amounts to conduct that is substantially below the standard reasonably expected of a registered health practitioner of an equivalent level of training or experience; and

- more than one instance of unprofessional conduct that, when considered together, amounts to conduct that is substantially below the standard reasonably expected of a registered health practitioner of an equivalent level of training or experience; and

- conduct of the practitioner, whether occurring in connection with the practice of the health practitioner’s profession or not, that is inconsistent with the practitioner being a fit and proper person to hold registration in the profession.

The Act defines unprofessional conduct as:

- professional conduct that is of a lesser standard than that which might reasonably be expected of the health practitioner by the public or the practitioner’s professional peers, and includes:

- (a) a contravention by the practitioner of this Law

- (b) the conviction of the practitioner for an offence under another Act, the nature of which may affect the practitioner’s suitability to continue to practise the profession

- (c) providing a person with health services of a kind that are excessive, unnecessary or otherwise not reasonably required for the person’s well-being

- (d) influencing, or attempting to influence, the conduct of another registered health practitioner in a way that may compromise patient care

- (e) accepting a benefit as inducement, consideration or reward for referring another person to a health service provider or recommending another person use or consult with a health service provider

- (f) offering or giving a person a benefit, consideration or reward in return for the person referring another person to the practitioner or recommending to another person that the person use a health service provided by the practitioner

- (g) referring a person to, or recommending that a person use or consult, another health service provider, health service or health product if the practitioner has a pecuniary interest in giving that referral or recommendation, unless the practitioner discloses the nature of that interest to the person before or at the time of giving the referral or recommendation.

Finally, the Act defines unsatisfactory professional performance. Unsatisfactory professional performance of a registered health practitioner means the knowledge, skill or judgment possessed, or care exercised by, the practitioner in the practice of the health profession in which the practitioner is registered is below the standard reasonably expected of a health practitioner of an equivalent level of training or experience.

The Act places an obligation on all registrants to report based on concerns about patient safety and the imposition of harm on patients by a registrant whose conduct, behaviour is suspected of being impaired. Mandatory reporting extends to students.

3.3.2 Mandatory reporting

Sections 139B-143 Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009 (Qld) details the requirements for mandatory notifications. I’m not going to provide a breakdown of the various sections, sub-sections and paragraphs as you can locate them easily. However, I will provide a line in relation to each section and relevant to mandatory reporting, so you are introduced to how far AHPRA casts its net to protect and uphold patient safety as a paramount concern:

- Section 140 – Definition of notifiable conduct

- (a) practising the practitioner’s profession while intoxicated by alcohol or drugs; or

- (b) engaging in sexual misconduct in connection with the practice of the practitioner’s profession; or

- (c) placing the public at risk of substantial harm in the practitioner’s practice of the profession because the practitioner has an impairment; or

- (d) placing the public at risk of harm by practising the profession in a way that constitutes a significant departure from accepted professional standards.

- Section 141 – Mandatory notifications by health practitioners other than treating practitioners

- Section 141A – Mandatory notifications by treating practitioners of sexual misconduct

- Section 141B – Mandatory notifications by treating practitioners of substantial risk of harm to public

- Section 142 – Mandatory notifications by employers

- Section 143 – Mandatory notifications by education providers

Section 86-90 Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009 (Qld) details the rules related to persons undertaking approved programs of study.

- (1) The National Board established for a health profession must decide whether persons who are undertaking an approved program of study for the health profession must be registered—

- (a) for the entire period during which the persons are enrolled in the approved program of study; or

- (b) for the period starting when the persons begin a particular part of the approved program of study and ending when the persons complete, or otherwise cease to be enrolled in, the program.

- (2) In deciding whether to register persons undertaking an approved program of study for the entire period of the program of study or only part of the period, the National Board must have regard to—

- (a) the likelihood that persons undertaking the approved program of study will, in the course of undertaking the program, have contact with members of the public; and

- (b) If it is likely that the persons undertaking the approved program of study will have contact with members of the public—

- (i) when in the approved program of study it is likely the persons will have contact with members of the public; and

- (ii) the potential risk that contact may pose to members of the public.

As you can see, AHPRA takes patient safety seriously. Perhaps there is another side to this venture, an undesirable side:

Fears mandatory reporting of doctors with mental health issues leading to suicides

What if mandatory reporting is counterproductive? What if there are HCPs experiencing challenges who are too afraid to seek help for fear of an AHPRA fitness to practise hearing? Is it not best in a fair and just society that HCPs are encouraged to seek help? This way patients remain safe because HCPs are seeking help for any issue they are experiencing. All of us are touched by the scourge of anxiety and depression in one way or another during our careers. Balancing patient safety with treating HCPs with care and respect needs to be considered. Many HCPs fear the involvement of the regulatory body and, anecdotally, with good reason. Are there other ways to ensure patient safety is upheld without derailing HCP’s careers entirely? Perhaps we need to look across the ditch and modify this system into one that upholds the safety of our patients and supports our HCPs in times when they need it most. Proponents of the current system argue this is what mandatory reporting does. Let’s have a chat about it in weeks 3 or 4 and maybe we can find out.

3.4 The Office of the Health Ombudsman in Queensland

According to the Office of the Health Ombudsman (OHO) website,[4] their purpose is to:

- Protect the health and safety of consumers

- Promote high standards in health service delivery

- Facilitate responsive complaint management

The OHO works under the Health Ombudsman Act 2013 (Qld) and in conjunction with the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law Act 2009 (Qld).[5] Section 11 Health Ombudsman Act 2013 (Qld) states the role and responsibility of the Health Ombudsman:

(1) The health ombudsman is responsible for receiving and dealing with health service complaints.

(2) The health ombudsman also deals with other matters, including investigating systemic issues in the health system.

The OHO website states that “complaints about health services are important, as they can identify areas for improvement, stop the same problems happening again and help to make health services better for all Queenslanders”.[6]

There aren’t any complaints published on AHPRA’s website about paramedics to date (12 August 2021), unlike the UK’s Health and Care Professions Tribunal Service. Do you think, before they became a registered health profession in Australia, patients treated by pre-registration paramedics were less safe? Do you think, when the QAS was responsible for investigating its own staff, it was a fair and unequivocal process. Do you think the new system of governing the profession is more equitable?

