Chapter 4 In the Beginning…

Stephen Bartlett

Chapter 4

In the beginning…

4.0 Introduction

The Physician’s Pledge

“AS A MEMBER OF THE MEDICAL PROFESSION:

I SOLEMNLY PLEDGE to dedicate my life to the service of humanity

THE HEALTH AND WELL-BEING OF MY PATIENT will be my first consideration

I WILL RESPECT the autonomy and dignity of my patient

I WILL MAINTAIN the utmost respect for human life

I WILL NOT PERMIT considerations of age, disease or disability, creed, ethnic origin, gender, nationality, political affiliation, race, sexual orientation, social standing or any other factor to intervene between my duty and my patient

I WILL RESPECT the secrets that are confided in me, even after the patient has died

I WILL PRACTISE my profession with conscience and dignity and in accordance with good medical practice

I WILL FOSTER the honour and noble traditions of the medical profession

I WILL GIVE to my teachers, colleagues, and students the respect and gratitude that is their due

I WILL SHARE my medical knowledge for the benefit of the patient and the advancement of healthcare

I WILL ATTEND TO my own health, well-being, and abilities in order to provide care of the highest standard

I WILL NOT USE my medical knowledge to violate human rights and civil liberties, even under threat

I MAKE THESE PROMISES solemnly, freely, and upon my honour”.[1]

*WARNING*

Please be advised that the video below contains strong language. Viewer discretion is recommended.

Philip Larkin’s sardonicism aside, there are some aspects of this unit that lends towards an online format. There are other aspects that don’t. Given the prevalence of some of the issues raised in the unit I believe some of you have personal experience of the adversities described in the chapters in parts 2 and 3. Face to face teaching lets me see how students are responding to some of the matters discussed in this and upcoming chapters. I’m worried that by teaching online entirely, I will lose that opportunity to identify and talk with students who may feel at odds with many of the topics yet to be discussed in the book.

Discussing child maltreatment, domestic and family violence, elder abuse, suicide prevention, end of life care, voluntary assisted dying, modern slavery, racism, sexism, including other topics that can cause distress and elicit a variety of responses. Given your chosen professions it is remiss of me not introduce these topics into your degree. I accept that by doing so I may contribute to students experiencing additional harm. If anything discussed in this unit impacts you, particularly the topics in upcoming chapters, I can be contacted at stephen.bartlett@qut.edu.au or on 07 3138 0139. If you prefer not to speak to me but would like support, I will help connect you with services offered by QUT. I have some trepidation about running tutorials on some of these subject areas. The online world is very different to the classroom. People respond differently, this includes responding not at all in many circumstances. Knowing about these topics are integral to becoming a good HCP. This is the justification for introducing challenging topics in the context of healthcare delivery.

4.1 Conception

When does life begin? Who decides? What is a sentient being? What is a sapient being? When does viability commence? On what grounds should terminations be allowed? Are you kidding? I will not be able to answer any of these questions. What we must do, however, is consider these questions using various ethical and legal principles as we try to pinpoint an answer and understand how asking these questions relate to our practise.

In an alarmingly sexist attitude but perhaps unsurprising for the times, Aristotle attributed life (or possession of a soul) to a male fetus at 40 days from fertilisation and females at 90 days. (Everyone was a right so and so back then. We’re much better now, aren’t we? I’ve just looked at the news. Gracious, we’re not.) Even I know that there were no ultrasounds just under 2.500 years ago. The earliest documentary evidence of ultrasounds being used to determine gender of a fetus was not until the time of Aenesidemus (I may have made that up. No, I definitely made it up.) My point being, how can soul be ascribed to different genders that is dependent on their development in utero? Did Aristotle claim that male souls were older than females at the point of delivery? Pass the wine, Aristotle. You’ve clearly been channelling Dionysus (you want to see the names he gave some of his children) a bit too much. I digress. The basis for Aristotle’s belief may lie in his three-stage theory of life: vegetable, animal, rational. The vegetable stage was reached at conception, the animal at ‘animation’, and the rational soon after live birth.

Fast-forward a couple of millennia, we have a better understanding when legal status is conferred on human life. From an ethical perspective, the answer, as you will imagine is vaguer than that of its legal counterpart definition. Viability of the fetus is a factor in pregnancy. Traditionally, a full-term pregnancy is classed as being 9 months or about 280 days from conception (40 weeks). Pre-term is any live pregnancy occurring before 37 weeks. Babies have been born from 20 weeks and with intensive medicalised care can sometimes survive. In the first trimester, the fetus is not considered viable. During the second trimester consideration will be given to saving the life of the mother and her pregnancy in an emergency. Before viability, the mother’s health and well-being are considered in isolation and given priority. Traditionally there has been no agreement in medicine, philosophy or theology as to what stage of fetal development should be associated with the right to life. Depending on ideological basis for assessing a right to life, some views hold a person is a person from the moment of conception and their status is deserving of protection, even at the expense of the mother’s life. Other views hold the quickening (not the sequel to Highlander) as evidence of the developing fetus’ soul. These are the first fetal movements in the uterus felt by a pregnant woman. In 18th century Britain, it was suggested the stirring in the womb was enough to confer legal status on an unborn child.

The English case of Paton v. British Pregnancy Advisory Service (1978)[2] established that in order to have legal status and therefore immutable rights conferred upon it, a child must demonstrate spontaneous respiratory and cardiac output, and no longer rely on the mother for life support. Is it wrong to use birth as the moment a duty to protect the life of another comes into existence? I suggest that a limited legal status exists to protect the life of the fetus in certain limited circumstances. We will look at this in more detail in section 4.4 below.

4.2 Pregnancy and birth

How many bold claims have I made so far? I’ve lost count. Perhaps, someone can keep a record for me. Anyway, here’s another. Any woman, writing her ideal birth plan, will not write in that birth plan that she would like her baby birthed by paramedics, in an ambulance, by the side of the road. That’s not to say, labouring women do not value the intervention of paramedics. It is just that, if given the choice between hospital, home and an ambulance, a pregnant woman will never choose option 3 unless there is no other viable alternative.

I am not treading on the toes of CSB339/CSB348 but it important to recognise our legal and ethical responsibility to pregnant women. My own experience of birthing babies tends to sit with either one of two extremes. The birthss were always precipitous and either had a positive or a tragic outcome for the patients involved. There was very little in between in terms of antenatal care and often the paramedic role was to transport a pregnant woman to a birth or delivery suite for the midwives and obstetricians to take charge of the pregnant woman’s care. Occasionally conflict occurs between the right to self-determination for the labouring woman with the prospect of a live birth. In cases whereby certain interventions have been proposed with the intended outcome of a live birth and have been refused by pregnant women, obstetricians have been prepared to involve the courts to determine the lawfulness of their proposed actions.

