9 No really. Why so?

Figure 5. Systemcraft – No really. Why So? (Joyner, 2025)

Getting beneath the surface, or simplistic explanations to examine structural and cultural explanations for the behaviour of systems.

The previous chapter (‘Why so?’) argued that as a systems thinker we need to surface and challenge the dominant explanations for complex issues, both societal and organisational. By applying this question consistently, systems thinkers can reveal the often-hidden dynamics and structures that keep systems stuck, opening pathways toward more effective, systemic solutions.

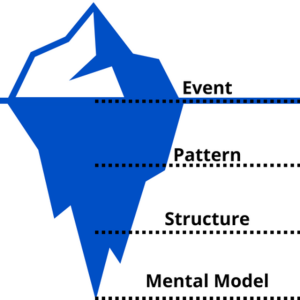

The No Really. Why so? question takes us into the analysis that will reveal those hidden dynamics and structures. The Iceberg model (attributed to Fechner, 1860) is our scaffold, including events, patterns, structures and mental models. Once into structural elements of systems we consider both Critical Systems Thinking and Systems Dynamics analyses, as outlined in Chapter 2 Core Paradigms.

Iceberg Model

The Iceberg Model (att: Fechner, 1860) is a systems thinking framework used to analyse complex issues by examining different levels of causality beyond visible events. It helps uncover the deeper structures and assumptions that sustain systemic problems. The model consists of four levels:

- Events (Surface-Level Symptoms). The immediate, observable issues that attract attention, such as crises, disruptions, or anomalies.

- Patterns (Trends Over Time). Recurring behaviours and trends that indicate deeper systemic forces at play.

- Structures (Systemic Causes) The underlying policies, rule, incentives, regulations, power dynamics, and institutional frameworks that shape behaviours and outcomes.

- Mental Models (Deeply Held Assumptions and Beliefs). The cultural narratives, ideologies, and worldviews that shape how individuals and societies perceive and respond to issues.

By moving down the iceberg, the model helps shift thinking from reactivity to systems thinking, enabling long-term and sustainable interventions. We will go back to the housing affordability issue as an illustration of the model.

Figure 6: Iceberg Model. From reactivity to systemic responses. (“Iceberg mental model visual representation” by Slade74. The image is dedicated to the public domain under CC0.)

1. Events: The Visible Issues (What We See Above the Waterline)

Examples

The housing affordability is frequently in the public attention. At the surface level, the crisis manifests in several immediate, observable symptoms, including:

- Escalating house prices makes homeownership increasingly out of reach for young people, particularly in Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane, due to soaring property prices.

- Rents have surged, with young renters struggling to secure stable and affordable housing.

- Declining homeownership rates with the proportion of 25–40-year-olds who own a home dropping significantly compared to previous generations.

- High deposit requirements mean many young Australians find it impossible to save for a home deposit due to stagnant wages and rising living costs.

- Increasing reliance on ‘The Bank of Mum and Dad’ with a growing number of first-home buyers depending on family financial support to enter the market.

- Rise in housing insecurity and homelessness with more young Australians are experiencing precarious housing situations; some forced into shared living arrangements or couch surfing.

These symptoms dominate political debates, media discussions, and public concern, but they are the result of deeper systemic forces, which are revealed by going further beneath the waterline.

2. Patterns: Recurring Trends and Behaviours Over Time

As a good systems thinker we 'zoom out' to examine an issue over time for patterns and trends to emerge.

Examples

In the case of housing in Australia, several long-term trends indicate a worsening crisis:

- House prices are outpacing wage growth: Since the 1990s, property values have risen dramatically, while real wages have stagnated, widening the affordability gap.

- Rent increases are outpacing inflation: Rental prices in major cities have consistently grown faster than income levels.

- Property investment by older generations is increasing, with more baby boomers and Gen Xers own multiple investment properties, reducing the stock available for first-home buyers.

- Reduction in social and affordable housing: Government investment in public and social housing has declined, exacerbating the rental market’s pressure.

- Property is increasingly a wealth-building strategy: Housing has increasingly been treated as a financial asset rather than a basic necessity.