3.5 Public Sector Ethics

The Public Sector Ethics Act 1994 (Qld) resulted from the Fitzgerald Inquiry into possible illegal activities and associated police misconduct in result to corruption. The Public Sector Ethics Act 1994 (Qld) identifies four key principles fundamental to uphold the public good. These principles are found in sections 6-9 Public Sector Ethics Act 1994 (Qld):

- Integrity and Impartiality (section 6 Public Sector Ethics Act 1994 (Qld))

- (a) are committed to the highest ethical standards; and

- (b) accept and value their duty to provide advice which is objective, independent, apolitical and impartial; and

- (c) show respect towards all persons, including employees, clients and the general public; and

- (d) acknowledge the primacy of the public interest and undertake that any conflict of interest issue will be resolved or appropriately managed in favour of the public interest; and

- (e) are committed to honest, fair and respectful engagement with the community.

- Promoting the public good (section 7 Public Sector Ethics Act 1994 (Qld))

- (a) accept and value their duty to be responsive to both the requirements of government and to the public interest; and

- (b) accept and value their duty to engage the community in developing and effecting official public sector priorities, policies and decisions; and

- (c) accept and value their duty to manage public resources effectively, efficiently and economically; and

- (d) value and seek to achieve excellence in service delivery; and

- (e) value and seek to achieve enhanced integration of services to better service clients.

- Commitment to the system of government (section 8 Public Sector Ethics Act 1994 (Qld))

- (a) accept and value their duty to uphold the system of government and the laws of the State, the Commonwealth and local government; and

- (b) are committed to effecting official public sector priorities, policies and decisions professionally and impartially; and

- (c) (c)accept and value their duty to operate within the framework of Ministerial responsibility to government, the Parliament and the community.

- Accountability and transparency (section 9 Public Sector Ethics Act 1994 (Qld))

- (a) are committed to exercising proper diligence, care and attention; and

- (b) are committed to using public resources in an effective and accountable way; and

- (c) are committed to managing information as openly as practicable within the legal framework; and

- (d) value and seek to achieve high standards of public administration; and

- (e) value and seek to innovate and continuously improve performance; and

- (f) value and seek to operate within a framework of mutual obligation and shared responsibility between public service agencies, public sector entities and public officials.

A not uncommon feature of paramedic care is the moment when a patient or their relative shakes your hand and you feel the harsh crumple of a banknote when your respective palms meet. Something of value offered to you in the course of your work apart from your employment entitlements. From a Public Sector Ethics Act 1994 (Qld) perspective, the rule is not to accept or give gifts and benefits that affect, may be likely to affect or could be reasonably be perceived to affect the independent and impartial performance of your official duties. Several principles support public sector staff refusing gifts. These are:

- Signify the taking of a bribe

- Cause a perception of undue influence

- Provoke a sense of obligation

- Consciously or unconsciously influence decisions

- Compromise the independence, impartiality or good name of the organisation

The intention of the person offering the gift is immaterial. But, what about half price coffee, that’s okay, isn’t it? Not if you ask Frank Serpico, available to watch on SBS on Demand, (well, it was; it’s not now, I’ve just checked) it is. Might have to leave this one for tutorials.

3.6 Medical negligence

It all starts a little under 100 years ago with a young couple on a late summer evening in Paisley, Scotland and one/yin/wan bottle of ginger beer. Who knew? WHO KNEW? (Sorry about the shouting but ye’ll ken whit a mean in mo’.)

So, what is negligence? Negligence is causing harm to another because of a failure to exercise reasonable care. It is doing something that a reasonable person (paramedic/nurse) would not. Or not doing something that a reasonable person (paramedic) would do in like circumstances.

In the case of Blyth v Birmingham Water Works Co (1856) 11 Exch 781, judge Edward Alderson defined negligence at the same time as introducing the concept of the reasonable person into common law:

“Negligence is the omission to do something which a reasonable man, guided upon those considerations which ordinarily regulate the conduct of human affairs, would do, or doing something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do. The defendants might have been liable for negligence, if, unintentionally, they omitted to do that which a reasonable person would have done, or did that which a person taking reasonable precautions would not have done.”

The elements of negligence have been formed through common law principles (case/common law). These principles have been captured in legislation in all Australian states and territories following an extensive review of the common law reported in the Ipp Report.

A HCP has a duty to exercise reasonable care and skill in the performance of his or her professional duties:

“The duty is a single comprehensive duty covering all ways in which a (paramedic) may be called upon to exercise (his or her) skill and judgement”.[7]

The duty extends to responding to an incident; assessment and examination; interpretation of findings and diagnosis; treatment of the patient; extrication; transport; documentation and handover, all of which would be relevant to a case.

A wrongful act or omission committed by a paramedic performed during his or her duties may give rise to civil or criminal proceedings (gross negligence). Intention is not a requirement. Negligence is a civil wrong whereas gross negligence is a criminal law matter.

3.6.1 Elements of negligence

There are four elements needed to exist for negligence to be found:

- The existence of a duty of care;

- A breach of the standard of care;

- Damage suffered which was reasonably foreseeable, and;

- The breach caused, or materially contributed to the damage (causation).

Ambulance services and other health providers are treated differently to other emergency services. Ambulance services, from the perspective of policy. Have more in common with healthcare than they do police or fire. The following cases illustrate this point:

- Kent v Griffiths [2000] 2 All ER 474

- The ambulance service has a specific duty to respond to a particular emergency call

- Negligence may be found where an inadequate response makes the situation worse for the patient

- Hill v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire [1989] AC 53

- Does not confer generally immunity upon the police

- A duty of care would not arise without special circumstances

- Does not confer generally immunity upon the police

- The ambulance service has a specific duty to respond to a particular emergency call

If the four elements are not found, then the claim in negligence will fail. There must be a legal duty of care in existence. There is no common law duty to rescue another unless a duty of care exists to compel a person to rescue another.[8]

However, when we look at the Good Samaritan, we will learn that society does not want to discourage people from helping others. Furthermore, the case of Lowns v Woods (1996) Aust Torts Reports 81-376 contrasts with this view and holds that despite there not being a relationship between a doctor and an unwell person, the courts will regard failure to provide aid as an example of unsatisfactory professional conduct.

3.6.1.1 Duty of care

We’ve already discussed the concept of health law as a distinct legal discipline. Forgive me for a moment because we are going to go a little op-ed briefly. The evolution of medical law stems from the case of Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] 1 WLR 582. Generally, the medical fraternity (and I use that term deliberately) may have been reluctant to entertain or even indulge legal action based on the patriarchal view that people are fortunate to receive the help they do, and they should be jolly well grateful. Litigation in medical practice is worthy of its own text. And I don’t wish to add too much to this particular treatise. Except, things go wrong in healthcare, it’s not always intended, people do suffer losses and based on those losses encounter challenges that financial recompense can repair.

