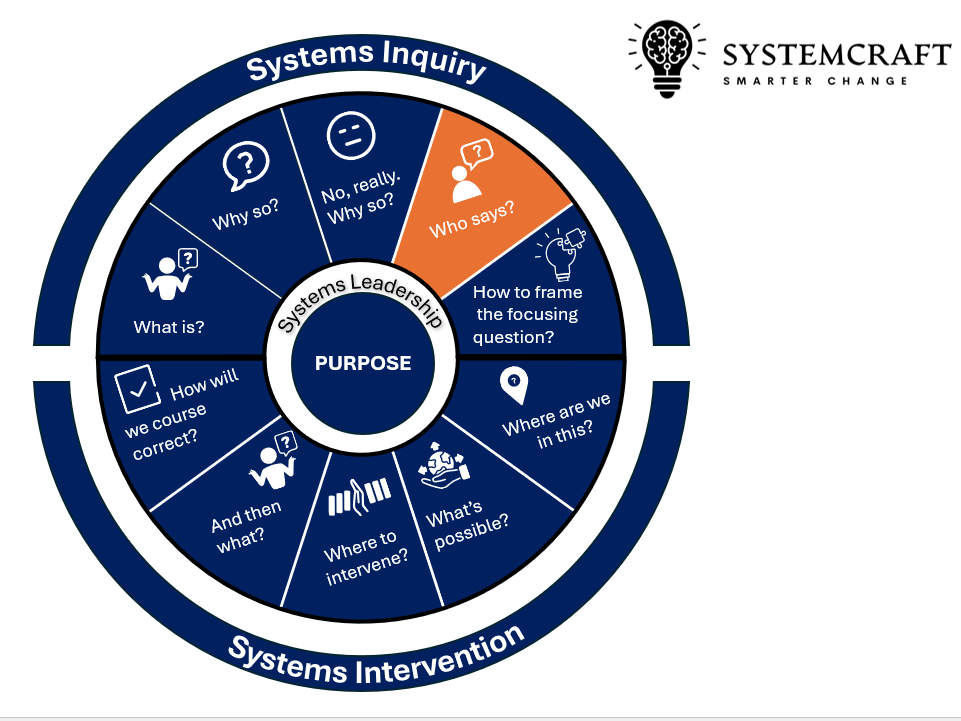

10 Who says?

Figure 7. Systemcraft – Who Says? (Joyner, 2025)

Identifying whose voices and interests are privileged in the way the issue is spoken of, analysed and actioned.

In the messy, entangled world of complex problems, it can seem like we only see the system through a single lens, the loudest voices or the most dominant perspectives. But systems are (largely) made up of people, each with their own perspectives, worldviews, and experiences. If we want to truly understand the system, we need to understand all the voices within it, not just the powerful or the powerless, but everyone who shapes, navigates, and experiences the system in their own way.

The No Really, Why So? step in Systemcraft explores what we think we see in any given situation. The “Who Says?” stage of Systemcraft encourages systems thinkers to pause and ask: How do different people in this system see and understand the issue? This step helps us surface the assumptions we are making, where the power lies in the system and provides a richer, more complete understanding of the system, its dynamics, and its possibilities.

The idea of perspective is explored, followed by two sensemaking tools are explored in this chapter. Each emerges from the Critical Systems Thinking paradigm.

Example

If we’re looking at a health system, policymakers may focus on budgets and performance metrics. Doctors might see the system through the lens of clinical practice and patient care. Patients and their families bring their lived experiences of waiting, access, and outcomes. Each of these perspectives is valid, but none of them tells the whole story.

Understanding the system means understanding how and why different people see it the way they do.

Ukiyo-e print illustration from Buddhist parable. Each man reaches a different conclusion based on which part of the elephant he has examined. (“Blind monks examining an elephant” by Itcho Hanabusa (1888). Library of Congress. The image is dedicated to the public domain under CC0.)

Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) – Peter Checkland (1990)

SSM is a structured approach to tackling complex, ill-structured problems; situations where multiple perspectives exist, and there is no single, clear solution. Unlike hard systems approaches, which assume problems can be objectively defined and solved, SSM acknowledges that problems are socially constructed and shaped by different stakeholders’ worldviews.

SSM involves seven iterative stages, including exploring the problem situation, developing conceptual models, and testing these against real-world perspectives. A critical aspect is ‘Weltanschauung’ (worldview), the recognition (as above) that how a problem is framed depends on the perspective of those involved. You can find an explainer video on SSM here.

Relevance to “Who Says” in Systemcraft:

- SSM reminds us that any claim about a system’s problems, causes, and solutions is shaped by who is making the claim.

