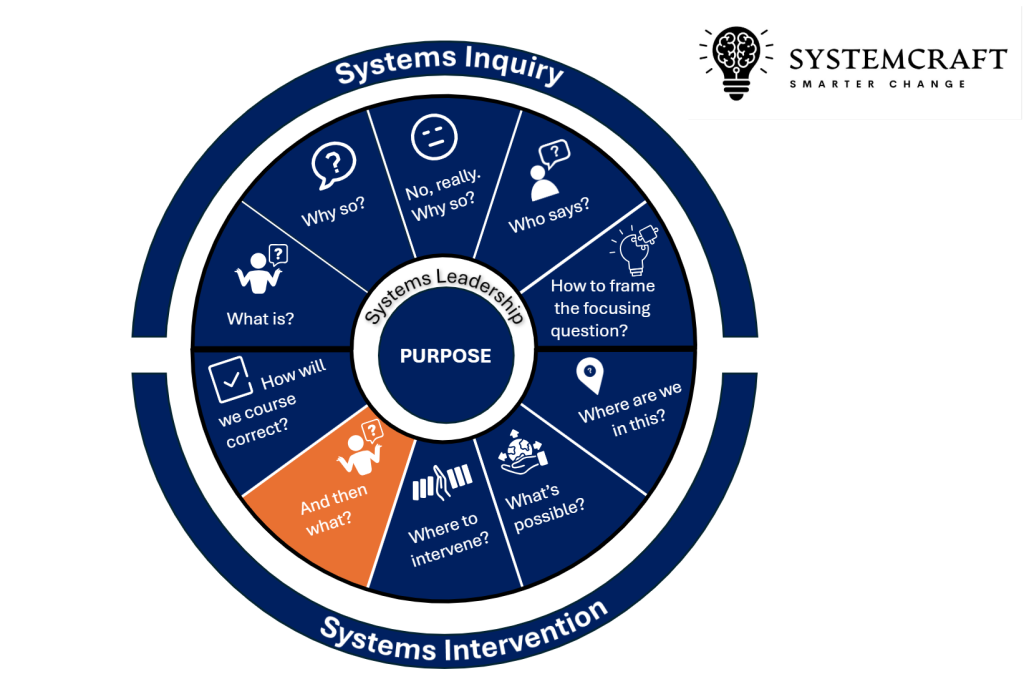

17 And then what?

Figure 14. Systemcraft. And then what? (Joyner, 2025)

Considering the downstream and longer-term impacts of our proposed intervention.

In the Systemcraft framework, the question ‘And then what? plays a critical role in shaping effective interventions within complex systems. It compels leaders to think beyond immediate outcomes and consider the broader, long-term implications of their actions. This perspective ensures a forward-thinking mindset, crucial for identifying second- and third-order effects, anticipating unintended consequences, and fostering long-term system resilience.

Reflexivity and “Where Are We in This?”

Critical systems thinking reminds us that every intervention is shaped by the assumptions, biases, and positions of the intervener. Reflexivity, the practice of questioning our own roles and influences, is a cornerstone of effective systems leadership. As explored in Where Are We in This? understanding our place within the system ensures we do not perpetuate existing power dynamics or reinforce systemic inequities. Reflexivity also illuminates blind spots that might lead to unintended consequences, encouraging thoughtful and equitable interventions.

Anticipating Second- and Third-Order Effects

Interventions often focus on addressing immediate, visible problems, but every action creates ripples that extend far beyond the initial impact. Identifying second- and third-order effects involves examining the cascading consequences of an intervention. For example, implementing a new technology system in an organisation might seem like an effective way to improve efficiency, but without proper training and support, it could lead to employee frustration, decreased morale, and reduced productivity.

A classic illustration of unintended consequences is a leadership team centralising decision-making to improve consistency. While the goal may be increased control, it can inadvertently stifle innovation, demotivate employees, and create bottlenecks in decision-making. These outcomes emphasise the importance of rigorous scenario planning to predict and mitigate negative downstream effects. By examining the ‘And then what?’ question, leaders can better prepare for the complexities of systemic change.

The Long-Term View

Complex systems require interventions framed as long-term ventures rather than short-term projects. Ashton (2023) highlights that organisational crises often take years to develop, requiring a similarly extended period to stabilise and move toward sustainable equilibrium. This mindset challenges the ‘quick fix’ mentality often seen in high-pressure situations.

Consider a corporate restructuring initiative: while it might address immediate financial pressures, failing to account for cultural integration and employee engagement can lead to long-term dysfunction and decreased organisational loyalty. Effective interventions require sustained engagement to foster systemic resilience and prevent cycles of instability.