How did it all begin? Well, it all began with a patient not being secured to a gurney while undergoing electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). In the case of Bolam it was asked, extending Lord Atkin’s concept of reasonableness:

“How do you test whether an act or failure is negligent? In an ordinary case it is generally said you judge it by the action of the man in the street …. by the conduct of the man on the top of a Clapham omnibus”.[9]

When involved in a situation, which involves the use of some special skill or competence (such as a doctor, nurse or paramedic), then the test is the standard of the ordinary skilled (doctor or nurse, or paramedic) person exercising and professing to have that special skill. A person need not possess the highest expert skill; it is well established law that it is enough if he exercises ordinary skill of an ordinary competent man exercising that particular art. The test is determined by the following:

The defendant is not guilty of negligence if he acted in accordance with a practice accepted as proper by a responsible body of medical men skilled in a particular art.

Further supporting the framework of self-regulatory governance, the case of Sidaway v. Governors of Bethlem Royal Hospital held:

“In short, the law imposes the duty of care; but the standard of care is a matter of medical judgement”.[10]

In the case of Bolitho v. City and Hackney Health Authority [1996] 4 All ER 771, the courts revisited the Bolam principle. The House of Lords, the UK’s supreme court, introduced the concept of logical analysis. The courts are prepared to accept the Bolam principle, but the courts reserve the right to determine the adequacy of the justification of an act or omission based on the premise of logical analysis. If the justification for doing something or not doing something does not stand up to logical analysis then no matter the number of medical personals that support the act or omission, the courts may determine that the HCP was negligent in their act or omission.

Hopefully by now, you will be familiar with the case of Masson. Despite on what is considered good, reasonable or even evidence-based disputes based on accepted practice are rife in healthcare.

“The trial judge was satisfied that, in 2002, “the practising medical profession traditionally regarded adrenaline as the ordinarily preferred drug to administer to asthmatics in extremis.” But, in the present day, his Honour said, whilst there was a “credible body of medical practitioners” who remained of that view, there was a similar body “who regard salbutamol as an at least equally preferable drug”. Whilst there were “credible views in 2002 favouring the equivalent utility of salbutamol”, there was not what his Honour described as a “credible body” of professional opinion to that effect”.[11]

I hope we can discuss this in more detail in tutorials but, goodness gracious, what does that even mean. Talk about weasel words. Anyway, I don’t want to take you away from you making your own minds about the Masson cases. Read them – you should be able to find all the cases on the CSB338 Learning Management System page (Blackboard or Canvas – depends what year you’re reading this. I will have probably forgotten to update so all of this is really a waiver and I’m future proofing this part from unhappy feedback) – think about them and let me know what you think.

3.6.1.2 Standard of care

Returning to the elements of negligence, once a duty has been established it needs to be determined whether a person was in breach of that duty. Section 22(1) Civil Liability Act 2003 (Qld) (CLA) states:

A professional does not breach a duty arising from the provision of a professional service if it is established that the professional acted in a way that (at the time the service was provided) was widely accepted by peer professional opinion by a significant number of respected practitioners in the field as competent professional practice.

Sub-section 2 of s 22 CLA reinforces the common law principle drawn for Bolitho:

However, peer professional opinion cannot be relied on for the purposes of this section if the court considers the opinion irrational or contrary to a written law.

The CLA limits the absolutist approach of Bolam by stating in sub sections (3) and (4):

The fact that there are differing peer professional opinions widely accepted by a significant number of respected practitioners in the field concerning a matter does not prevent any one or more (or all) of the opinions being relied on for the purposes of this section.

Peer professional opinion does not have to be universally accepted to be considered widely accepted.

Where do paramedics obtain their standards from. Here are some suggestions:

- Statutory provisions imposing a standard of care.

- Professional Codes of Practice / Code of Conduct.

- Employer policies and procedural guidelines i.e. QAS Clinical Practice Manual (CPM).

- Peer professional opinion.

Here’s a list of examples of areas in which a paramedic could be called upon to exercise his/her skill and judgement, and any failure may result in a claim of negligence:

- Response to a request for assistance

- Location of the scene and patient at the scene

- Assessment (clinical; scene; VIRCA – more on this in upcoming chapters – if relevant) and interpretation/diagnosis

- Carrying out of various procedures (clinical and others)

- Scene management – protection of others

- Administration of prescribed medications

- Patient supervision and employment of safety measures

- Providing advice

- Extrication and transportation

- Handover or conveying relevant information in a timely manner.

Now, this is not exhaustive list, but it does provide examples of where the wheels might come off in terms of paramedic or other similar types of healthcare (ED nursing). I don’t include this to cause you to doubt your chosen career path. I include them here because I believe the value and importance of being informed. Forewarned is forearmed. It is important to relate this to common issues arising in the delivery of out-of-hospital care. In the case of Kent v. Griffiths & Ors [2000] EWCA Civ 25 the facts of the case were:

“The ambulance did not reach the claimant’s home within a reasonable time. It could and should have arrived at the claimant’s home at least 14 minutes sooner than it did. If it had arrived in a reasonable time, as it should have done, there was a high probability that the respiratory arrest, from which the claimant suffered, would have been averted”.[12]

The Court of Appeal judges found:

“There is no reason why there should not be liability (in negligence) if the arrival of the ambulance was delayed for no good reason. The acceptance of the call (in this case) established the duty of care. It was the delay which caused the further injuries”.[13]

Furthermore, a claim in negligence could arise in the event reasonable steps are not taken to:

- Locate a patient;

- Failure to assess adequately;

- The failure of a health care provider to conduct a proper examination, in circumstances where the patient’s clinical presentation would indicate the need to conduct such an examination, would amount to a breach of the duty of care owed and may result in negligence.

- Failure to treat a patient;

- The failure of a health care provider to exercise due care when providing patient treatment would amount to a breach of a duty of care and may give rise to an action in negligence.

- Failure to transport a patient, and;

- The failure to seek medical assistance (transport to hospital) result in negligence if the patient suffers further harm which could have been prevented.[14]

- Failure to document.

- Failure to adequately document patient assessment and treatment details

- Failure to ensure that documented assessment and treatment details are left in the appropriate location, would amount to a breach of the duty of care owed, and may result in negligence.[15]

It’s not just about the individual either see the case of State of Queensland v Roane-Spray [2017] QCA 245.