In a series of UK cases dating back to the 1990s the courts examined the refusal of proposed treatment in labour based on religious grounds[3] and refusal to be cannulated based on the labouring woman’s needle phobia.[4] In Re MB (An Adult: Medical Treatment) [1997] 2 F.C.R. 541, Butler-Sloss LJ said:

“A competent woman who has the capacity to decide may, for religious reasons, other reasons, for rational or irrational reasons or for no reason at all, choose not to have medical intervention, even though … the consequence may be death or serious handicap of the child she bears, or her own death. She may refuse to consent to the anaesthesia injection in the full knowledge that her decision may significantly reduce the chance of her unborn child being alive. The foetus up to the moment of birth does not have any separate interests capable of being taken into account when a court has to consider an application for a declaration in respect of a Caesarean section operation. The court does not have the jurisdiction to declare that such medical intervention is lawful to protect the interests of the unborn child even at the point of birth.”

In Attorney-General’s Reference (No. 3 of 1994) [1998] AC 245, Lord Mustill explained:

“The mother and the foetus were two distinct organisms living symbiotically, not a single organism with two aspects. The mother’s leg was part of the mother; the foetus was not … I would, therefore, reject the reasoning which assumes that since (in the eyes of English law) the foetus does not have the attributes which make it a ‘person’ it must be an adjunct of the mother. Eschewing all religious and political debate I would say that the foetus is neither. It is a unique organism. To apply to such an organism the principles of a law evolved in relation to autonomous beings is bound to mislead.”

We will return to this case when I discuss consent in more detail and in chapter 7. As you will have realised, hopefully, by now, different jurisdictions treat the pregnant patient in different ways. From Savita Halappanavar who was not given a termination at Galway University Hospital even though she subsequently developed septicaemia related to her pregnancy that proved to be fatal for Savita. Notwithstanding the changes the cases have made to the legal landscape in various countries, integrity and autonomy remain guiding principles in healthcare.

4.2.1 Domestic violence in pregnancy

“Women are at an increased risk of experiencing violence from an intimate partner during pregnancy”.[5] That’s not the only thing you need to know about domestic and family violence in pregnancy. But as an introduction and as a departure point it doesn’t get more important than that. “Attempted strangulation, along with pregnancy, is an important early indicator of homicide in women”.[6]

HCPs have an important role to perform by acknowledging domestic violence in the communities they work. Although it is not entirely obvious what that role is. Not all HCPs share the view that it is their responsibility to respond to domestic and family violence. I intend to discuss this in detail in chapter 9. However, I need to introduce this topic here as it relates to fetal development and the fetal exposure to domestic violence. HCPs need to be alert to the increased risk of domestic violence in pregnancy as well as the potential harms to the developing fetus, which can lead to low birth weights and even miscarriage. Furthermore, the impact of stress on pregnant women can also impact fetal development.

Paramedics are responsible for providing some antenatal care but their role before birth is limited. Unlike midwives and GPs, paramedics may not have the same opportunity to provide screening for domestic and family violence in pregnancy. This should not preclude paramedics from enquiring about the health status of a pregnant woman more broadly. Not all victims of domestic and family violence will be transported to hospital. Opportunities to prevent violence may be lost in the event of non-transport. There are several barriers paramedics report when responding to domestic and family violence, and child maltreatment. The child maltreatment barriers are reported below, domestic violence barriers in chapter 9. I conclude this section asking students to consider asking whether domestic and family violence exists as backdrop to any woman’s pregnancy they attend in the course of their work.

4.3 Termination of pregnancy

The Termination of Pregnancy Act 2018 (Qld) governs law terminations of pregnancies (ToP) or abortions in Queensland. Before this legislation was enacted the Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) governed the permissibility of ToPs in Queensland. The Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) prior to the enactment of the Termination of Pregnancy Act 2018 (Qld) held:

- 224 Attempts to procure abortion

- Any person who, with intent to procure the miscarriage of a woman, whether she is or is not with child, unlawfully administers to her or causes her to take any poison or other noxious thing, or uses any force of any kind, or uses any other means whatever, is guilty of a crime, and is liable to imprisonment for 14 years

- 225 The like by women with child

- Any woman who, with intent to procure her own miscarriage, whether she is or is not with child, unlawfully administers to herself any poison or other noxious thing, or uses any force of any kind, or uses any other means whatever, or permits any such thing or means to be administered or used to her, is guilty of a crime, and is liable to imprisonment for 7 years.

- 226 Supplying drugs or instruments to procure abortion

- Any person who unlawfully supplies to or procures for any person anything whatever, knowing that it is intended to be unlawfully used to procure the miscarriage of a woman, whether she is or is not with child, is guilty of a misdemeanor, and is liable to imprisonment for 3 years.

According to the case of R v Bayliss and Cullen (1986) 9 Qld Lawyer Reps 8, in order for a termination to be lawful, the doctor must honestly and reasonably believe that the continuation of the pregnancy would result in a serious danger to the woman’s physical or mental health. These reasonable grounds can stem from social, economic or medical bases.

The law on ToPs in Queensland, now governed by the Termination of Pregnancy Act 2018 (Qld) states:

- Section 5

- Termination by medical practitioner at not more than 22 weeks

- A medical practitioner may perform a termination on a woman who is not more than 22 weeks pregnant.

- Section 6

- Termination by medical practitioner after 22 weeks

- (1) A medical practitioner may perform a termination on a woman who is more than 22 weeks pregnant if—

- (a) the medical practitioner considers that, in all the circumstances, the termination should be performed; and

- (b) the medical practitioner has consulted with another medical practitioner who also considers that, in all the circumstances, the termination should be performed.

- (2) In considering whether a termination should be performed on a woman, a medical practitioner must consider—

- (a) all relevant medical circumstances; and

- (b) the woman’s current and future physical, psychological and social circumstances; and

- (c) the professional standards and guidelines that apply to the medical practitioner in relation to the performance of the termination.

- (3) In an emergency, a medical practitioner may perform a termination on a woman who is more than 22 weeks pregnant, without acting under subsections (1) and (2), if the medical practitioner considers it is necessary to perform the termination to save the woman’s life or the life of another unborn child.

