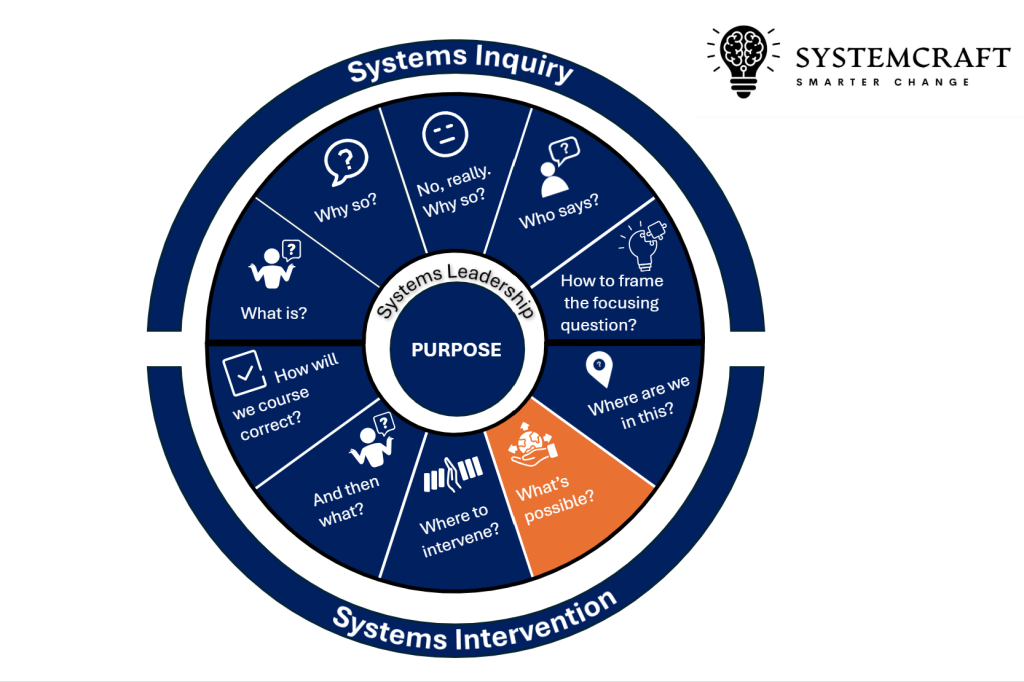

15 What’s possible?

Figure 12. Systemcraft. What’s possible? (Joyner, 2025)

Identifying the opportunities for plausible and feasible and viable change in a complex system.

The Systems Intervention phase of the Systemcraft framework tackles the formidable challenge of system change. While it’s tempting to leap toward envisioning ideal outcomes and strategies, seasoned strategists understand that effective change begins by asking, “What’s possible?” This phase is not just about theoretical solutions but about identifying achievable pathways within the intricacies and dynamics of a system.

Example

An Extreme Example: The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

Few situations exemplify the complexity and intractability of systems better than the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Tony Klug (2019) Middle East advisor, captures this dilemma:

Sandwiched between the mantras of ‘There is no alternative to the two-state solution’ and ‘The two-state solution is dead,’ the contemporary debate over how to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been reduced to little more than a shouting match between two absolutist camps, both certain that they are correct. It is possible that they both are.

It is conceivable that the two-state solution is effectively dead—or at best in intensive care—and, at the same time, that there is no plausible alternative. If both claims are indeed true, we will have to brace ourselves for a future of perpetual conflict with all its toxic overflows. This is a horrendous scenario, but it is not preordained. It depends on decisions that human beings make.

This sobering perspective exemplifies the realpolitik of systemic interventions. While many commentators approach such issues with a prescriptive mindset (“here’s the solution, what’s the problem?”), Klug (2019) highlights the harsh reality: sometimes, accommodation within a system cannot be achieved. His criteria—plausibility and feasibility—offer critical insights. Plausibility refers to solutions credible within the system’s current context, while feasibility reflects the actionable nature of solutions given existing constraints.

Klug suggests that the two-state formula remains the only plausible solution. However, its feasibility diminishes daily. This divergence between plausibility and feasibility underscores the importance of assessing what is possible, not just what is ideal.

Critical Systems Thinking and Systems Dynamics in “What’s Possible?”

When addressing the question of ‘What’s possible? in systems intervention, critical systems thinking (CST) offers a particularly useful paradigm. CST emphasises the importance of framing systems with an awareness of power dynamics, conflicting stakeholder interests, and diverse perspectives. Peter Checkland’s Soft Systems Methodology (SSM), as part of this paradigm, encourages exploring solutions that accommodate differing needs and values rather than seeking a single ‘optimal’ outcome. This makes CST invaluable for tackling wicked problems in contested environments, where integrating diverse viewpoints is essential to crafting viable interventions.

However, systems dynamics also has utility, especially in scenarios where understanding feedback loops and long-term consequences is critical. For example, in addressing environmental sustainability or healthcare reform, systems dynamics can help predict the cascading effects of interventions and identify leverage points for action. While it may not directly resolve the political or social tensions addressed by CST, its focus on the structural and behavioural patterns within systems provides a complementary lens for evaluating feasibility and scalability.