3.6.1.3 Damages

A person must suffer a loss as a resultant of another’s act or omission where a duty of care has been established at law. The loss must be related to:

- Physical injury

- Psychological injury (recognisable psychiatric condition)

- Financial loss (i.e. a dependent)

Tony Bland was the final person to die from injuries sustained at the Hillsborough stadium football disaster on Saturday 15 April 1989. Many friend and families suffered losses resulting from the events of that day. To understand remoteness a bit better, Hillsborough offers us an additional insight. Many people who were at the stadium watching the disaster unfold sustained psychological injury but not physical injury. The match was tele-cast live and there were people at home, knowing their friends and family were at the stadium who watched on as people were crushed. People watching at home claimed they suffered a loss based on psychological injury while watching the events on television. Their failed in their claim. The courts held they were too remote to suffer injury based on watching events unfold on television. This provides us with a better understanding of what the courts are prepared to accept as causing psychological harm. Proximity appears to be a criterion.

3.6.1.4 Causation

One of my all-time favourite lawyers is H.L.A. Hart. He wrote the best book on causation in the English language. I am going to try best to distill that incredible work in a paragraph of two. I will fail. Nevertheless, and undeterred here is my punctuated appreciation of causation.

The injured plaintiff must show that the loss or damage suffered was caused by the act or omission (breach of duty), or that the breach of duty materially contributed to the loss or damage.

Now, here’s where I introduce the ‘but for’ test or principle. The ‘but for’ principle is grounded in Scooby-Doo.

I would have gotten away with it weren’t it but for you pesky kids.

Its concept is all the more beautiful for its simplicity. However, its application is another matter entirely.

In the case of Barnett v. Chelsea and Kensington Hospital Management Committee [1969] 1 QB 428, a group of men arrived at an accident and emergency department complaining of abdominal pain. The matron in charge called for the doctor who failed to respond. All the men died. Was the doctor negligent? No, he wasn’t. Based on the ‘but for’ principle the men would have died even had the doctor attended. They had all been poisoned with arsenic. At the time there was no known antidote for arsenic poisoning. And there you go, the ‘but for’ principle in a nutshell.

How does the ‘but for’ principle relate to causation? It is the break in the chain of causation. In the case of R v Cheshire [1991] 1 WLR 844, which is my favourite chip shop homicide case of all time, it was stated:

“Even though negligence in the treatment of the victim was the immediate cause of his death, the jury should not regard it as excluding the responsibility of the defendant unless the negligent treatment was so independent of his acts, and in itself so potent in causing death, that they regard the contribution made by his acts as insignificant”.[16]

Section 11 Civil Liability 2003 (Qld) states:

(1) A decision that a breach of duty caused particular harm comprises the following elements—

(a) the breach of duty was a necessary condition of the occurrence of the harm (factual causation);

(b) it is appropriate for the scope of the liability of the person in breach to extend to the harm so caused (scope of liability).

(2) In deciding in an exceptional case, in accordance with established principles, whether a breach of duty—being a breach of duty that is established but which cannot be established as satisfying subsection (1)(a)—should be accepted as satisfying subsection (1)(a), the court is to consider (among other relevant things) whether or not and why responsibility for the harm should be imposed on the party in breach.

(3) If it is relevant to deciding factual causation to decide what the person who suffered harm would have done if the person who was in breach of the duty had not been so in breach—

(a) the matter is to be decided subjectively in the light of all relevant circumstances, subject to paragraph (b); and

(b) any statement made by the person after suffering the harm about what he or she would have done is inadmissible except to the extent (if any) that the statement is against his or her interest.

(4) For the purpose of deciding the scope of liability, the court is to consider (among other relevant things) whether or not and why responsibility for the harm should be imposed on the party who was in breach of the duty.

I know, I know, you don’t like reading legislation, it’s boring. It can be boring, but it can be helpful, too. And that’s why I include it here. But what does it mean for all you nascent HCPs? It’s an oldie and a goodie:

“The law imposes (upon a health provider) a duty to exercise reasonable care and skill in the provision of professional advice and treatment. That duty is a single comprehensive duty covering all ways in which (the health provider) may be called upon to exercise his/her skill and judgement”.[17]

Here’s a list of examples of areas in which a paramedic could be called upon to exercise his/her skill and judgement, and any failure may result in a claim of negligence:

- Response to a request for assistance

- Location of the scene and patient at the scene

- Assessment (clinical; scene; VIRCA if relevant) and interpretation/diagnosis

- Carrying out of various procedures (clinical and others)

- Scene management – protection of others

- Administration of prescribed medications

- Patient supervision and employment of safety measures

- Providing advice

- Extrication and transportation

- Handover or conveying relevant information in a timely manner.

Now, this is not exhaustive list, but it does provide examples of where the wheels might come off in terms of paramedic care. I don’t include this to cause you to doubt your chosen career path. I include them here because I believe the value and importance of being informed. Forewarned is forearmed.

3.7 The Good Samaritan

One question I am asked a lot. Even more than, why didn’t you give me a 7? Is what do I do as a student HCP if I witness someone collapse in front of me. The only answer is: *Act Reasonably*. You don’t want to do anything wrong; I get that. You want to help; I get that, too. You must ACT REASONABLY, however. It’s easy to get caught up in the moment and pitfalls wait for us those of us who act in haste and strive to think clearly under pressure. We’ll chat more about it in tutorials, I promise.

The two key pieces of legislation in Queensland that guide us are the Civil Liability Act 2003 (Qld) and the Law Reform Act 1995 (Qld). Section 26 Civil Liability Act 2003 (Qld) states:

- Protection of persons performing duties for entities to enhance public safety

-

- (1) Civil liability does not attach to a person in relation to an act done or omitted in the course of rendering first aid or other aid or assistance to a person in distress if—

- (a) the first aid or other aid or assistance is given by the person while performing duties to enhance public safety for an entity prescribed under a regulation that provides services to enhance public safety; and

- (b) the first aid or other aid or assistance is given in circumstances of emergency; and

- (c) the act is done or omitted in good faith and without reckless disregard for the safety of the person in distress or someone else.

- (2) Subsection (1) does not limit or affect the Law Reform Act 1995, part 5.