- (1) A medical practitioner may perform a termination on a woman who is more than 22 weeks pregnant if—

- Termination by medical practitioner after 22 weeks

- Section 10

- Woman does not commit an offence for termination on herself

- Despite any other Act, a woman who consents to, assists in, or performs a termination on herself does not commit an offence.

- Woman does not commit an offence for termination on herself

- Termination by medical practitioner at not more than 22 weeks

In section 4.1, I put a link to a newspaper article that reported a woman’s death in Galway University Hospital, Ireland. In 2018, the Irish people voted in a referendum (plebiscite) to repeal the 8th amendment of the Irish constitution which outlawed terminations in Ireland. There are countless stories of Irish women travelling to England to obtain a safe termination. Other aspects of this seeps into the history of the Magdalene Laundries also in Ireland. Where ever your views fall on the topic of ToPs, the basis of the legislative changes described above offer women a safe alternative to back street abortionists[7] or procuring drugs to terminate a pregnancy from the internet.

4.3.1 Sterilisation

Now we know that pregnancies can be terminated lawfully. Is it possible to lawfully withhold opportunity from a woman to become pregnant based on the sterilisation without their consent? Is it possible to sterilise males without their consent? The cases of Re F (Mental Patient: Sterilisation) [1990] 2 AC 1 and An NHS Trust v DE [2013] EWHC 2562 (for an important Australian judgment see Secretary of the Department of Health and Community Services (NT) v JWB and SMB (Marion’s case) (1992) 175 CLR 218; the judgment relates to several area of law, including child law and consent (we will return to this in section 4.5) adopt a best interest test.

In Re F (1990), F is an adult and therefore beyond the protection of wardship, she is developmentally delayed. She commenced a relationship with a male patient in her shared care facility. F’s family and medical staff were concerned about the impact of becoming pregnant on F. Other examples of contraception were considered but were not judged appropriate for F. F was unable to provide consent. In the House of Lords (the previous name for the UK’s Supreme Court), Lord Brandon stated:

“The application of the principle which I have described means that the lawfulness of a doctor operating on, or giving other treatment to, an adult patient disabled from giving consent, will depend not on any approval or sanction of a court, but on the question whether the operation or other treatment is in the best interests of the patient concerned. That is, from a practical point of view, just as well, for, if every operation to be performed, or other treatment to be given, required the approval or sanction of the court, the whole process of medical care for such patients would grind to a halt”.[8]

It occurred to me after this case how the courts approach the gendered aspects of sterilisation. I was intrigued by the prospect of male sterilisation without consent. It took 23 years following the House of Lords decision in Re F for this issue to come before the courts. In An NHS Trust v DE [2013] EWHC 2562 the UK High Court had to determine the lawfulness of male sterilisation where consent could not be provided. DE, like F before him, has a developmental learning disability. At the time of the hearing he was living with his parents and had some independence. He was in a longstanding relationship with PQ. DE and PQ had a child which impacted their relationship profoundly. There were doubts whether DE possessed the capacity to consent to sexual relations and the capacity to use contraception. Protective measures were put in place to supervised DE and PQ. Furthermore, DE made it clear he did not want to become a father again. Therefore, the view was formed that the best way to ensure DE’s wishes were respected and restore as much independence as possible to him was by his having a vasectomy. Despite not possessing the testamentary capacity to provide consent to undergo the operation.

These cases help us understand how the courts are prepared to intervene and balance autonomy and human rights with a paternalistic informed best interests’ approach. In the next chapter we will discuss consent and capacity in more detail, but it is enough to state in the meantime, if a person has capacity, they get to choose what is done to their body. Otherwise an allegation of assault can be made against a HCP treating a patient without their consent unless certain conditions prevail. But more on this next chapter, I promise.

4.4 Children’s health law

Children’s health law, despite the misleading title is not a distinct area of health law. However, in the eyes of the law, children are distinct. They are legal entities, yes. But until a person reaches the age of 18, they lack capacity. Capacity, as we will go on and learn is a key attribute of autonomy and self-determination. If a person lacks capacity, they lack autonomy. Which, to add insult to injury is only partly true as capacity is a tricky thing to pin down and define succinctly and unambiguously. Furthermore, the law needs to treat children differently. A power imbalance exists between adults and children. Children’s rights are vested in adult caregivers. Children require additional protections. Conflicts do arise and this is what the next sections are dedicated.

4.4.1 Child maltreatment and Child Protection

Child maltreatment (CM) and child abuse and neglect (CAN) are often used interchangeably. I’ve often struggled with the prefix, ‘mal’. Children suffer harms at the hands of adults and other children for all kinds of reasons. Not all harms can be attributed to malice, malevolence, malfunction, malversation, malignancy, malcontent or anything malefic for that matter. Instead, I am going to host CM and CAN under the term: adverse childhood events (ACEs). ACEs cover much broader issues than CM and CAN and the consequences of ACEs can be as damaging as being a victim of CM and CAN. An ACE will include exposure to community violence, such as a home invasion. Or it can include interpersonal bullying and harassment as well as issues covered by the Modern Slavery Act 2018 (Cth) of which 15,000 victims currently live in Australia. Modern slavery refers to any kind of…

- Slavery

- Servitude

- Trafficking in Persons

- Forced Labour

- Debt Bondage

- Forced Marriage

- Sale of or Sexual Exploitation of Children

Please don’t be misled by this approach. I am not glossing over the harms perpetrated towards and against children. It is just I don’t believe it is accurate to couch CAN as any act or omission that depends on the perpetrator motives. Yes, people who deliberately harm children must be held to account. However, there are many other factors that underpin CAN, such as child poverty. To define a person’s characteristics based on their standard of living is patently wrong. So, I eschew the term maltreatment in favour of adversity. Adversity is inclusive of the many, many ways harm can occur.

In terms of why I believe it is incumbent on all HCPs to be alert to the location of ACEs. Well, it can be summed up by remarks made in the inquiry following the murder of Victoria Adjo Climbié in 2000:

“At the post-mortem examination, Dr Carey recorded evidence of no fewer than 128 separate injuries to Victoria’s body, saying, “There really is not anywhere that is spared – there is scarring all over the body.

Therefore, in the space of just a few months, Victoria had been transformed from a healthy, lively, and happy little girl, into a wretched and broken wreck of a human being.

