8 Why so?

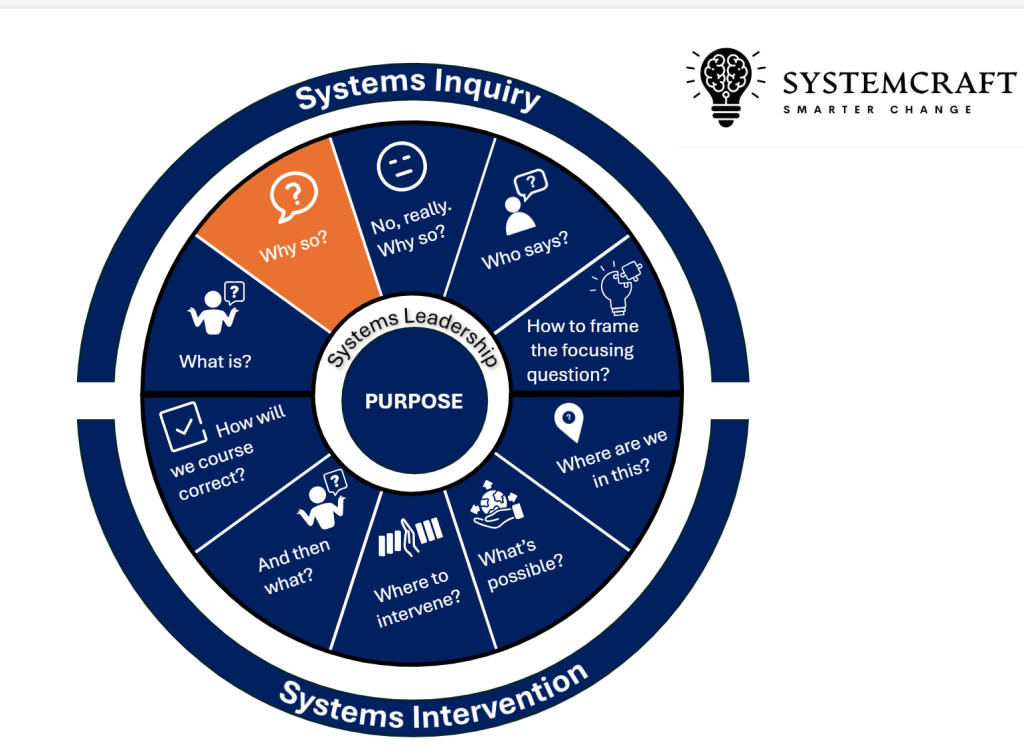

Figure 4. Systemcraft. Why So? (Joyner, 2025)

Surfacing and challenging the usual explanations and narratives for this problem situation.

Round up the usual suspects

When we start inquiring into issues and problems, we meet with the well-worn explanations for complex societal and organisational issues. At the societal level, consider the struggle of young people to buy homes, a challenge often framed as the result of a profligate lifestyle and a lack of saving discipline (anyone for smashed avo?). At the organisational level, management often reacts to a decline in employee productivity with a stronger enforcement of performance management, without exploring what may be more structural conditions that shape productivity.

‘Why so?’ pushes past cognitive biases.

This tendency to quickly label and react can be a result of availability bias. In the organisational example, leaders easily recall anecdotes of individual underperformance rather than taking the time to analyse systemic trends. In the housing case, the ‘smashed avo’ became a well-recognised meme that we all easily bring to mind when voicing an opinion about the first home buyer.

A key insight from Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011) is that many of these dominant narratives persist because they are products of this type of System 1 thinking; fast, intuitive, and often biased.

Kahneman’s dual-system model explains how people process information and make decisions:

Subvert the dominant paradigm, resistors!

The Why So? phase of Systemcraft functions as an intervention, prompting System 2 thinking, which is slower, more deliberate, and more analytical. Russell Ackoff’s (1999) concept of challenging dominant problem frames is particularly relevant here. Ackoff argues that the way we frame a problem determines the kinds of solutions we pursue. A frame focused on individual responsibility, as in the housing example, pushes us toward solutions like financial literacy programs. These can be helpful, but they are ultimately limited because they don’t address the systemic issues that shape housing affordability. By challenging this frame, we open ourselves to alternative solutions that address the root causes; affordable housing policies, wage growth initiatives, and financial regulations that foster stability.

References

- Ackoff, R. L. (1999). Re-creating the corporation: A design of organizations for the 21st century. Oxford University Press.

- Joyner, K. (2025) Systems thinking for leaders. A practical guide to engaging with complex problems. Queensland University of Technology. https://qut.pressbooks.pub/systemcraft-systems-thinking/

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Key Takeaways

So why ‘Why so?’

Leaders and policymakers often operate under extreme time pressure, making them susceptible to System 1-driven narratives that oversimplify complexity. Teaching them to use Why So? as a mental discipline helps them recognise when they are relying on fast-thinking biases and engage in deeper structural and systemic analysis that may lead to more sustainable ways forward.

Ultimately, “Why so?” is a call to interrogate the explanations we take for granted. It pushes us to explore alternative frames and encourages a more nuanced understanding of complex problems. By applying this question consistently, systems thinkers can reveal the often-hidden dynamics that keep systems stuck, opening pathways toward more effective, systemic solutions.

A cognitive bias where people overestimate the importance of information that is most readily available to them, such as recent events, vivid examples, or widely publicised stories, rather than considering all relevant data objectively. This can lead to distorted decision-making and reinforce dominant but misleading narratives.