- (1) Civil liability does not attach to a person in relation to an act done or omitted in the course of rendering first aid or other aid or assistance to a person in distress if—

Section 16 Law Reform Act 1995 (Qld) states:

Liability at law shall not attach to a medical practitioner, nurse or other person prescribed under a regulation in respect of an act done or omitted in the course of rendering medical care, aid or assistance to an injured person in circumstances of emergency—

(a) at or near the scene of the incident or other occurrence constituting the emergency; or

(b) while the injured person is being transported from the scene of the incident or other occurrence constituting the emergency to a hospital or other place at which adequate medical care is available;

if—

(c) the act is done or omitted in good faith and without gross negligence; and

(d) the services are performed without fee or reward or expectation of fee or reward.

There you have it, how Queensland sees its Good Samaritans. No-one wants to discourage people from helping other people. What the law addresses is the need to act within our limitations and to respond reasonably. You should only be fearful of litigation if you act egregiously. Otherwise, respond within your limitations. Be honest with others about your status and don’t engage in an act or omission that will lead to further harm.

My final word on negligence, if you are still unclear on this topic, is watch Dirty Dancing. Everything you need to know about acting and behaving reasonably is contained in this film. What it can’t teach you isn’t worth knowing. It’s this simple: let Baby and Dr Houseman show you the way.

3.8 Privacy and Confidentiality

It’s entirely up to yourselves if you want to tell social media the make and model of your first car, your first pet’s name, the colour of the pushbike you had when you were 10, and so on. That’s part of your private life. It’s not really confidential information. Driving around in your ‘74 Monaro, people would have seen you. You would have had to share this information with your insurer, government departments responsible for roads and transport. How can that be private? It can’t. However, there is pile of information that is private and confidential to you and you get to decide who gets to know about it and who doesn’t. Remember, that time when you were fifteen and someone suggested it would be a great idea if you… Okay, maybe here is not the place.

3.8.1 Confidentiality

According to section 139 Hospital and Health Boards Act 2011 (Qld) confidential information means information, acquired by a person in the person’s capacity as a designated person, from which a person who is receiving or has received a public sector health service could be identified. Privacy and confidentiality are sometime used interchangeably but it is accurate to discuss them separately.

Section 25(a) Human Rights Act 2019 (Qld) tell us a person has the right to have their privacy, family, home or correspondence free from unlawful or arbitrary interference. A person has, to a limited extent, a private life. The same cannot be said for confidentiality. Confidentiality is breached all the time. What’s important is it must be done so lawfully or with our consent.

Despite that privacy and confidentiality are used interchangeably and I have called this section privacy and confidentiality, I will be talking more to confidentiality than to privacy here before talking to privacy in relation to patient documentation. There’s, as I am sure you suspect, lots and lots of legislation and a bit of common law in this space, and quite a lot of duplication.

Confidential information is pretty much any information disclosed in the health professional-patient relationship. If a patient has shared, divulged or you have observed anything in the context of the course of your work as a HCP it is a safe assumption to make that this is confidential information. Personal information given in the course of the healthcare relationship, e.g. patient’s name, nature of the illness, diagnosis and treatment given should be regarded as information given in confidence. Why the big deal? In a world of Embarrassing Bodies and people sharing in utero ultrasound scans on social media to announce a pregnancy people seem to be screaming ostensible confidential and personal information from the rooftops. Here’s why it is important:

- Patients divulge highly sensitive information to healthcare professionals with the expectation that such information will not normally be disclosed without their consent.

- Disclosures are made to a healthcare professional on the basis that the information will remain confidential.

- Establishes trust and encourages patients to talk openly about private and sensitive matters that may be relevant to a diagnosis i.e.: sexual activity; alcohol consumption; drug use; or mental illness.

- If confidentiality not guaranteed, people may not seek treatment and, in some cases, this could have impact on health of community i.e.: infectious diseases.

- It protects patients; fundamental rights to privacy and dignity.[18]

Queensland has legislation that requires health professionals to not disclose confidential information unless permitted by legislation or the common law. The case of Trevorrow v South Australia (2006) 94 SASR 64 states that the HCP-patient relationship gives rise to a legal duty of confidentiality, as information of a confidential nature is disclosed by patients with an expectation that it will be kept confidential. Patient consent does not need to be express, it can be implied.[19]

Like treating a red light like a given way when driving under emergency conditions, there are some exemptions and exceptions to upholding patient confidentiality. Imagine if you have been dispatched to a cardiac arrest and you went through and set off four red light cameras en route and received cumulative fines and demerit points for each of them. Doesn’t make sense, right? Under lawful directives you need protection. Same goes for disclosing confidential information; a healthcare provider will be protected from an action for breach of confidence where a statute requires or permits disclosure.

This is a bold claim but one I will make, nonetheless. Many of you, since starting the Pressbook, will have discovered a hitherto unexplored love of all things legislative. You’re welcome. Don’t get too carried away in your appreciation quite yet. Like those adverts that tell you to hold on before you commit to a purchase because they are prepared to offer you more, SO MUCH MORE. I’m going to provide you with, not one, but two pieces of legislation to slake your thirst for all things legislative:

- Hospital and Health Boards Act 2011 (Qld)

- Disclosure required or permitted by law (s143)

- When records required for purposes of legal proceedings arising out of health legislation: pursuant to court order

- Consent of the patient to disclosure (s144)

- Disclosure for care and treatment of patients (s145)

- Sharing information amongst treating team for purposes of organising best nursing care

- Discussing patient with nurse who will take over after your shift

- Disclosure to person with sufficient interest in health and welfare of patient (s146)

- Spouse, parent or child of the patient

- Friend who has a close personal relationship with the person

- Will not apply if patient specifically asks that the confidential information not be disclosed generally or to that person (s 146(3))

- Disclosure to lessen or prevent serious risk to life, health or public safety (s147)

- Disclosure for protection, safety or wellbeing of a child (s148) (e. mandatory reporting of suspected child abuse)

- Disclosure for funding arrangements and public health monitoring (s149)

- Disclosure for purposes related to health services (s150)

- Disclosure to or by inspector (s152)

- Disclosure to Act officials (s153)

- Disclosure to or by relevant chief executive (s154)

- Disclosure to health practitioner registration board (s155)

- Disclosure to health ombudsman (s156)

- Disclosure to person performing functions under Coroners Act 2003(Qld) (s157)

- Disclosure to lawyers (s158)

- Disclosure to Australian Red Cross Society (s159)

- Disclosure of confidential information in the public interest (s160)

- Public interest disclosure involves cases where, in order to protect the public, the health practitioner or authority releases confidential information about the patient to police or other authority.

