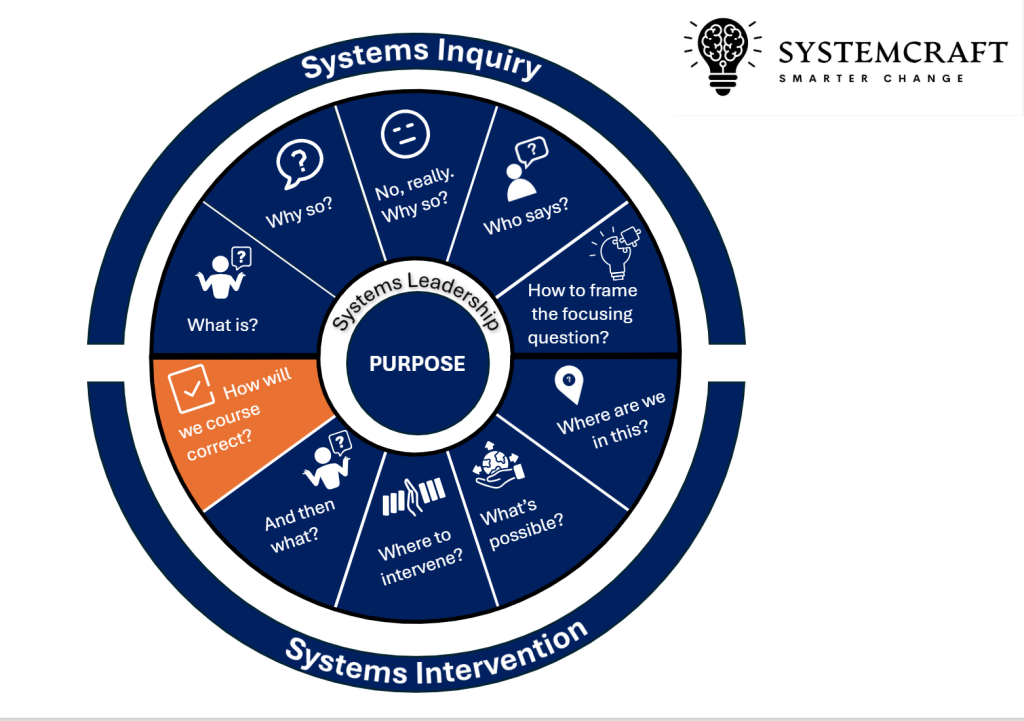

18 How will we course correct?

Figure 15. Systemcraft. How will we course correct? (Joyner, 2025)

Identifying how we are structured to gather and act on feedback, both expected and emergent.

Organisations exist within a dynamic environment, shaped by customers, competitors, regulations, and internal structures. To remain effective and sustainable, they must continuously sense, interpret, and respond to changes in these areas. If organisations fail to maintain strong feedback loops, they become closed systems; insular, slow to change, and prone to systemic failures. In the private sector, companies can miss changes in technology and consumer behaviour (think Kodak). In the public sector, the findings of numerous Royal Commissions show how departments and agencies fail to heed the signals of distress and dysfunction in the communities they serve.

In the systems field cybernetics is the science of feedback, control, and communication in systems, whether in machines, nature, or organisations. At its core, cybernetics helps us understand how complex systems regulate themselves and respond to changes in their environment. It is an illuminating methodology for business-as-usual; it also helps guide the ‘probe, sense, respond’ process following a systems intervention. Think of cybernetics as a GPS for organisations; it helps them navigate complexity, adjust to new conditions, and stay on course. Whether improving governance, streamlining operations, or fostering innovation, cybernetic thinking enables organisations to be adaptive, resilient, and effective in an ever-changing world.

In this chapter we will step through a short history of the field of cybernetics, explore the Viable Systems Model and then turn again to Robodebt for illustration and cautionary tale.