Perhaps the most painful of all the distressing events of Victoria’s short life in this country is that even towards the end, she might have been saved. In the last few weeks before she died, a social worker called at her home several times”.[9]

These quotes are the introduction into the inquiry. Victoria was 8 years old. There were countless opportunities identified by the inquiry that could, had people and agencies acted saved her life. The report authored by Lord Laming highlighted multiple failures in not just the child protection system but in greater society.[10]

4.4.2 Responding to and reporting responsibilities for HCPs in response to suspected ACEs

“Children, unlike adults, cannot protect themselves; they are dependent on others to shield them from harm”.[11]

“Because EMS providers are often called to the home of the child, they can have an important role in identifying and recording information that many medical and child protection professionals do not have an opportunity to see”.[12]

CAN is defined as occurring based on the following forms and examples:

Child Physical Abuse (CPA), examples may include:

- broken bones or unexplained bruises, burns, or welts in various stages of healing

- attempted strangulation

- the child or young person can’t explain an injury, or the explanation is inconsistent, vague or unlikely

- the parents saying that they’re worried that they might harm their child

- family history of physical violence

- delay between being injured and getting medical help

- parents who show little concern about their child, the injury or the treatment

- frequent visits to health services with repeated injuries, illnesses or other complaints

- the child or young person seems frightened of a parent or carer

- the child or young person reports intentional injury by their parent or carer

- arms and legs are kept covered by clothing in hot weather

- ingestion of poisonous substances including alcohol or drugs

- the child or young person avoids physical contact (particularly with a parent or carer)

Child Sexual Abuse (CSA), examples may include:

- inappropriate sexual behaviour for their age and developmental level (such as sexually touching other children and themselves)

- inappropriate knowledge about sex for their age

- disclosure of abuse either directly, or indirectly through drawings, play or writing

- pain or bleeding in the anal or genital area, with redness or swelling

- fear of being alone with a particular person

- child or young person implies that they must keep secrets

- presence of sexually transmitted infection

- sudden unexplained fears

- bed wetting and soiling

Child Emotional Abuse (CEA), examples may include:

- coercion and control

- parent or carer constantly criticises, insults and puts down, threatens, or rejects the child or young person

- parent or carer shows little or no love, support, or guidance

- child or young person shows extremes in behaviour from aggressive to passive

- physically, emotionally and/or intellectually behind others of the same age

- compulsive lying and stealing

- highly anxious behaviours

- lack of trust

- feeling worthless

- eating hungrily or hardly at all

- uncharacteristic seeking of attention or affection

- reluctant to go home

- rocking, sucking thumb or self-harming behaviour

- fearful when approached by someone they know

Child Exposure to Domestic Violence (CEDV) (The following are taken from section 10 Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 2012 (Qld)

- overhearing threats of physical abuse

- overhearing repeated derogatory taunts, including racial taunts

- experiencing financial stress arising from economic abuse

- seeing or hearing an assault

- comforting or providing assistance to a person who has been physically abused

- observing bruising or other injuries of a person who has been physically abused

- cleaning up a site after property has been damaged

- being present at a domestic violence incident that is attended by police officers

Child Neglect (CN), examples may include:

- signs of malnutrition, begging, stealing or hoarding food

- poor hygiene: matted hair, dirty skin, or body odour

- untreated medical problems

- child or young person says that no one is home to look after them

- child or young person always seems tired

- frequently late or absent from school

- clothing not appropriate to the weather

- alcohol and/or drug abuse in the home

- frequent illness, minor infections or sores

- hunger

Children can experience overlapping forms of abuse; this is referred to as multi-type maltreatment or polyvictimisation.[13] Children exposed to domestic violence “are 3–9 times as likely to be maltreated than children who have not been exposed to domestic violence; more than half (56.8%) of [children exposed to domestic violence] were also maltreated; more than 60% of neglect victims and more than 70% of victims of sexual abuse by a known adult had also witnessed partner violence”.[14] Additionally, the triad or so called toxic trio of parental mental health issues, parental substance abuse and parental violence, the aforementioned toxic trio, are sentinel signs of increased risk of child maltreatment.

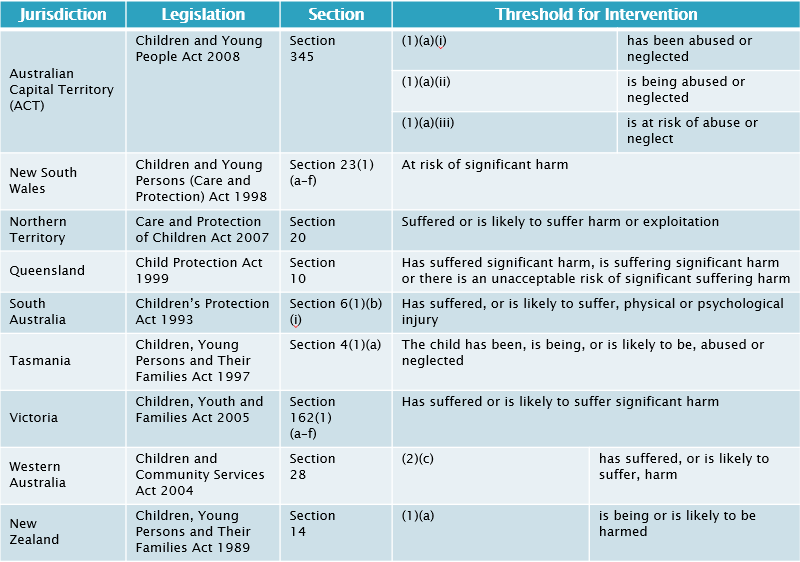

According to section 8 Child Protection Act 1999 (Qld) and section 17 Law Reform Act 1995 (Qld), a child is defined as an individual under 18 years. The following table describes the threshold for services to intervene based on suspected childhood harm or adversity:

Please note the inclusion of the word significant. How does significant harm vary from harm? The legislation does not define the word significant. Perhaps another way of phrasing this question is to pose the nature of harm in the context of chastisement. It is lawful to chastise a child. There comes a point when chastisement is no longer proportionate to its intended aims and it becomes abuse. How would you recognise this point? Responding to issues of child protection is complex and this is often accompanied by the fear of getting it wrong leading to false accusations.

However, the risk of getting it wrong needs to be balanced against the risk of getting it right. Reporting responsibilities vary depending on professions. In Queensland, the laws on reporting suspected child maltreatment require different things from paramedics and from nurses. Key to making reports of high quality requires HCPs to be better informed about ACEs, their causes them and how to identify.

4.4.3 Mandatory reporting of suspected child abuse

The mandatory reporting of suspected child maltreatment applies to doctors and nurses (although not mentioned explicitly, this includes midwives too) in Queensland and is covered by section 158 Public Health Act 2005 (Qld) and section 13E Child Protection Act 1999 (Qld). The reporting requirement only extend to CPA and CSA, and do not extend to CEA, CEDV and CN. In addition to section 13E, section 13A Child Protection Act 1999 (Qld) states:

(1) Any person may inform the chief executive if the person reasonably suspects—

(a) a child may be in need of protection; or

(b) an unborn child may be in need of protection after he or she is born.