- The decided cases clearly establish that the law recognises an important public interest in maintaining professional duties of confidence but the law treats such duties not as absolute, but as liable to be overridden when there is held to be a stronger public interest in disclosure.[20]

- W v Edgell [1990] All ER 385 – we will revisit this case in chapter 7 bit I will discuss the concept of public interest below briefly

- Disclosure for purpose of Health Transparency Act 2019 (s160B)

- Necessary or incidental disclosure (s161)

- Disclosure required or permitted by law (s143)

- Ambulance Service Act 1991 (Qld)

- Disclosure required or permitted by law (s50E)

- Disclosure with consent (s50F)

- The disclosure is authorised if another person who is authorised to consent on the patient’s behalf consents to the disclosure

- Person who is authorised to consent on behalf of a patient — a parent or guardian

- Disclosure to a person who has sufficient interest in the health and welfare of the person (s50G)

- The person’s child, guardian, parent or spouse

- An adult who is providing home care to the person because of a chronic condition or disability

- A medical practitioner who has had responsibility for the care and treatment of the person

- Disclosure of confidential information for care or treatment of the person (s50H)

- Disclosure is general condition of person (50I)

- Example of communicated in general terms—

- A service officer discloses that a person’s condition is “satisfactory”.

- Disclosure to police or corrective services officers (s50J)

- Disclosure for administering, monitoring or enforcing compliance with Act (s50K)

- Disclosure to Commonwealth, another State or Commonwealth or State entity (s50L)

- Disclosure to health ombudsman (s50M)

- Disclosure to Australian Red Cross (s50N)

- Disclosure to person performing function under Coroners Act 2003 (Qld) (s50O)

- Disclosure is authorised by chief executive (s50P)

- Necessary or incidental disclosure (s50Q)

- The disclosure of confidential information to support staff at a public sector hospital who make appointments for patients, maintain patient records and undertake other administrative tasks

- The disclosure of confidential information to advise the chief executive about authorising the disclosure of confidential information under section 50P

- Accessing contact details for a person to seek the person’s consent under section 50F to the disclosure of confidential information

- Application of this division to former designated officers (s50R)

- Even if you leave the QAS, you are bound by confidentiality laws

- Disclosure to health practitioner registration board (s50S)

- Example of communicated in general terms—

- The disclosure is authorised if another person who is authorised to consent on the patient’s behalf consents to the disclosure

It’s fairly comprehensive, isn’t it? Where might you think you could fall foul of the legislation? Based on the journalistic premise that if it bleeds, it leads; let’s imagine, for a moment, you are dispatched to a stand-by or rendezvous point. Maybe it’s a house fire with persons reported but unconfirmed. You stand like a coiled spring festooned in hi-vis and PPE, waiting to be called into action by fire or police, or even both. A smart looking individual approaches you and strikes up a conversation. They ask how your day has been, remarks how marvellous you are, maybe they stand there and applaud. All you can offer is a blush and a mumbled response. Then they ask you what’s going on. And because you don’t wish to appear rude, you tell them. And you tell them in way more detail than you should because you wish to develop community relations. Without ever making a concerted effort to do so or even meaning to, you become a spokesperson for the ambulance service. Remain alert to patient confidentiality. Incidental disclosure is covered by legislation but only in limited circumstances. However, there are also times where it is incumbent upon you to disclose confidential information.

Not only are there statutory provisions permitting disclosure, there are statutory provisions requiring disclosure. Sections 67-88 Public Health Act 2005 (Qld) is responsible for governing when notifiable and usually communicable conditions are to be divulged. For example, see sections 70 and 71 Public Health Act 2005 (Qld):

70 When a doctor must notify

(1) A doctor must, under subsection (2), notify the chief executive if an examination of a person by the doctor indicates that the person—

(a) has or had a clinical diagnosis notifiable condition; or

(b) has or had a provisional diagnosis notifiable condition.

71 When the person in charge of hospital must notify

(1) A person in charge of a hospital must, under subsection (2), unless the person in charge has a reasonable excuse, notify the chief executive if an examination of a person by a doctor in the hospital indicates the person—

(a) has or had a clinical diagnosis notifiable condition; or

(b) has or had a provisional diagnosis notifiable condition.

If you would like to know more about notifiable conditions in Queensland please visit the Queensland Health and Department of Agriculture and Fisheries:

- https://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical-practice/guidelines-procedures/diseases-infection/notifiable-conditions/list

- https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/business-priorities/biosecurity/animal-biosecurity-welfare/animal-health-pests-diseases/notifiable

In addition to the Public Health Act 2005 (Qld), the Child Protection Act 1999 (Qld) sets out legal provisions for the lawful breach of confidentiality based on:

13A Action by persons generally

(1) Any person may inform the chief executive if the person reasonably suspects—

(a) a child may be in need of protection; or

(b) an unborn child may be in need of protection after he or she is born.

(2) The information given may include anything the person considers relevant to the person’s suspicion.

13E Mandatory reporting by persons engaged in particular work

(1) This section applies to a person (a relevant person) who is any of the following —

(a) a doctor;

(b) a registered nurse.

The following section provides for protection from liability following a breach of confidential information based on the reasonable held belief a child’s health and wellbeing is at risk of (significant) harm:

197A Protection from liability for giving information about alleged harm or risk of harm

(1) This section applies if a person, acting honestly and reasonably—

(a) gives information to the chief executive under chapter 2, part 1AA; or

(b) otherwise notifies the chief executive or another public service employee employed in the department that the person suspects—

(i) a child has suffered harm, is suffering harm or is at risk of suffering harm; or

(ii) an unborn child may be at risk of harm after he or she is born.

In section 2.5.1, I told you about court appearance. Here is another occasion where you will be permitted to breach the confidentiality of another. Disclosure is not in breach if made pursuant to a court order i.e. subpoena or notice to appear and give evidence and/or to deliver documents containing confidential information. Disclosure is not in breach if disclosed during the pre-trial phase pursuant to the rule of discovery i.e. handing over all documents that relate to the legal proceedings including those which contain information that would otherwise be confidential.