Short History of Cybernetics

As we saw in our History of Systems Thinking, cybernetics emerged in the 1940s, pioneered by Norbert Wiener (1948), who explored feedback loops in machines and living systems. The field drew from engineering, biology, and social sciences, influencing automation, artificial intelligence, and organisational theory. Stafford Beer (1972) applied cybernetics to management, developing the Viable System Model to help organisations self-regulate. In the 1970s, second-order cybernetics shifted focus to the observer’s role in systems. Cybernetics has since shaped fields like AI, complex systems, and governance. Though overshadowed by systems science, its principles remained vital for understanding adaptation, resilience, and feedback-driven decision-making in an increasingly interconnected world. It has recently been rediscovered with discussions in academic and professional circles indicating a renewed interest in applying cybernetic principles to modern issues. For example, the Australian National University recently established a School of Cybernetics. Also, Dan Davies’ recent book The Unaccountability Machine (2025) seeks to reintroduce cybernetics to a new audience, by re-explaining Stafford Beer’s thinking.

This renewed attention underscores the enduring relevance of Beer’s insights into organisational adaptability and self-regulation. As another element of the Who Says, Stafford Beer’s (1972) keen interest in designing decision making systems that reduce, to the extent you can, the power differentials in a group process is also a useful perspective in an era where social inequality is a global issue.

The Viable System Model (VSM)

Within the cybernetics tradition, the Viable System Model (VSM), developed by Stafford Beer (1985), is a way of understanding how complex organisations can survive, adapt, and thrive in a constantly changing environment. It is based on the idea that for any organisation, whether a business, government department, or community group, to be viable (i.e., capable of surviving long-term), it must be structured in a way that allows it to manage complexity effectively.

At its core, the VSM describes an organisation as a living system, like the human body or an ecosystem, where different parts must work together in a balanced way to keep things running smoothly. Beer identified five key systems that must be present for an organisation to be truly viable.

Figure 16. Stafford Beer (1972) The Viable Systems Model. (“VSM Default Version English with two operational systems” by Mark Lambertz is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0)

Tool – Viable Systems Model (illustration of Beer (1972)

The Five Systems of the VSM

Think of an organisation like a human body: the brain, nervous system, and organs all play distinct roles to ensure survival. The VSM breaks this down into five interconnected systems, each responsible for a different function:

1. System 1 – Operations (The Organs of the Body)

- These are the core activities of the organisation; the teams, units, or departments that actually do the work.

- Example: In a retail company, System 1 includes the stores, warehouses, and customer service teams.

- Risk if missing: If operations aren’t functioning properly, the organisation won’t be able to deliver its products or services effectively.

2. System 2 – Coordination (The Nervous System)

- This ensures that different parts of the organisation work in harmony and don’t create conflicts or inefficiencies.

- Example: A logistics team ensures that stock arrives at stores on time and in the right quantities.

- Risk if missing: Without coordination, different parts of the organisation may compete or work at cross-purposes, leading to confusion and inefficiency.

3. System 3 – Management (The Brain’s Control Centre)

- This system oversees day-to-day operations, making sure everything is running smoothly, and resources are allocated properly.

- Example: A CEO or senior leadership team that sets policies, monitors performance, and intervenes when needed.

- Risk if missing: Without effective management, departments or teams might act independently, causing the organisation to become fragmented.

4. System 4 – Strategy and Adaptation (Looking to the Future)

- This system is responsible for scanning the environment, anticipating future challenges, and planning strategic responses.

- Example: A company’s R&D team that monitors industry trends and develops new products to stay ahead of competitors.

- Risk if missing: Without a future-focused system, organisations become stagnant and struggle to adapt to external changes.

5. System 5 – Policy and Identity (The Organisational ‘Self’)

- This system defines the organisation’s core purpose, values, and decision-making principles.

- Example: A government agency’s mission statement that ensures all policies align with public service values.

- Risk if missing: Without clear identity and direction, organisations lack a unifying vision and can become reactive rather than proactive.

The VSM as an Organisational Health Check

As well as a GPS, think of the Viable System Model like a health check for organisations. If one or more of these five systems is weak or missing, the organisation becomes less effective, less adaptive, and more likely to struggle in an uncertain world.

In dysfunctional organisations, System 3 may be weak (poor oversight), System 4 disconnected (ignoring external risks), or System 5 compromised (leadership prioritises short-term interests over ethics).