(2) The information given may include anything the person considers relevant to the person’s suspicion.

Only because doctors and nurses are mandated to report suspected CPA and CSA this does not prevent or preclude other HCPs from reporting all examples of CAN in Queensland. Sections 159Q and 197A Child Protection Act 1999 (Qld) protects people from liability for giving information in relation to suspected child maltreatment.

I remain to be convinced by mandatory reporting legislation. I am not opposed to it as I believe it has its merits, but I also believe it has drawbacks. One benefit, amongst many, is how mandatory reporting can improve the quality of notifications and therefore increase substantiations. Mandatory reporting also helps remove doubt and can overcome the rule of optimism is relation to acknowledging the presence of CAN. According to Lionel Tiger:

“There is a tendency for humans consciously to see what they wish to see. They literally have difficulty seeing things with negative connotations while seeing with increasing ease items that are positive”.[15]

The application to detection of CAN may not have been in Tiger’s mind when he wrote these words. However, this statement helps us understand how suspected CAN may remain underreported. Tiger’s words form part of the prejudice that we all hold – I can’t believe anyone would do that to another person, therefore it cannot be happening. Based on self-preservation alone, why would we want to consider the prospect of child maltreatment? The prospect of its existence is too horrible to contemplate. Tragically, ACEs do exist . Victoria Climbié’s murder is not unique. There is a litany of abused and murdered children whose names I could but will not document. My aim here is to raise the profile of ACEs in the community, not cause any more distress than is necessary to introduce this topic to you all. I want to impress on you that child protection forms part of your care profile. How obvious suspected CAN is to the practitioner’s eyes and ears is a moot point. Children’s adversity can hide in plain view for years, which ties to Tiger’s words on optimism. If there is any doubt regarding the safety and the welfare of a child whose residence you attend, then act on it. You do not need to be mandated reported to make a notification to child services or the police. You just need to be concerned. Studies are currently being undertaken to reveal the prevalence of CAN in Australia.[16] Once complete, the interface of healthcare provision in the space of ACEs will be better understood. There aren’t too many other professions in Australia that have your reputations and enter people’s home bringing healthcare to the community. Leverage off these reputations and be willing to intervene to support families and prevent CAN before further tragedy develops.

“Placing a mandatory duty on health professionals to report suspected abuse forces the subject of child abuse at the forefront of the health professionals mind when assessing a child for an unrelated problem. This ultimately could benefit the child in the sense that the arousal of suspicion of abuse will be the first step in bringing about the end of the abuse. However, the mandated approach may cloud the health professional’s judgement and may cause the person treating to act defensively in regard to his or her suspicion. Thus placing the liability imposed for not reporting to be more important and serious than the child’s actual welfare. Health professionals will, like social workers, be forced to ask themselves whether ‘this family [can] contain the potential for inflicting death or life-limiting injury to the child, and how will I know?’ Therefore, should a duty be imposed the requirements of that duty must be made clear to health professionals”.[17]

I accept intervention has the potential to damage the therapeutic relationship between HCPs and your patients. Accusations that are not substantiated can be damaging and may deter people from requesting emergency services. I urge you to consider this but fall to the side that favours reporting suspected CAN. We will dedicate time to this topic in tutorials. In the meantime, I will close this section and return to Lord Laming who acknowledged the challenges facing front-line staff responding to scene either backgrounded or foregrounded by CAN:

“I recognise that those who take on the work of protecting children at risk of deliberate harm face a tough and challenging task. Staff doing this work need a combination of professional skills and personal qualities, not least of which are persistence and courage. Adults who deliberately exploit the vulnerability of children can behave in devious and menacing ways. They will often go to great lengths to hide their activities from those concerned for the well-being of a child. Staff often have to cope with the unpredictable behaviour of people in the parental role. A child can appear safe one minute and be injured the next. A peaceful scene can be transformed in seconds because of a sudden outburst of uncontrollable anger”.[18]

Despite the challenges, it’s important to ask yourself questions related to a suspected ACE:

- Whether the child’s presentation could be self-inflicted?

- Whether the child’s presentation could be caused by other children with access to child?

- Whether the reported history could account for the child’s presentation?

Differential diagnosis is a feature of CAN. I’ll leave it to you to Google fifth disease. Child protection is a challenging concept but if this Pressbook has a common theme, it is forewarned is forearmed. Do not be deterred.

Child abuse is challenging to identify. The presence of suspected child abuse may have other associated risk factors. Paramedics do not have a mandatory duty to report in Queensland; they do have a moral obligation (discretionary duty) to report. Nurses do have a mandatory duty to report suspected cases of child abuse. When reporting, choose your words carefully. The language you employ to record any suspected child abuse must be objective, factual and accurate. Report what you observe. And be wary of the person who may bias your view of the situation, for good or for bad. Child protection requires a multi-disciplinary team approach in order to act in the best interest of the child suspected of being abused. But you must have faith in your own capability to identify risk of abuse.

4.4.3.1 Failure to protect a child from a sexual offence and failure to report/disclose sexual offending against a child

On 18 December 2013, the BBC published the following headline:

“Lostprophets’ Ian Watkins sentenced to 35 years over child sex offences”[19]

The reason I write about Watkins is not to draw attention to him or the offences he was found guilty of committing – they are heinous – but to draw attention to another BBC headline:

“Ian Watkins child abuse: South Wales Police criticised”[20]

Despite numerous reports made to police about Watkins:

“Watkins’ arrest for his depraved activities followed only after an arrest for drugs offences”[21]

And,

“Between 2008 and 2012, South Wales Police failed to adequately act on eight reports and three intelligence logs from six people about the former Lostprophets frontman’s intentions”[22]

Watkins is not an isolated a case. History is full of scandalous and depraved stories after scandalous and depraved stories featuring prominent individuals. Often committing offences in plain sight of authorities with the statutory responsibility to intervene. In the past, despite (often multiple) reports about their behaviour, if the individual whom the allegations were made against were in the public eye, allegations were all too often dismissed by those charged with investigation – reporters may have been dismissed for having enmity, idolatry and scorn against those individuals whose behaviours were revealed subsequently to be egregious to the point of utter public dismay, outrage and contempt. And therefore, (considered erroneously) baseless and untrue. But it was the police investigation into drug offences that caused services to sit up and take notice. Appalling isn’t it?