The Role of Systems Archetypes

Systems archetypes provide valuable insights into recurring patterns; they are a short-hand for leaders considering what effect an intervention may have. However, they also simplify complex realities. While useful, leaders must balance these simplified models with a nuanced understanding of the system’s unique context, history, and stakeholder dynamics. A more detailed explainer on Systems Archetypes and high level considerations for intervening can be found in Kim (2000).

Tool – Systems Archetypes

- Burden to the Intervener: External interventions often create dependencies by addressing immediate issues without empowering local systems. For example, bringing in a specialised project team to resolve a crisis might solve the problem temporarily but leave the organisation reliant on external expertise. Sustainable interventions prioritise building internal capacity and autonomy.

- Shifting the Burden: Short-term fixes often address symptoms while neglecting root causes. For example, relying on external consultants for organisational change might yield temporary improvements but prevent long-term adaptive capacity. Leaders should focus on root-cause analysis to strengthen systems over time.

- Fixes That Fail: Some solutions create new problems or exacerbate the original issue. A common example is offering employee bonuses to improve performance. While this might work initially, it can lead to unhealthy competition, burnout, or a sole focus on metrics at the expense of collaboration and quality. Thoroughly testing interventions for unintended consequences is vital.

- Limits to Growth: Initial success often encounters systemic constraints. For instance, a company might expand rapidly to capture market share, only to find that operational inefficiencies and poor communication undermine its ability to scale effectively. Leaders must anticipate limits and invest in capacity-building to sustain progress.

- Success to the Successful: Feedback loops can amplify inequalities. For example, high-performing teams within an organisation may receive more resources and visibility, which can inadvertently marginalise other teams and create resentment. Recognising such dynamics helps leaders design interventions promoting equity and balance.

Ethical Considerations in Intervention

Before intervening, leaders must ask critical ethical questions: ‘Should we intervene at all?’ and ‘What are the moral responsibilities of our involvement?’ Without understanding systemic dynamics or consulting stakeholders, interventions risk causing harm, perpetuating inequities, or creating dependencies. Ethical interventions require inclusivity, transparency, and accountability to ensure alignment with the public interest and systemic well-being.

Beyond ‘One-Off’ Interventions

Interventions should not be seen as discrete events but as part of an ongoing process. Leaders must ask: What legacy will our actions leave? Will the system be more resilient, equitable, and functional as a result of our involvement? Leaving a weakened system creates more risks than benefits and diminishes trust in future efforts.

This principle applies universally, from organisational reforms to corporate change initiatives. Whether addressing workforce dynamics or implementing new operational processes, the absence of a sustainable plan can lead to wasted investments and eroded trust.

The Path Forward

The question “And then what?” is a vital guidepost for systems leaders. By adopting a long-term perspective, recognising the limitations of archetypes, and addressing the ethical implications of intervention, leaders can navigate complexity more effectively. Reflexivity, as discussed in Where Are We in This? ensures leaders remain mindful of their influence and biases. In a world where the stakes of intervention are higher than ever, this mindset is not optional, it is imperative.

Example

Case Illustration: The Queensland Health Payroll Disaster—Asking ‘And Then What?’ (Queensland Government, 2013)

In 2010, Queensland Health attempted to implement a new payroll system, replacing its outdated legacy system with an SAP-based solution delivered by IBM. The project was meant to streamline payroll processing for 78,000 health workers and improve efficiency. However, what followed was one of the most catastrophic IT failures in Australian public sector history, costing over $1.2 billion and causing widespread financial hardship for employees.

At the heart of the failure was a fixation on meeting implementation deadlines rather than ensuring a functioning and resilient system. By applying Systemcraft’s ‘And Then What?’ question, we can explore how short-term incentives, a lack of reflexivity, and failure to anticipate second- and third-order effects contributed to this disaster.

Immediate Intervention: Rushed Deployment Over System Readiness

The payroll system was fast-tracked under political and managerial pressure to meet a ‘Go Live’ deadline. The project team faced strong incentives to deliver on time, including performance bonuses for key stakeholders involved in project delivery.

The underlying assumption: Once the system goes live, payroll will function as expected, and any issues will be minor.

Second- and Third-Order Effects: What Went Wrong?

1. Fixes That Fail: ‘Go Live’ at All Costs Over Functional Readiness

Despite internal concerns that the system was not yet stable, leaders pushed forward to meet the deadline. As a result:

- Thousands of Queensland Health staff were underpaid, overpaid, or not paid at all.

- Payroll staff had no effective way to rectify errors, leading to manual workarounds that further compounded the chaos.

- Many nurses, doctors, and frontline staff were financially devastated, some taking out loans to cover unpaid wages.

🚨 And then what?

- Instead of improving efficiency, the new system created an operational crisis, requiring emergency teams and manual interventions.

