6 Introduction to Systems Inquiry

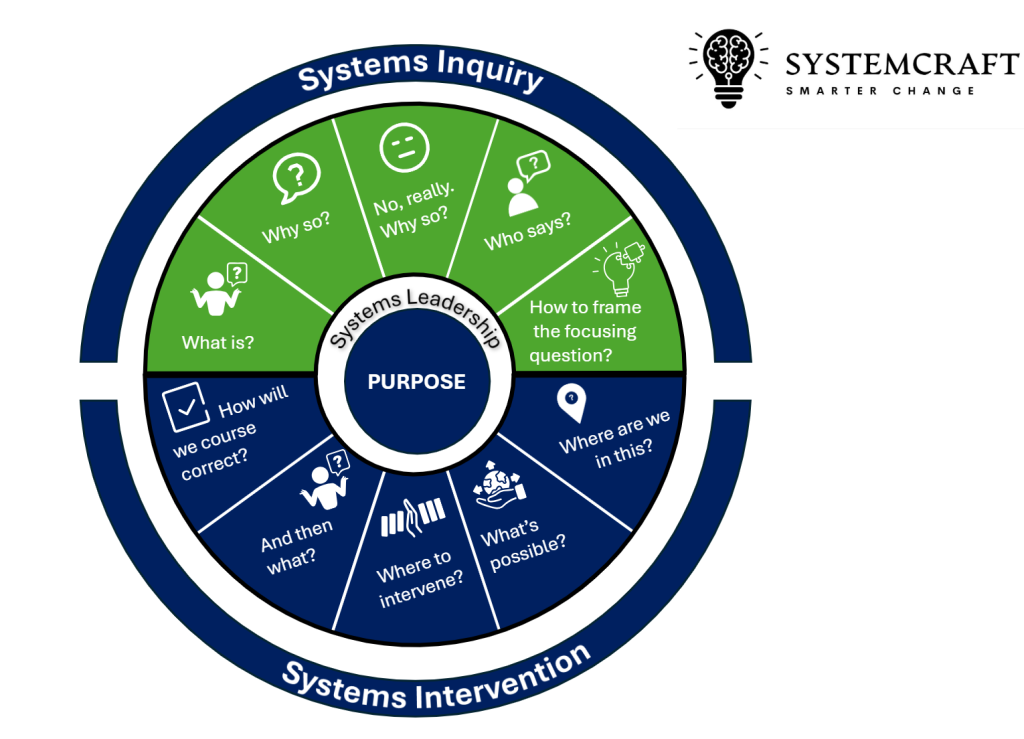

Figure 2. Systemcraft. Systems Inquiry. Joyner (2025)

Introduction to Systems Inquiry

This chapter introduces the Systems Inquiry process and outlines its core components: What is? Why so? No, really, why so? Who says? and How to frame the focusing question? These five elements structure a rigorous approach to investigating systems, ensuring that interventions are guided by a deep and reflexive understanding of the system in focus.

What is? – Defining the System in Focus

The first step in Systems Inquiry is defining What is?; establishing the system in focus. Systems are not self-evident; they must be framed and delineated based on perspective and purpose. This step involves identifying the key structures, actors, processes, and dynamics that constitute the system. Snowden’s Cynefin (2002) model is a useful tool at this stage, helping to classify the nature of the system—whether it is ordered (clear or complicated), complex, or chaotic. At this stage, boundary-setting is crucial, as different boundary choices highlight different aspects of the problem. Jackson’s System in Focus approach within Critical Systems Practice provides a helpful lens for this exercise, ensuring that what is included and excluded in the system definition is an explicit and considered choice.

Why so? – Exploring Commonly Accepted Narratives

Once the system is defined, we ask Why so? interrogating the dominant explanations for why things are the way they are. Systems tend to perpetuate themselves through reinforcing narratives that shape both understanding and action. Often, these explanations appear so self-evident that they go unquestioned, yet they may obscure deeper structural or systemic factors. For example, the narrative that young people struggle to buy homes due to personal financial mismanagement is a common simplification that neglects broader systemic issues such as housing policy, financial markets, and intergenerational wealth disparities. This stage requires identifying dominant perspectives and challenging them with alternative ways of seeing the issue.

No, really, why so? – Digging Deeper

Challenging dominant narratives leads to the next stage of inquiry: No, really, why so? This is where we push beyond surface-level explanations to uncover structural, historical, and cultural drivers of the problem. This deeper level of inquiry is essential to avoid superficial and unsustainable solutions. It requires examining power dynamics, historical trajectories, incentive structures, and unintended consequences of past decisions. Systems thinkers often employ tools such as causal loop diagrams or Meadows’ (1999) leverage points to explore systemic influences and identify where interventions might have the greatest impact. The key here is resisting the temptation of the first plausible explanation and instead pursuing a more layered and interconnected understanding.

Who says? – Evaluating Perspectives and Power in Knowledge

All systems are seen through a lens, and that lens is shaped by who is doing the seeing. Who says? interrogates whose voices shape our understanding of the system and whose perspectives might be missing or marginalised. Knowledge is not neutral; it is situated within power structures, cultural assumptions, and institutional interests. This stage requires examining who constructs dominant narratives and whether alternative voices, such as lived experience, Indigenous knowledge systems, or frontline workers, offer different insights. The aim is to cultivate epistemic humility: recognising that no single perspective holds the complete truth, and that robust systems inquiry must incorporate multiple viewpoints to construct a richer and more inclusive understanding.

How to Frame the Focusing Question? – Refining the Inquiry for Action

The final component of Systems Inquiry is How to frame the focusing question? Inquiry is most powerful when guided by well-crafted questions that illuminate new insights and possibilities. A poorly framed question can reinforce existing assumptions, whereas a well-framed one can open up new ways of thinking. Good questions challenge taken-for-granted understandings, prompt fresh perspectives, and create space for reimagining solutions. This section explores techniques for crafting questions that enhance inquiry, ensuring that systems interventions are informed by meaningful and generative lines of investigation.

Conclusion

Systems Inquiry is not just a method; it is a mindset; one that resists simplistic explanations, embraces complexity, and values multiple perspectives. Each component of this inquiry process serves to deepen understanding and refine the way we approach systemic challenges. By engaging rigorously with What is? Why so? No, really, why so? Who says? and How to frame the focusing question? leaders and decision-makers can develop interventions that are thoughtful, context-sensitive, and ultimately more effective. The following chapters will delve into each of these components in greater detail, equipping readers with the concepts and tools to conduct meaningful systems inquiry in their own contexts.

References

- Joyner, K. (2025) Systems thinking for leaders. A practical guide to engaging with complex problems. Queensland University of Technology. https://qut.pressbooks.pub/systemcraft-systems-thinking/

- Snowden, D. J. (2002). Complex acts of knowing: Paradox and descriptive self‐awareness. Journal of Knowledge Management, 6(2), 100-111.

The ability to critically examine one’s own beliefs, assumptions, and actions, and how they influence and are influenced by the surrounding system or context.