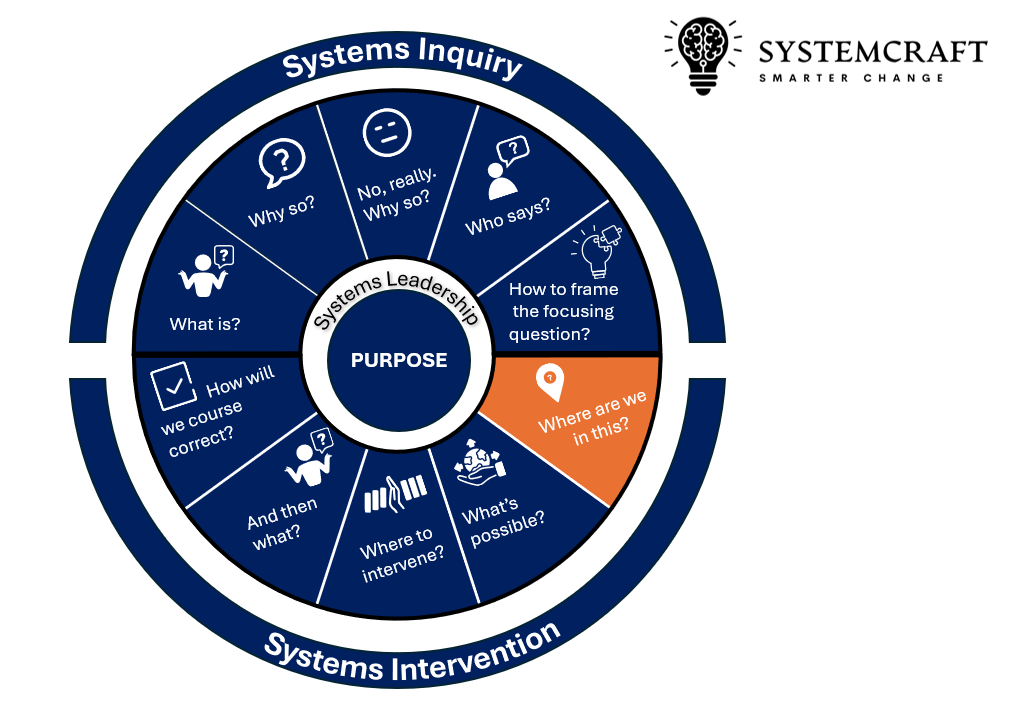

14 Where are we in this?

Figure 11. Systemcraft. Where are we in this? (Joyner, 2025)

Reflecting on our role in perpetuating the current system and our interests in systems intervention.

As the last element in Systems Inquiry, we looked at the idea of the Focusing Question as the bridge between Systems Inquiry and Systems Intervention. In Systemcraft, this step exemplifies the shift from merely understanding the system to actively engaging with it, a shift that requires both rigor and humility.

The first question in Systems Intervention, ‘Where are we in this?’ helps with both these requirements (rigor and humility). This question is not merely about identifying our role in the system but about developing a conscious and reflexive awareness of our agendas, assumptions, and contributions within the system. It is about peeling back layers to understand how we shape, and are shaped by, the very systems we aim to change.

OUR Payoffs FROM the Status Quo

To engage in meaningful system change, we must start by recognising the payoffs we receive from the status quo (Stroh, 2015). Systems persist because they serve purposes; some of those purposes benefit us. Are we benefiting from privileges, conveniences, or efficiencies that the current system affords? For example, in an organisation with hierarchical decision-making, leaders might benefit from clarity of authority, even if this inhibits innovation or inclusivity. We might not want to invest the time and energy in even crucial systems change and thereby enjoy the peace of inertia.

The Sacrifices We’re Prepared to Make

Change demands trade-offs. Once we recognise the benefits we derive from the current system, we must ask which of these benefits we are willing to sacrifice. Real change often requires giving up something we value: resources, comfort, influence, or even cherished beliefs. If we are unwilling to make sacrifices, our calls for change risk being superficial. Systems change for the common good requires integrity, and integrity starts with being honest about what we are prepared to lose for the sake of a better system.

The Payoffs of System Change

Equally important is examining what we stand to gain from the change we propose. This idea is what Baddely and James (1987) describe as ‘carrying.’ When we advocate for system change, are we unconsciously ‘carrying’ an agenda that aligns with our personal goals or ambitions? For instance, an executive might support restructuring to enhance efficiency but overlook how this change consolidates their own power. Reflexivity involves acknowledging these agendas, not to invalidate them but to bring them into conscious awareness. Transparency about our motives allows for more authentic collaboration with others in the system.

Positionality: Seeing the Water

David Foster Wallace’s famous analogy of the fish and water is a powerful metaphor for positionality. Fish do not see the water they swim in; just as we often fail to see the assumptions, perspectives, and worldviews that shape our actions. Yet these perspectives are not neutral; they colour our understanding of the system and influence the changes we propose. For example, a policy maker trained in economics may naturally gravitate toward market-based solutions, overlooking cultural or social dynamics that could offer more sustainable outcomes.

Becoming conscious of the ‘water’ in which we swim requires us to step outside our habitual ways of thinking. Tools like perspective-taking, stakeholder engagement, and critical reflection can help us uncover hidden biases and broaden our understanding of the system. Systems thinking requires the ability to hold multiple perspectives simultaneously.

How Are We Contributing to the Problem?