Fast forward a few years and 12,000 or so miles. In August 2017, a Royal Commission released its report on institutional responses to child sexual abuse. Recommendation 7.3 states:

“State and territory governments should amend laws concerning mandatory reporting to child protection authorities to achieve national consistency in reporter groups.”[23]

Recommendation 7.5 states:

“The Australian Government and state and territory governments should ensure that legislation provides comprehensive protection for individuals who make reports in good faith about child sexual abuse in institutional contexts. Such individuals should be protected from civil and criminal liability and from reprisals or other detrimental action as a result of making a complaint or report, including in relation to:

-

- Mandatory and voluntary reports to child protection authorities under child protection legislation

- Notifications concerning child abuse under the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Emphasis added).”[24]

The Criminal Code (Child Sexual Offences Reform) and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2020 (Qld)[25] received assent on 14 September 2020. On 5 July 2021, the Queensland Government implemented the changes, incorporating them into the Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld). The amendments relate to new offences for failure to protect a child from a sexual offence, s229BB Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) and failure to report belief of child sexual offence committed in relation to a child, s229BC Criminal Code 1899 (Qld). These offences place a positive obligation on third parties to report. Failure to do so may lead to criminal conviction and a custodial sentence imposed on the defendant. In Queensland the offences relate to a person under the age of 16, which, as you know is two years younger than the legal definition of childhood and extends to laws of sexual consent in Queensland.

229BB Failure to protect child from child sexual offence

(1) An accountable person commits a crime if—

(a) the person knows there is a significant risk that another adult (the alleged offender) will commit a child sexual offence in relation to a child; and

(b) the alleged offender—

(i) is associated with an institution;[26] or

(ii) is a regulated volunteer; and

(c) the child is under the care, supervision or control of an institution; and

(d) the child is either—

(i) under 16 years; or

(ii) a person with an impairment of the mind; and

(e) the person has the power or responsibility to reduce or remove the risk; and

(f) the person wilfully or negligently fails to reduce or remove the risk.

Maximum penalty—5 years imprisonment.

HCPs could be charged with a failure to protect a child from a child sexual offence if they treat patients who make a disclosure and they do not document the information or share that information with relevant authorities, usually police. Given the legislative definitions, Queensland Health is an institution under this amendment to the Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld)

However, the next section has much broader application and relates to any adult in Queensland, whether they are part of an institutional entity or an ordinary citizen. The section can be accessed here:

https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/whole/html/inforce/current/act-1899-009#sch.1-sec.229BC

Instead of stating the legislation and letting you all work it out for yourselves, which you are welcome to do, by the way. I will break down the failure to report criteria:

- The reporter must be an adult (i.e. 18 years of age and older)

- Belief needs to be based on reasonable grounds (this is an objective standard determined by the reasonable person test)

- The victim must be a child, but not between 16-18 years of age

- Individuals are also required to report if the victim of the sexual offence is a person with an impairment of the mind

- The perpetrator must be an adult (i.e. 18 years of age and older)

- If a person forms a belief a child sex offence has been committed, the reporter must disclose the information to police as soon as reasonably practicable

- Failure to report can be mitigated if the person with a belief of child sex offence has a reasonable excuse not to report

- A reasonable excuse for not reporting a belief is defined as:

- The information has already been disclosed to a police officer

- The adult has already reported the information under another provision

- The Child Protection Act 1999 (Qld), for example

- Despite the offence taking place when a child and the victim is now an adult, the adult can refuse the information to be shared with police

- Disclosing the information would endanger the safety of the victim(s), but not the alleged perpetrator

- A reasonable excuse for not reporting a belief is defined as:

- Individuals cannot rely on privilege as reasonable excuse for withholding a report

- i.e. the seal of confession

- fiducial disclosure

- Finally, an adult, acting reasonably and honestly, discloses information will not be held liable for reporting their belief

- Even if the report is not substantiated upon further investigation examination

- I suspect that if the belief is not considered to be held reasonably and honestly, i.e. deceitfully or maliciously then a reporter may be subject to criminal charge or civil claim. As the offence is new, this may not be answerable for some time.

The changes in mandatory reporting laws are related to child sex offences only. Mandatory reporting laws for nurses remain the same for all other types of child abuse and neglect under s 13E Child Protection Act 1999 (Qld). HCPs must understand the legislation, so they are aware of their role and responsibility under the changes to the Criminal Code 1899 (Qld).

Queensland is not the only state to enact failure to protect from and failure to disclose child sex offence. Victoria’s failure to protect a child from sexual abuse[27] and failure to disclose[28] (report) offences came in to force less recently. The offences are found in the Victorian Crimes Act 1958 (Vic).

Back to Watkins and the police, these offences should do away with the discretion of police to not act on citizen disclosure. Not only is it incumbent on citizens to report, it is relevant that police must investigate allegations from individuals.

Something closer to home – Daniel Hanson. So, if you need further reason to be aware of reporting child sex offences, can this be it?[29]

4.4.4 Cultural and family

If family is the earth, then culture is the sky. Culture surrounds and imbues the raising of children. Culture’s imprint is indelible and the culture we are brought up is an integral and defining characteristic of who we are and who we become. Yet not all aspects of culture are valued in Australia or even permitted.

Female genital mutilation (FGM), cutting or circumcision is performed with the belief that it is in the best interests of the female child; that it will ensure health, chastity, hygiene, societal cohesion, family honour, marriageability, fertility and successful childbirth. It is not attributed to any particular religion and is a cultural rather than religious phenomenon. It is a non-therapeutic act and is associated with poor health outcomes. Not only is it a criminal offence to perform this act in Australia, it is illegal to leave Australia with the intention of obtaining the aforementioned act in countries where the act remains prevalent. Australia is signatory to several international conventions related to its eradication. These include: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948); The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1979); The Convention on the Rights of the Child (1990); The Declaration on Violence Against Women (1993: includes specific reference to FGM). In Queensland, sections 323A and 323B Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) outlaws FGM and removal of a child from the State to obtain FGM. Cases where HCPs might be called to suspected FGM may include possible sepsis in pre and pubertal females with an additional history of recent travel to some sub-Saharan, some Middle Eastern or some Far Eastern countries.

We will return to the topic of culture and family in our final chapter. Australia’s first people have suffered more and are over-represented in the child protection system. We will explore this topic through the lenses of cultural competence and cultural safety. As well as discussing the overall impact of European settlement on culture, it is necessary to acknowledge the prevalence of abuse and its impact on Australia’s first people, emphasising state sponsored maltreatment.