- It urges us to surface and challenge dominant assumptions about ‘the way things are.’

- SSM provides tools for mapping stakeholder perspectives, helping identify whose views are influencing decision-making and whose are ignored.

Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH) – Werner Ulrich (1983)

CSH is a framework for evaluating the validity and fairness of system designs and interventions by questioning who controls and benefits from them. Ulrich argued that every system operates within boundaries of knowledge and power, and these boundaries determine what is considered ‘relevant’ or ‘valid’ knowledge. An explainer video may help.

CSH introduces 12 boundary questions, which probe:

- Who defines the system’s purpose?

- Who controls resources and decision-making?

- Who benefits and who is left out?

- What assumptions underpin these definitions?

These questions expose hidden biases in decision-making and reveal whose interests are being privileged or marginalised.

Relevance to “Who Says” in Systemcraft:

- CSH reinforces the need to interrogate power and legitimacy—not just ‘what is being said’ but who is in a position to say it.

- It encourages boundary critique—questioning who gets to frame a problem, whose knowledge counts, and who is excluded.

- It aligns with Systemcraft’s call to examine dominant narratives and challenge taken-for-granted definitions of system purpose and effectiveness.

Bringing Them Together in “Who Says”

Both SSM and CSH highlight that system definitions, problems, and solutions are not neutral—they are shaped by stakeholder interests, power dynamics, and worldviews.

- SSM helps explore competing perspectives and how different actors construct the system differently.

- CSH provides a critical lens to examine who holds decision-making power, whose knowledge is validated, and who is marginalised in system conversations.

In Systemcraft, this means:

- Scrutinising who gets to frame the problem.

- Surfacing implicit assumptions about ‘the system’ and its goals.

- Examining how systemic interventions serve some groups while disadvantaging others.

The “Who Says” chapter should prompt leaders and systems thinkers to question dominant narratives, map stakeholder interests, and actively engage with marginalised perspectives to craft more just, effective, and inclusive system interventions.

Expanding Worldviews to Unlock Change

When we take the time to surface and engage with multiple perspectives, we create new possibilities for understanding and change. Seeing the world through another’s eyes can challenge our assumptions, expand our thinking, and unlock new ways of intervening in the system.

Consider a community dealing with rising homelessness. Policymakers may frame the issue around housing supply. Social workers might focus on addiction or mental health services. People experiencing homelessness may see barriers to accessing support, a lack of dignity, or systemic discrimination. All of these perspectives are part of the system, and only by understanding them together can we address the issue effectively.

A Practice for Systems Thinkers

Engaging with multiple perspectives doesn’t mean we need to agree with all of them, but it does mean we need to take them seriously. Here are three simple practices to bring into your systems work:

- Map the perspectives. Who are the key groups in the system? How does each group see the issue? What shapes their worldview?

- Ask Ulrich’s questions. Whose voices are framing the problem? Who is excluded? What assumptions are at play?

- Seek to understand, not judge. Be curious about how and why different people see things differently. What insights do their perspectives offer?

By taking the time to understand the diverse perspectives within a system, we see not just the problem, but the system itself more clearly. We build a more inclusive, nuanced, and actionable understanding of the issue, one that opens up new pathways for change.

Examples: Applying the SSM and CSH Tools: The Case of Juukan Gorge

Here’s an illustration of Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) and Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH) applied to the Juukan Gorge destruction by Rio Tinto, highlighting how both approaches can interrogate who had the power to frame the issue, whose voices were prioritised, and whose perspectives were excluded. Research from Oliveri, Porter, Davies & James (2024).

Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) – Mapping Perspectives on Juukan Gorge

1. Problem Situation (Unstructured):

The destruction of Juukan Gorge in 2020 by Rio Tinto sparked outrage due to its immense cultural significance to the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura (PKKP) peoples. The decision to proceed with the blast was legally sanctioned but ignored Indigenous voices.

2. Key Stakeholders and Their Worldviews (Weltanschauung):

- Rio Tinto Executives: Framed the site as a legal mining operation, prioritising economic value and shareholder returns.

- PKKP Traditional Owners: Saw Juukan Gorge as a sacred site, integral to cultural identity and historical continuity.

- Australian Government Regulators: Tended to prioritise industry interests under outdated heritage protection laws.

- Investors and Shareholders: Initially focused on economic benefits, but later some pushed for accountability after the destruction caused reputational damage.

- Public and Media: Reacted strongly post-destruction, shifting the framing towards corporate accountability and Indigenous rights.

3. Conceptual Models:

- A heritage-first model (valuing cultural sites over profit).