- The government had to spend hundreds of millions in remediation, far exceeding the original project budget.

- Trust in Queensland Health leadership and government IT projects collapsed.

2. Shifting the Burden: Short-Term ‘Go Live’ Success Over Sustainable System Performance

The project’s success was measured by deployment, not by how well the system actually worked. This created a fundamental misalignment between project objectives and operational realities.

- End users (payroll staff and employees) were not properly trained before launch, causing confusion and errors.

- The system lacked customisation for Queensland Health’s complex award structures, meaning payroll calculations were frequently incorrect.

- Ongoing fixes and rework became the new normal, draining resources that could have been spent on improving healthcare services.

🚨 And then what?

- The failure locked the organisation into a cycle of firefighting, consuming years of effort and billions of dollars in damage control.

- Instead of empowering payroll teams, the system created dependence on costly consultants and manual interventions.

3. Limits to Growth: Scaling a System Without Building Capacity

The assumption was that once the system was live, it would handle payroll seamlessly. However, Queensland Health’s payroll requirements were far more complex than initially assumed, and the new system was not equipped to handle the scale.

- The project failed to properly map payroll conditions, leading to tens of thousands of payroll errors.

- The lack of stress-testing and phased rollout meant that failures affected all employees at once, rather than being identified in a controlled pilot.

🚨 And then what?

- The system became an operational liability, and fixing it required more investment than building a new one from scratch.

- Instead of achieving its intended efficiencies, the payroll system became one of the most expensive IT failures in Australian history.

A Better Approach: Incentivising Sustainable Success

Instead of focusing on hitting a ‘Go Live’ deadline, Queensland Health could have:

- Tied incentives to post-Go Live system stability and payroll accuracy, not just deployment.

- Implemented a phased rollout, allowing time for testing, adaptation, and training.

- Built feedback loops into project governance, ensuring stakeholder concerns were heard and acted upon.

- Invested in long-term capability building, rather than relying on external consultants for crisis management.

Final Reflection: Beyond the ‘Go Live’ Fallacy

Queensland Health’s payroll disaster illustrates why leaders must move beyond transactional project metrics and ask:

- What happens after launch?”

- Are we incentivising short-term success at the expense of long-term resilience?

- Are we addressing root causes, or just shifting the burden?

The Queensland Health case is a stark reminder that in complex systems, rushing to deployment without considering ‘And Then What?’ can cause catastrophic failures that take years to repair.

Key Takeaways

Practical Steps for Systems Leaders

- Map consequences, using tools like causal loop diagrams or scenario planning to visualise potential ripple effects.

- Adopt a long-term horizon by framing interventions with timelines that match the system’s complexity.

- Plan for resilience by ensuring interventions strengthen the system’s capacity to manage future challenges.

- Engage diverse perspectives by including a range of stakeholders to uncover blind spots and prevent unintended consequences.

- Commit to follow-through by designing interventions with clear plans for sustained governance and adaptation.

References

- Ashton, C. (2023) And then what? Inside stories of 21st century diplomacy. Elliott and Thompson.

- Joyner, K. (2025) Systems thinking for leaders. A practical guide to engaging with complex problems. Queensland University of Technology. https://qut.pressbooks.pub/systemcraft-systems-thinking/

- Kim, D. (2000). Systems Archetypes: Diagnosing systemic issues and designing interventions – the Systems Thinker. The Systems Thinker. https://thesystemsthinker.com/systems-archetypes-i-diagnosing-systemic-issues-and-designing-interventions

- Queensland Government. (2013). Queensland Health Payroll System Commission of Inquiry Report. The Honourable Richard Chesterman AO RFD QC. Retrieved from https://cabinet.qld.gov.au/documents/2013/aug/health%20payroll%20response/Attachments/Report.pdf

- Senge, P. M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. Doubleday.

Second-order effects are the indirect consequences or outcomes of an action or event, resulting from its immediate impacts.

Third-order effects are the subsequent ripple effects that arise from the second-order effects, often more complex and harder to predict.

Both terms highlight the cascading impact of decisions and events in systems.

Outcomes of an action or decision that were not anticipated or intended, which can be positive, negative, or neutral, often arising due to the complexity of systems

A system's ability to absorb shocks, adapt to changing conditions, and recover from disruptions while maintaining its core functions, purpose, and structure.

The ability to critically examine one’s own beliefs, assumptions, and actions, and how they influence and are influenced by the surrounding system or context.

Systems archetypes are recurring patterns of behaviour in complex systems that help explain and predict how system structures drive outcomes. They provide insights into underlying dynamics, enabling more effective interventions.

Although found in several texts, the range of archetypes can be found in Senge, P. M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. Doubleday.