3.8.1.1 Public interest disclosure

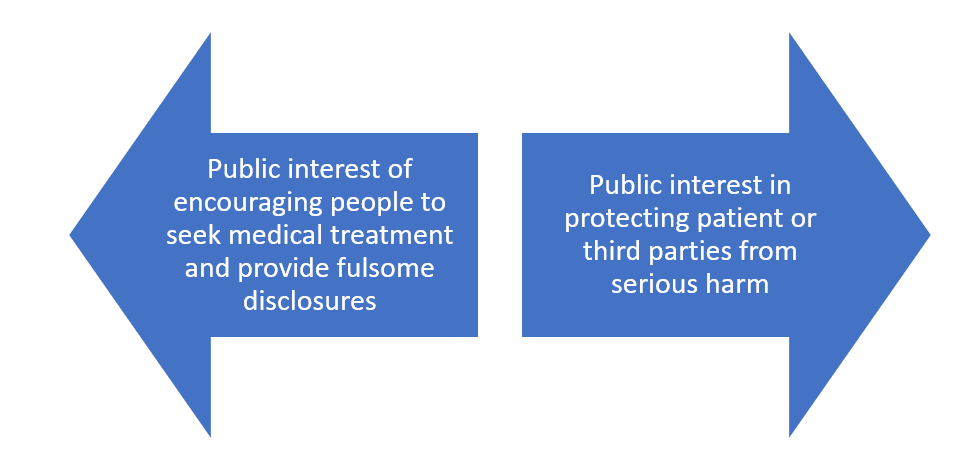

Keen eyed observers of the table of contents will see that there are two sections on public interest disclosure (PID) in this chapter. This is deliberate as I need to visit PIDs in the setting of whistleblowing too. First, here is the section on the justification of PIDs and the exception to the duty to maintain confidentiality. PIDs are made on the balance of factors:

Whether a disclosure based on the public interest is justified is a difficult issue to assess and answer. There will need to be real and foreseeable elements to help determine the decision to disclose into the public space certain confidential information. This might be urgency: an impending or immediate danger. This would only be used to authorise disclosure to relevant authority in order to prevent or minimise risk of danger. A decision to breach patient confidentiality needs to also be balanced against the risk of:

- Breach of Hospital and Health Boards Act 2011 (Qld) results in an offence being committed (fine or possibly jail time)

- Healthcare providers may also be sued in the civil courts by patients for breach of confidentiality

- Damages may be awarded to the patient for any injury or harm caused by a breach of confidentiality

- A health professional who breaches a patient’s confidence may be guilty of professional misconduct

- A breach of the ethical rules set out in Code of Ethics & Code of Conduct may lead to disciplinary action being commenced against the health care professional

To understand the justification for PIDs in a healthcare context better we need to revisit our old friend utilitarianism:

The justification for upholding patient confidentiality is overshadowed by the justification for breaching patient confidentiality. Confidentiality can only be breached based on the principle that the risk of not doing so is proportionate to the risk of harm occurring. If we don’t uphold patient confidentiality this could impact help seeking behaviours. This speaks in part to the mandatory reporting of HCPs to the regulatory body and on some of the controversy that underpins mandatory reporting. Ultimately, the primacy of confidentiality in healthcare promotes patients presentating for treatment and making full disclosure of relevant information. It enables effective medical treatment to be provided to members of a community and containment of illness and disease in society. It upholds faith in the system. I’m going to leave the final words to the court in X v Y [1988] 2 All ER 648:

In the long run, preservation of confidentiality is the only way of securing public health; otherwise doctors will be discredited as source of education, for future individual patients will not come forward if doctors are going to squeal on them. Consequently, confidentiality is vital to secure public as well as private health, for unless those infected come forward they cannot be counselled and self-treatment does not provide the best care … If people felt that there was any chance of information given to their doctor, or the doctor’s diagnosis, being passed on, people would be reluctant to seek advice and the disease would go underground. Confidentiality must be absolute or almost absolute.

How are you feeling at this point? You will be wondering how many of these sections will you need to memorise. The answer is simple: all of them. No, not really. I know there is a lot of information here, but it is important you leave this section with a broad understanding of upholding confidentiality in the context of professionalism. You are entitled to share patient information but only where it is justified by law. Otherwise, you are bound to uphold and maintain patient confidentiality. There will be times you will be uncertain, and some people can be persuasive if they want to obtain information from you, but your duty is to your patient. If you are uncertain, ask. A consult line is a wonderful thing. Use it.

3.8.2 Privacy and patient documentation

What? You mean we haven’t even got onto documentation? Yup, that’s right. There’s still a way to go. Personal information and privacy go together like hand in glove. Reasons for protecting individual right to privacy are numerous. They can include protection from unwarranted interference, illegally obtaining personal details to commit fraud, uphold and protect reputation, have personal information used for unintended purposes. Here are some example of private information:

- Personal details

- Name

- Gender

- Address

- Date of birth

- Email address

- Drivers licence number

- Physical characteristics

- Sensitive information

- Political beliefs

- Religious beliefs

- Medical records

- Prescription medication records

- Disability status

- Employment information

- Human Resource records

- Superannuation statements

- Tax status

- Pre-tax adjustments

Of course, there is going to be legislation that operates in this area. Statutes exist at both a state and federal level.

- Privacy Act 1988 (Cth)

- Creates 11 Information Privacy Principles (IPPs) which apply to the Commonwealth public sector and have been extended to apply to the private sector in the form of National Privacy Principles (NPPs)

- Information Privacy Act 2009 (Qld)

- Adopts the IPPs (for public sector agencies) and NPPs (for Queensland Health)

Section 12 Information Privacy Act 2009 (Qld) describes personal information:

Personal information is information or an opinion, including information or an opinion forming part of a database, whether true or not, and whether recorded in a material form or not, about an individual whose identity is apparent, or can reasonably be ascertained, from the information or opinion.

Paramedics can reveal all kinds of personal information inadvertently. Your phone is recording where you are all the time, often under the guise of health data. It lets you know what the weather for the suburb you are in without you having to do anything. It tells you how many steps you’ve walked, how many calories you’ve burnt. Ask your phone something and who knows, the next time you open social media you might see some adverts related to some inane or innocuous question you asked one of the many digital assistants available on the market.

HCPs record sensitive information all the time. You do it so often that you probably forget the privilege you have obtaining access to this type information. Patient records serve several functions:

- Provide a historical account of a patient’s health care experience

- With the consent of the patient, a patient’s records may be used for teaching, quality and research purposes

- Relevant records may be subpoenaed and used in civil and criminal proceedings

In a civil action records may be used to either prove or refute a claim of negligence on the part of health carers or be used in an action against a health care facility. In criminal proceedings, a patient’s records may be used as evidence to support a complaint of assault or provide evidence that an injury occurred & show nature and extent of injury.