- A corporate governance model (prioritising fiduciary duties).

- A negotiated power-sharing model (joint decision-making with Traditional Owners).

4. Testing Against Reality:

Rio Tinto’s decisions revealed asymmetry in power—legal structures favoured mining, and the PKKP’s concerns were ignored despite clear opposition.

5. Identifying and Implementing Change:

Post-destruction, Rio Tinto’s leadership faced scrutiny, leading to executive resignations and changes in policy. However, SSM shows that without structural change to heritage laws and corporate governance, similar incidents could recur.

Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH) – Examining Boundaries of Power and Knowledge

CSH helps expose who had the authority to define the system and who was excluded. Below is how Ulrich’s boundary questions apply to Juukan Gorge.

| CSH Boundary Question | Application to Juukan Gorge |

|---|---|

| Who defines the system’s purpose? | Rio Tinto, under a corporate profit-driven model, with minimal consideration of cultural heritage. |

| Who has decision-making control? | Rio Tinto executives and legal frameworks biased towards mining. Traditional Owners had consultation rights but no veto power. |

| Who benefits? | Shareholders and executives through increased iron ore revenue. |

| Who is affected but lacks control? | The PKKP peoples, who lost an irreplaceable sacred site. |

| What knowledge is considered valid? | Economic and geological data. Indigenous cultural and historical knowledge was largely dismissed. |

| What voices are excluded? | Traditional Owners’ opposition was acknowledged but ultimately ignored. |

| What assumptions shape the system? | That economic gain outweighs cultural loss; that legal compliance equates to ethical responsibility. |

| What alternative boundaries could be drawn? | Placing Indigenous cultural heritage protection on equal footing with economic interests. |

| Who should have a greater say? | The PKKP peoples, whose deep cultural ties to the land were overridden. |

| What should count as success? | Not just profit but preserving cultural heritage alongside economic development. |

Table 2: Critical Systems Heuristics applied to Juukan Gorge case

Bringing It Together in “Who Says?”

- SSM highlights the competing worldviews at play, showing how the system’s structure privileged mining interests.

- CSH exposes the power dynamics, revealing who had the authority to make decisions, whose knowledge was deemed legitimate, and whose voices were ignored.

This case demonstrates how system boundaries were drawn to exclude Indigenous authority, and Systemcraft must challenge these exclusions by asking:

- Who is defining the problem and the ‘solution’?

- Whose interests are embedded in the system’s design?

- What assumptions shape the narratives of legitimacy and authority?

By using SSM and CSH we can identify systemic inequities and propose ways to rebalance power in decision-making.

Key Takeaways

Here are five key learning takeaways from the chapter:

- Systems Are Shaped by Perspectives and Power Dynamics

Every system is viewed differently by those within it; leaders, frontline workers, policymakers, and communities each bring distinct worldviews. Recognising how perspectives shape problem definitions and decision-making is crucial to understanding a system holistically. - Unpacking Dominant Narratives Through Systemcraft

The “Who Says?” stage in Systemcraft encourages questioning whose voices frame an issue, whose knowledge is legitimised, and whose perspectives are excluded. This step helps reveal hidden assumptions, power imbalances, and alternative ways of defining the system. - Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) Helps Map Multiple Perspectives

SSM provides a structured way to explore different stakeholders’ worldviews, highlighting how problems are socially constructed rather than objectively defined. By using SSM, systems thinkers can identify conflicting perspectives and seek more inclusive approaches. - Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH) Exposes Power and Exclusion

CSH encourages boundary critique by asking who controls resources, benefits from decisions, and defines what counts as valid knowledge. Applying CSH reveals systemic biases, helping leaders challenge inequities and expand the boundaries of consideration.

References

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge University Press.

- Checkland, P., & Scholes, J. (1990). Soft systems methodology in action. Wiley

- Joyner, K. (2025) Systems thinking for leaders. A practical guide to engaging with complex problems. Queensland University of Technology. https://qut.pressbooks.pub/systemcraft-systems-thinking/

- Oliveri, V. A., Porter, G., Davies, C., & James, P. (2024). The Juukan Gorge destruction: a case study in stakeholder-driven and shared values approach to cultural heritage protection. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 14(6), 919–933

- Ulrich, W. (1983). Critical heuristics of social planning: A new approach to practical philosophy. Haupt.

Critical Systems Thinking (CST): A reflective and pluralistic approach to understanding and intervening in complex systems. CST integrates multiple systems methodologies to address power dynamics, conflicting perspectives, and ethical considerations. It emphasises boundary critique, questioning who defines the system, whose knowledge is privileged, and whose interests are marginalised—to ensure more just and effective interventions.