4.4.5 Responding to disclosure

If disclosure is made, REMEMBER: Don’t, despite everything, allow your emotions to surface; do not challenge anyone on scene; let the child know you believe them; be aware that the language the child may employ may not make disclosure clear to you; try to consider the context of what is being stated to you; be aware of differential diagnosis such as conditions that mimic bleeding or urinary tract infections. Above all, try to understand that there may be many reasons for a child’s (challenging) behaviour and refrain from making judgements. Do not pressure children to make a disclosure. Allow them to dictate the pace. Be encouraging but only to the extent it helps a child feel safe. It is important to document as much as you can, not forgetting personal details. The time and date of disclosures must also be documented. Finally, it is okay to acknowledge your own trauma in relation to disclosure. The information shared with you is distressing. It is a privilege to receive a disclosure even though it may not feel like that at the time. It means the person confiding in you sees you as figure representing safety and assurance.

4.5 Gillick competence

I believe it is a bit unfair to introduce the concept of Gillick competence ahead of the chapter on consent and capacity. In keeping with the order of development I include a discussion on children and capacity. Please don’t worry if you find the topic of capacity unclear, it will be better understood in chapter 5.

Generally, legal guardians (biological or adoptive parent[30]) get to make decisions regarding children’s healthcare until they reach the legal age of majority (18 years of age).[31] A ‘child’ is a younger minor who is not likely to have the capacity to provide consent (0-12 years). However, the law is prepared to make exceptions based on a person’s maturity and understanding of their health issue. A ‘young person’ usually refers to an older and more mature minor who may have the capacity to decide (13-18 years).

The cases of Gillick v West Norfolk & Wisbech Area Health Authority (Gillick’s Case) [1987] AC 112 (United Kingdom decision) and Department of Health and Community Services (NT) v JWB (Marion’s Case) (1992) 175 CLR 218 (Australian decision) provide that a young person can make decisions about health care if it can be demonstrated that the young person is sufficiently mature and is capable of understanding the nature and consequences of the decision. There is no set age at which a young person is deemed capable of deciding. The determination is related to maturity and understanding. The level of understanding must be determined having regard for the gravity of risk involved. The test to determine if a young person is capable of understanding is referred to as the ‘Gillick Test’, otherwise known as Gillick competency.

HCPs need to consider age of the young person (the older the child in absence of developmental issues then it is more likely the child will understand proposals from HCPs); the young person’s level of maturity and emotional development; the young person’s level of education and intellect; the young person’s social and family circumstances; the clinical circumstances and the nature of the young person’s physical and emotional condition must be taken into consideration.[32] If the young person demonstrates they have the capacity to consent (maturity, intelligence, understanding of the nature and purpose of the proposed treatment) the child is deemed “Gillick Competent”, the wishes of the child should be respected.

Problems that may be encountered in the out-of-hospital setting may occur when there is no parent or legally authorised representative present to provide consent on behalf of the child. An additional problem occurs when the child/young person and parent are in conflict regarding the decision relating to health care/ambulance services, or the parent refuses to provide consent in circumstances where the child/young person may be exposed to serious physical harm.

According to Marion’s Case (1992) 175 CLR 218 at 310:

“Consent is not necessary where a surgical procedure or medical treatment must be performed in an emergency and the patient does not have the capacity to consent and no legally authorised representative is available to give consent on his or her behalf”.

What if the parent refuses consent, for a child’s, say, blood transfusion?[33]

(1) Where a blood transfusion is administered by a medical practitioner to a child, the medical practitioner or any person acting in aid of the medical practitioner and under the medical practitioner’s supervision in administering such transfusion, shall not incur any criminal liability by reason only that the consent of a parent of the child or a person having authority to consent to the administration of the transfusion was refused or not obtained if—

(a) in the opinion of the medical practitioner a blood transfusion was necessary to preserve the life of the child; and

(b) either—

(i) upon and after in person examining the child, a second medical practitioner concurred in such opinion before the administration of the blood transfusion; or

(ii) the medical superintendent of a base hospital, being satisfied that a second medical practitioner is not available to examine the child and that a blood transfusion was necessary to preserve the life of the child, consented to the transfusion before it was administered (which consent may be obtained and given by any means of communication whatever).

(2) Where a blood transfusion is administered to a child in accordance with this section, the transfusion shall, for all purposes, be deemed to have been administered with the consent of a parent of the child or a person having authority to consent to the administration.

(3) Nothing in this section relieves a medical practitioner from liability in respect of the administration of a blood transfusion to a child, being a liability to which the medical practitioner would have been subject if the transfusion had been administered with the consent of a parent of the child or a person having authority to consent to the administration of the transfusion.

Parental responsibilities relate to the care, welfare and development of the child. Parents must act in the best interests of the child. Refusing lifesaving treatments may not be in best interests of child and the courts can intervene.[34] Section 18 Child Protection Act 1999 (Qld) permits the state to take a child into custody if a state authorised individual (commonly a police officer) reasonably believes a child is at risk of harm and the child is likely to suffer harm if the officer does not immediately take the child into custody. HCPs may consider contacting the Queensland Police Service (QPS) if they have reasonably held concerns that a parent exercising their right to make decision on behalf of a child, they have legal responsibility for is at odds with the well-being of that child. Section 9 Child Protection Act 1999 (Qld) defines harm as any detrimental effect of a significant nature on the child’s physical, psychological or emotional wellbeing.

Returning to Gillick competency, the video below describes what can happen when a child’s wishes conflict with paternalistic views on best interest. The video hints at when the courts may become involved to make decisions on what a child can provide lawful consent.