Feedback loops are essential for identifying these weaknesses and maintaining stability in an organisation. They prevent excessive deviations from norms by applying corrective pressures. However, dysfunction occurs when feedback loops cannot function. For example, the following table illustrates the different types of disfunction from missing feedback loops.

| Failure Type | Cause | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Corrective Feedback | No mechanism to hold decision-makers accountable | A CEO continues risky behaviour unchecked (e.g., Boeing’s 737 MAX crisis). |

| Suppressed Whistleblowing | Fear or retaliation prevents feedback from surfacing | Healthcare workers silenced over unsafe practices. |

| Misaligned Incentives | Rewards reinforce harmful behaviours | Sales teams rewarded for numbers, not ethics (e.g., NAB mortgage brokers. Royal Commission on Banking and Finance). |

| Distorted Information Flow | Data manipulation obscures reality | Volkswagen emissions scandal, where reporting was falsified. |

Table 3: Typology of Dysfunction from Missing Feedback Loops

Example

Case Study: The Robodebt Scandal as a Failure of Feedback Loops in a Complex Adaptive System

The Robodebt scandal in Australia is a stark example of what happens when feedback loops in a complex system break down. The scheme, which relied on an automated algorithm to detect welfare overpayments, ended up issuing thousands of incorrect debt notices to vulnerable Australians. But this wasn’t just a technical failure, it was a systemic breakdown, exposing deep flaws in ethics, governance, and accountability. The absence of effective checks and balances allowed the problem to escalate, with devastating consequences. Rick Morton’s Mean Streak (2024) provides a detailed analysis of these failures.

1. Understanding Robodebt as a Complex Adaptive System Failure

Robodebt was implemented in a public sector system with multiple interacting components, including policy-makers, bureaucrats, automated systems, oversight bodies, and citizens. Ideally, balancing feedback loops (such as legal oversight, public accountability, and organisational learning) would have corrected errors before harm was done. Instead, these loops failed or were bypassed, leading to disastrous consequences.

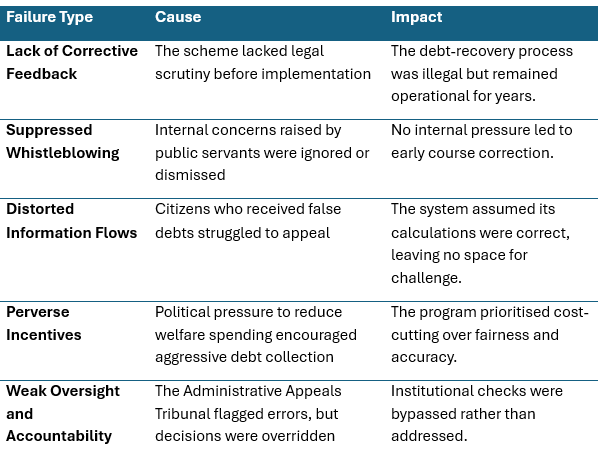

2. Key Missing or Weakened Feedback Loops

Table 4. Typology of missing or weakened feedback loops and their impact.

3. Applying the Viable systems models Viable System Model (VSM) would identify systems failure at three levels.

- System 3 (Operational Oversight) failed: The system assumed automation was infallible and provided no human checks.

- System 4 (External Adaptation) ignored citizen complaints and media reports, failing to adapt to feedback.

- System 5 (Ethical and Strategic Governance) was compromised by political priorities, overriding justice concerns.

Key Takeaways

Organisational dysfunction and ethical failures often stem from a lack of effective checks and balances. Cybernetics and the Viable Systems Model show us that for a system to remain healthy and resilient, it needs strong structures, open information flows, and a culture of continuous learning. Without these, ethical lapses and other forms of ‘drift’ can go unnoticed, and dysfunction can take root.

To prevent this, leaders can:

- Strengthen feedback loops by fostering independent ethics reviews and open reporting channels.

- Promote transparency and accountability through regular audits and robust whistleblower protections.

- Encourage deeper learning, so teams don’t just address surface-level issues but also challenge the assumptions driving them.

- Follow through on integrity, ensuring that ethical breaches have real consequences, not just words on a policy document.

References

- Beer, S. (1972). Brain of the Firm. Allen Lane.

- Beer, S. (1985). Diagnosing the System for Organizations. John Wiley, London and New York

- Davies, D, (2024). The Unaccountability Machine. Profile Books.

- Joyner, K. (2025) Systems thinking for leaders. A practical guide to engaging with complex problems. Queensland University of Technology. https://qut.pressbooks.pub/systemcraft-systems-thinking/

- Morton, R. (2024). Mean Streak: A moral vacuum and a multi-billion-dollar government shake down. Fourth Estate

- Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. MIT Press.