Together, CST and systems dynamics form a robust toolkit for exploring what is possible in complex systems: CST ensures solutions remain grounded in the human and political dimensions of systems, while systems dynamics offers clarity on systemic behaviour over time.

Navigating Diverse Perspectives and Agendas

Klug’s emphasis on plausibility aligns with Peter Checkland’s (1981) Soft Systems Methodology (SSM), which acknowledges the diversity of agendas and perspectives within systems. Rather than seeking a single “optimal” solution, SSM encourages the exploration of models that accommodate conflicting needs and priorities. This collaborative process often reveals new pathways for action that may not be visible through narrower lenses.

Similarly, Gerald Midgley’s (2000) concept of accommodation of interests highlights that system progress does not require perfect alignment among stakeholders. Instead, it calls for a way forward that acknowledges and integrates critical needs and concerns. However, Midgley also cautions that accommodation is not always possible. In such cases, systems may need to dissolve and be reimagined, a radical but sometimes necessary step.

The Spectrum of Wicked Problems

Nancy Roberts’ (2000) work on wicked problems emphasises that not all issues are equally intractable. Wicked problems exist on a spectrum, with some being more tractable than others. Partial solutions or temporary accommodations may be possible in some cases, while others require entirely new ways of thinking or acting. Recognising where a problem sits on this spectrum allows leaders to calibrate their expectations and tailor their strategies. Our assessment is based on

- the level of conflict present in the problem-solving process,

- the distribution of power among stakeholders, and

- the degree to which power is contested

Political Judgment and the Art of Assessing What’s Possible

Those who seek system change must also demonstrate political judgment and astuteness in assessing whether this is the right time to intervene. As John Kingdon’s (2011) concept of ‘windows of opportunity’ reminds us, what is possible is not static. Opportunities for change are shaped by shifting dynamics, such as political will, public opinion, or resource availability. A solution that was impossible yesterday may become achievable today, and vice versa.

This dynamic interplay of timing and context requires what Isaiah Berlin (1996, p47) describes as the essence of political judgment:

Political judgment is a capacity to grasp the unique combination of characteristics that constitute this particular situation—this and no other. It is what used to be called prudence and is indeed a form of knowledge; but it is not reducible to rules, and its application is an art that requires a sense of what fits with what, what can be done in given circumstances, and what cannot.

Berlin’s words highlight the craft of systems intervention: balancing the art of navigating complexities with the prudence to identify when and how to act. This underscores the importance of not only having good ideas but also ensuring that the system is in a state where those ideas can take root and flourish.

Key Principles for Systems Intervention

The common thread in these ideas is the need to navigate realistic possibilities for change within complex systems. Effective systems intervention requires more than idealistic aspirations: it demands a nuanced understanding of the system’s dynamics and a careful assessment of what is achievable.

Crafting Change in Complex Systems

Together, these principles put the ‘craft’ into Systemcraft: they reinforce the idea that systems intervention is a blend of vision and pragmatism. Leaders must balance ideal aspirations with practical approaches, ensuring that progress is both visionary and achievable.

Key Takeaways

Key Principles for REALISTIC Systems Intervention

The common thread in these ideas is the need to navigate realistic possibilities for change within complex systems. Effective systems intervention requires more than idealistic aspirations: it demands a nuanced understanding of the system’s dynamics and a careful assessment of what is achievable.

Key principles include:

- Dynamic Timing and Context: Opportunities for action (Kingdon’s windows of opportunity) are fleeting and must be seized at the right moment.

- Checkland’s SSM and Midgley’s accommodation of interests emphasise finding a way forward that stakeholders with varied viewpoints and concerns can live with (rather than finding consensus).

- Klug’s criteria of plausibility, feasibility, and viability anchor change efforts in reality.

- Roberts’ spectrum of wicked problems underscores the importance of tailoring strategies to the tractability of the issue.

References

- Berlin, I. (1996). The Sense of Reality: Studies in Ideas and Their History. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Checkland, P. (1981). Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Joyner, K. (2025) Systems thinking for leaders. A practical guide to engaging with complex problems. Queensland University of Technology. https://qut.pressbooks.pub/systemcraft-systems-thinking/

- Kingdon, J. W. (2011). Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (Updated 2nd ed.). Boston: Longman.

- Klug, T. (2019). Is there a plausible alternative to the two-state solution? Palestine-Israel Journal. Vo1. 24 (1).

- Roberts, N. (2000). Wicked Problems and Network Approaches to Resolution. International Public Management Review, 1(1), 1–19.

- Midgley, G. (2000). Systemic Intervention: Philosophy, Methodology, and Practice. New York: Springer.

A political approach grounded in practical considerations, power dynamics, and the realities of a situation, rather than being driven by ideology, ethics, or moral principles. It emphasises pragmatism, the pursuit of achievable goals, and the effective use of resources in navigating complex or contested systems.

Complex issues with no clear solution, characterized by interconnected factors, conflicting stakeholder perspectives, and evolving constraints, making them resistant to traditional problem-solving approaches