4.6 Final word

4.7 Case study

Fidelma Hanratty-Verso has gone into labour 5 days after her due date. This is Fidelma’s second pregnancy. In her previous pregnancy, Fidelma was induced into labour due to concerns about the size of the baby she was carrying. She described her previous experience of labour as one of the most traumatic events of her life and responsible for her experiencing post-natal depression. During her previous pregnancy she was diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). There was discussion that Fidelma should be prescribed metformin during that pregnancy, but it was decided that Fidelma managed her glucose levels appropriately and her diabetes could be adequately controlled by diet. Fidelma’s ultrasound scans repeatedly showed that her fetus was big for dates. The sonographers, the midwives and the obstetricians told Fidelma she was going to have a big baby; they expected it to be approximately 10lbs or 4.5kgs. Fidelma was informed by her obstetric team that to ensure the safe delivery of her baby she would need to be induced on her due date. Despite the induction, Fidelma struggled to get into fully established labour at any point after the prostaglandin gel and cook’s catheter had been inserted. Fidelma was examined several times by a midwife and Fidelma appeared to make progress. Despite being fully dilated either due to exhaustion or other reasons the labour did not advance within the recommended safe timeframe based on local health guidelines. The theatre was prepared for an emergency section but just as Fidelma was about to be moved from her delivery room in the birth suite, she began to push. Despite the progress, concerns remained, and the obstetrician delivered Fidelma’s daughter using the ventouse method of delivery. The insertion of the vacuum cup resulted in a 3A degree tear. Fidelma’s daughter (first live birth) had a birth wight of 7lbs or 3.19kgs. Her daughter had an APGAR (don’t worry, all this will become clear in CSB339/CSB348) of 3 at one minute, 8 at five minutes and 10 at fifteen minutes. Fidelma believes the errors identifying the projected weight of her baby contributed to her obstetric team making decisions that prevented her from having a normal vaginal delivery. Fidelma believes she should never have been induced based on the projected weight. She also believes that if she had been allowed to go into labour and progress naturally, she would not have required a ventouse or suffered a tear, and therefore not go on to experience post-natal depression. Fidelma remarked soon after to her partner that if she were to get pregnant again, she would only deliver at home with a birth doula for support.

Twenty months on, Fidelma is in labour again. She is at home. She is supported by Morfydd, her birth doula. Six weeks prior to today, Fidelma completed a birth plan, witnessed by Morfydd. At the time of writing Fidelma stated she had testamentary capacity and the purpose of the birth plan was to state her wishes in relation to the birth of her second child. Fidelma stated on several occasions in the document that she would not, under any circumstances attend any hospital and would only deliver her baby at home naturally, even if paramedics had to be called.

Morfydd has called 000 requesting paramedics for Fidelma. Fidelma developed GDM in pregnancy again. Despite managing her blood glucose levels well again, and following a good health regimen in keeping with her antenatal care, it appears this time her baby’s suspected birth weight could be nearer to 10lbs or 4.5kgs. Fidelma delivers her baby’s head but the second stage ceases to progress due to a suspected shoulder dystocia. Paramedics, including a critical care paramedic arrive within 3 minutes of the call being made. They follow their guidelines and despite all their interventions they are unable to dislodge the baby’s shoulder from Fidelma’s pubic bone. The paramedics were made aware of Fidelma’s birth plan as soon as they arrived. Morfydd repeated several times that at no point Fidelma is consenting to be transported to hospital.

You know the law. You know the ethics. What do you do?

4.8 Podcast

With Strategic Senior Research fellow, Dr Divya Mehta

4.9 Further reading

Townsend, Ruth and Morgan Luck, Applied Paramedic Law, Ethics and Professionalism (Elsevier, 2nd ed, 2020) pp 177-196

Preston, Noel. Understanding Ethics. The Federation Press. 4th edition 2014 pp 106-126 (This chapter, extends to all of part 2 of the Pressbook. It might be worth leaving it until you get to the end of part 2.

Moritz, Dominique (ed), Paramedic Law and Regulation in Australia (Thomson Reuters (Professional) Australia, 2019) pp 237-247

- https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-geneva/. ↵

- Paton v. British Pregnancy Advisory Service Trustees and Another [1979] QB 276 per Sir George Baker: 279. ↵

- Re S (ADULT: REFUSAL OF TREATMENT) [1992] 3 WLR 806. ↵

- Re MB (Medical Treatment) [1997] 2 FLR 426. ↵

- https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/sites/default/files/publication-documents/cfca-resource-dv-pregnancy.pdf. ↵

- Bartlett, Stephen, 'Paramedics and Children Exposed to Domestic Violence' (PhD Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, 2019) https://eprints.qut.edu.au/133879/. ↵

- Vera Drake (a fictitious film) and 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (also a fictitious film). Both stories revolve around historic access to unlawful terminations of pregnancy. ↵

- Re F (Mental Patient: Sterilisation) [1990] 2 AC 1 at 56. ↵

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/273183/5730.pdf. ↵

- Laming, Lord, 'The Victoria Climbié Inquiry' (2003). ↵

- Hayes M. Reconciling protection of children with justice for parents in cases of alleged child abuse. Legal Studies 1997 17(1) 16. ↵

- Markenson D et al 2002 Knowledge and attitude assessment and education of prehospital personnel in child abuse and neglect: Report of a national blue ribbon panel. Prehospital Emergency Care 6(3): 261–272. ↵

- https://aifs.gov.au/publications/family-matters/issue-93/multi-type-maltreatment-and-polyvictimisation ↵

- Hamby, Sherry et al, 'The overlap of witnessing partner violence with child maltreatment and other victimisations in a nationally representative survey of youth' (2010) 34(10) Child Abuse & Neglect 734. ↵

- Tiger, L. (1979). Optimism: The biology of hope. New York: Kondansha International. ↵

- https://www.australianchildmaltreatmentstudy.org/ ↵

- Brandon, M et al Safeguarding Children with the Children Act 1989 (1999) The Stationery Office p 63. Quoted in: FORTIN, Jane. Children’s Rights and the Developing Law. 2nd Edition. LexisNexis Butterworths. 2003. p 458. ↵

- Laming, Lord, 'The Victoria Climbié Inquiry' (2003). ↵

- https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-25412675 ↵

- https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-41039284 ↵

- https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-41039284 ↵

- https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-41039284 ↵

- https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/final_report_-_recommendations.pdf at page 17 ↵

- https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/final_report_-_recommendations.pdf at page 18 ↵

- https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/html/asmade/act-2020-032 ↵

- Examples of institutions—schools, government agencies, religious organisations, hospitals, childcare centres, licensed residential facilities, sporting clubs, youth organisations ↵

- Section 49O Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) ↵

- Section 327 Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) ↵

- https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-07-15/former-band-front-man-jailed-for-raping-14-women-and-girls/100291944?fbclid=IwAR2Dh3vV60yw-1GSQClPDxPLFml8yrt6oJhEm2bbC5_IgTZb3jQ4oUcU6QY ↵

- Sections 61C-61F Family Law Act 1975 (Cth). ↵

- Section 17 Law Reform Act 1995 (Qld). ↵

- https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/143074/ic-guide.pdf. ↵

- Section 20 Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1979 (Qld). ↵

- Minister for Health v AS (2004) 33 Fam LR 223 and Director-General, Department of Community Services v M [2003] NSWSC 532. ↵