Finally, we must confront a difficult truth: we are not merely observers of problematic systems; we are participants in them. As nodes in the network, our behaviours, decisions, and assumptions help sustain the very issues we wish to address. For instance, a leader advocating for workplace wellness might unintentionally perpetuate stress by setting unrealistic deadlines or failing to model self-care. Recognising our contribution to systemic problems is not about self-blame but about accountability. It allows us to identify leverage points where we can change our own behaviour to influence the system more positively.

Example

Case Study Analysis: Reflexivity (Where are we in this?) when instigating Organisational Cultural Change. Cricket Australia

Case Overview

Following the Sandpapergate scandal, the Board and Management of Cricket Australia recognised the need for cultural change to restore integrity and trust in the organisation. (Grey, 2019)

Below are the kinds of responses that would provide some insight to the Where are we in this? question which may engender both rigor and humility, ensuring that leaders examined not only their role in the system but also their assumptions, agendas, and contributions to the existing culture.

Recognising the Payoffs of the Status Quo

Systems persist because they serve a purpose. Cricket Australia’s leadership benefited from a results-driven culture that rewarded winning at all costs, even if it fostered ethical blind spots. Hierarchical decision-making gave clarity and control but stifled transparency. Acknowledging these payoffs would be the first step in understanding why cultural problems endured.

How We Are Contributing to the Problem

Leadership decisions, implicit expectations, and performance pressures all contributed to a culture where ethical concerns were overlooked. The prioritisation of results over values created an environment where players felt compelled to push boundaries. Without recognising their role in enabling this culture, leaders risk implementing surface-level changes that failed to address root causes.

What We Are Willing to Sacrifice

Meaningful change requires trade-offs. Leaders would need to recognise that must relinquish some control, prioritise ethical conduct over short-term victories, and redefine success beyond performance metrics. Without this, calls for change would remain superficial.

The Payoffs of System Change – Recognising Tacit Agendas

Leaders must critically reflect on whether they carry tacit agendas into the change process. Those who propose intervention need to identify personal motivations that may unconsciously shape reform efforts. By surfacing their motives leaders can ensure their advocacy for change is grounded in integrity and broader organisational good.

Reflecting on Positionality

Cricket Australia’s leaders must examine how their own backgrounds, experiences, and power influence their approach to cultural change. Positionality affects decision-making, as those who have benefited from past structures may struggle to see the full extent of needed reform. The Cricket Australia Board and Management may move in powerful, but insular circles and fail to recognise the perspectives and needs of players and management at the state and regional levels.

Leaders should engage with diverse perspectives, question their assumptions, and foster a culture of self-awareness. By recognising their own biases and privileges, they can better facilitate an inclusive and sustainable transformation.

Reflexivity as a Practice

Reflexivity is not a one-time exercise; it is a continual practice of examining our role in the system. It involves asking questions like:

- What assumptions am I making about this system and its problems?

- How do my perspectives, training, or experiences shape my understanding of this issue?

- What are my motivations for proposing change, and how might they influence my approach?

- What behaviours or decisions of mine are contributing to the problem I seek to solve?

By asking these questions, we cultivate a deeper awareness of our positionality and begin to see ourselves as part of the system’s dynamics.

Key Takeaways

The Power of Humility

Acknowledging our agendas, assumptions, and contributions to systemic issues requires humility. It means accepting that we are not objective observers but deeply embedded participants. This humility is not a weakness but a strength. It allows us to approach system change with curiosity, openness, and a willingness to learn from others.

When we ask, ‘Where are we in this?’ we acknowledge that system change is as much about transforming ourselves as it is about transforming the system. It is an invitation to engage deeply with our own motivations, to step into the discomfort of self-reflection, and to emerge as more conscious, intentional change agents.

Clarity and Integrity

In the Systemcraft frame, understanding ‘Where are we in this?’ is not a detour but a foundational step. It grounds us in reflexivity, helping us navigate the complexities of system change with greater clarity and integrity. As we move forward, we commit to seeing the water, naming the agendas we carry, and holding ourselves accountable for the roles we play. Only then can we engage in system change that is not only effective but also authentic and ethical.

References

- Baddeley, S. & James, K. T. (1987). Owl, fox, donkey, or sheep: Political skills for managers. Management Education and Development, 18(1).

- Grey, A. (2019). Will Cricket Australia ever regain the public’s trust? Australian Institute of Company Directors. October 1.

- Joyner, K. (2025) Systems thinking for leaders. A practical guide to engaging with complex problems. Queensland University of Technology. https://qut.pressbooks.pub/systemcraft-systems-thinking/

- Stroh, D. P. (2015). Systems thinking for social change: a practical guide to solving complex problems, avoiding unintended consequences, and achieving lasting results. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Wallace, D. F. (2009). This is water: some thoughts, delivered on a significant occasion, about living a compassionate life (1st ed.). Little, Brown.

The recognition of how an individual’s social, cultural, and personal context, such as their identity, background, and perspective, shapes their understanding, interactions, and approach to analysing systems or issues.

The Sandpapergate scandal erupted during Australia's 2018 Test cricket tour of South Africa when Cameron Bancroft was caught on camera using sandpaper to tamper with the ball. Captain Steve Smith and vice-captain David Warner were found to have orchestrated the plan, leading to public outrage. Cricket Australia handed Smith and Warner year-long bans, while Bancroft received a nine-month suspension. Coach Darren Lehmann resigned amid the fallout. The scandal deeply damaged Australian cricket’s reputation, prompting cultural reviews and leadership changes. It highlighted ethical failures in elite sport and sparked broader debates about the pressures of winning at all costs.

The ability to critically examine one’s own beliefs, assumptions, and actions, and how they influence and are influenced by the surrounding system or context.