When you record something on a patient’s record you have to understand it won’t be your intended audience who will read the patient record. You might think that only other HCPs will read it, or paramedics auditing your paperwork will read it. Anyone with a vested interest in the documentation may be granted access to it. This could include the patient, lawyers, insurers to name only a few. When you document something, make sure that you consider the unintended audience. This can prevent you from feeling professionally embarrassed or even have your professional conduct called into question.

*Look, this bit is important*

*Please read*

↓

When you document something, the criteria you must achieve is everything you write or communicate is accurate, objective and true. Work from the premise that if you didn’t write it down, it didn’t happen. Furthermore, if it didn’t happen or you didn’t observe it then do not write it down, ever. This means if the patient’s respiratory rate is 14, this is based on you counting it, not looking up, glancing at the patient and then writing down 14 for respiratory rate. You will get away with it for so long and then you won’t. This conduct and conduct like this can form part of a fitness to practise hearing and then you will wish you had put your hand on the patient’s chest, looked at your watch and counted the respiratory rate accurately. Don’t be slack. Always, and I mean always offer gifts to your future self. Doing things right the first time is a way of being good to a future version of you, who will only have to shoulder the burden of having to deal with it if you don’t do it right and they will be angry at you, so angry.

A good way to think about documentation is documentation has its own set of ABCs:

- Accuracy

- Brevity

- Clarity

You must add truthfulness to this. By truth, I mean factual truthfulness, not the truth you think should exist. Don’t massage it. In case passive aggressive behaviour is your thing, then the paperwork is not the place to be that person. Bad paperwork is a bit like a mixtape. All the songs and all the lyrics have meaning for you. When you share it with someone else, and they don’t get it, and let’s be honest they were never going to get it, and you’re all crestfallen because you poured all your feelings into selecting each track. Just think had you been factual and truthful you’d probably be on that date. Instead, it’s Saturday night and you’re reading documentation jumble noise with a pop tart chip sandwich for company. Got it? Good.

↑

*Please read*

*Look, this bit is important*

What else as well as accurate, objective and truthful? There’s some gold advice from Crystal Nelson in the podcast so I’ll leave that for Crystal to tell you about it. The other thing is, you must sign the document … with your signature … Y-O-U-R S-I-G-N-A-T-U-R-E. Not initials, not a smiley face, not your crewmate’s signature. Don’t give people reason to doubt your professional character. The war is not fought in the patient’s record.

Here are some additional guidelines for good report writing to not only protects your patient, it will protect you too in the event your paperwork is audited. Patient records must be accurate, complete, contemporaneous, legible and objective. Accuracy is essential – it is important to distinguish between what is personally observed to what is related to the patient’s complaint or illness or injury. In ensuring records are complete, reference should be made where a patient refuses any treatment or medication or acts in a manner contrary to healthcare advice. It is important to provide complete reports but to keep information succinct. Reports should be brief and not include unnecessary detail. Reports should be legibly written, incorrect interpretation of a person’s handwriting can lead to mistakes. Reports should be written objectively. What is required, is an objective, definite and definitive statement of fact by you, the person responsible to the patient for their care. Do not use derogatory, abusive, prejudicial language. Although, I wonder how many times you will write a statement like, Pt told crew to f*** off, in your careers? Many paramedics revel in writing statements like this. It’s one of their secret joys.

- Only write facts

- Record what you heard, saw or did

- Provide clinical information – measurements of clinical signs and results

Entries in records should be made contemporaneously (at the time the incident occurs). It is good practice to make a relevant entry as soon as possible after an incident or an episode of care occurs. HCPs will have better recall of event if recorded at the time. This final point is important. Sometimes demand outstrips available resources. This may mean you do not complete the patient record before getting dispatched to another incident. Sometimes, you will have to access your paperwork again. Depending on the system you use, you may have to provide justification for doing so. There is nothing wrong with this. It helps someone accessing your paperwork understand why you didn’t complete your paperwork before attending another job and completing your paperwork several hours later. It is possible you forgot to include information as well. Check with your service on their policy on this but I would not have an issue you with as long as an adequate and reasonable justification is provided for doing so. If the information is not recorded on the health record, then the court will presume that it did not occur. The court will essentially view the record as regular, complete, and an accurate statement of the events, unless evidence can be submitted to the contrary.[21]

Never, ever falsify records. EVER:

- HCCC v Thompson (No 1) [2012] NSWNMT 13

- Kent v Griffiths [2000] 2 All ER 474

What are the consequences for getting it wrong? Are you kidding? What chapter have you been reading? I’ve laid it all out for you. I just want you to look after your patients, retain your registration and your employment.

Just a final recap of your responsibilities in relation to communication, documentation and record keeping:

- Act ethically

- Respects patient’s autonomy

- Respects patient dignity

- Respects patient’s right to privacy

- Act legally

- Confidentiality

- Privacy

- Health Care Documentation

- Access to Health Records

That’s got to be the end of the chapter? Nope, not even close. Now we discuss professionalism in the context of employment law. I told you it was going to be a big chapter.

3.9 Employment Law

Let us now imagine, for a moment, each and everyone’s future. Except mine. I don’t want to think about that. We’re talking 3-4 years down the line. You’ve graduated, you’ve received your letter of acceptance from the employer of your dreams and you are about to become an employee of an ambulance service or other health service. You will have to sign an employment contract to establish a relationship at law between you and your new employer. A contract is a legally binding agreement between two parties who have come together freely for the purpose of exchange or to provide a service. For an employment contract to exist there must be:

- Acceptance

- Communication

- Certainty

- Consideration

- Capacity and consent

- Legality

Within that employment contract there will be express terms (written or spoken terms) and implied terms that relate to conduct and functionality. For example, no employment contract will ever explicitly prevent you from arriving at work looking like something the cat has dragged in, dishevelled and hungover. Just because it’s not written down does not mean you can rely on it if your boss instructs you to go home on the basis you are not fit for duty. It is a given that conduct of this nature is unacceptable, and no ordinary, reasonable person would ever consider this acceptable. I am tempted to write about mandatory drug and alcohol testing by employers, but I will resist the urge. Instead, I’ll focus on the nature of implied terms in an employment contract. According to the case of BP Refinery (Westernport) Pty Ltd v Shire of Hastings (1977) 180 CLR 266, the implied term:

- must be reasonable and equitable;

- must be necessary to give business efficacy to the contract, so that no term will be implied if the contract is effective without it;

- must be so obvious that ‘it goes without saying’;

- must be capable of clear expression;

- must not contradict any express term of the contract.