- Boom-and-bust housing cycles: Periods of rapid price growth are often followed by brief corrections, but overall affordability continues to decline.

- Policy incentives are benefiting investors over first-home buyers: Tax policies such as negative gearing and capital gains tax (CGT) concessions favour investors, maintaining high property demand and prices.

- Generational divide in homeownership is increasing, with young Australians waiting longer to buy homes, while older generations accumulate wealth through property.

These patterns reflect structural imbalances that sustain the problem in focus.

3. Structural Causes: The Systemic Design That Reinforces the Issues

Beneath these trends lie structural forces that shape outcomes

Examples

- Tax policy is favouring investors with negative gearing and CGT discounts making property investment highly attractive. This leads to speculative buying and inflating house prices.

- Land-use regulations and zoning laws often restrict medium- and high-density developments, limiting housing supply in key urban areas.

- Bank lending practices often prioritise lending to property investors over first-home buyers, contributing to price escalation.

- Government policies have failed to expand public housing at the rate required to meet growing demand.

- Affordable housing is often located in outer suburbs with poor transport links and fewer job opportunities, limiting accessibility for younger workers.

- Foreign buyers, particularly in major cities, have added pressure to housing demand, although recent policy changes have sought to curb this.

- Despite economic growth, real wage increases have lagged behind the rising cost of living, making it harder for young people to save for a home deposit.

- Boomer wealth concentration in housing: Older generations hold a disproportionate share of housing wealth, and intergenerational wealth transfer is uneven, exacerbating inequalities.

These structural issues lock in affordability challenges and reinforce inequalities in access to housing.

These structural issues lock the system into its current equilibrium and make intervention challenging as there are stakeholders who are benefitting from the system in its current state.

4. Mental Models and Assumptions: The Deeply Rooted Beliefs Shaping the System

At the deepest level, mental models and cultural narratives shape policies, public attitudes, and the housing market itself.

Examples

- Homeownership remains the Australian Dream with strong societal expectation that owning property is a marker of success. This reinforces demand for homeownership at all costs.

- Housing is viewed as an investment rather than a social good: The view that property is primarily a wealth-building tool rather than a fundamental right has shaped policies that prioritise market efficiency over affordability.

- “Just Work Harder and Save More”: The belief that young people struggle to buy homes due to lifestyle choices rather than systemic barriers ignores rising house prices, stagnant wages, and growing living costs.

- Political reluctance to regulate the property market stems from the assumption that free-market principles should dictate housing prices and supply.

- Many homeowners assume that passing down property wealth within families is natural and beneficial, despite the growing wealth divide.

- Communities often oppose apartment developments due to concerns about neighbourhood character and property values, limiting the supply of affordable housing.

- Governments often prioritise short-term political gains (e.g., first-home buyer grants) rather than structural reforms that could create long-term affordability.

These deeply ingrained mental models make meaningful reform difficult, as they shape public perception and policymaker priorities. When we go to Systems Intervention, we will see that theorists advocate change at the level of the structures and mental models, in order to effect transformational system change.

POSIWID

When we consider the symptoms our behaviour that a system is consistently producing (in our case rental and home ownership unaffordability) some systems theorists suggests that the system is not broken, it’s producing the outcomes it’s designed to produce. The maxim The Purpose of a System is What It Does (POSIWID) was coined by Stafford Beer (1985), a pioneering figure in cybernetics and systems thinking. Beer used this phrase to emphasise that a system’s actual function and impact, rather than its stated goals or intended purpose, define its true purpose. In other words, the observable outcomes of a system reveal its implicit purpose, regardless of rhetoric or intent.

Examples

A critical systems perspective would suggest, for example, that the actual purpose of the Australian housing system is not to provide affordable housing but to sustain a property investment economy that benefits existing asset holders. They would argue that:

- If housing affordability were truly a priority, we would see falling housing costs, stronger tenant protections, and increased social housing, but we do not.

- If homeownership for young people were a genuine goal, policies would disincentivise speculative investment, but they instead fuel it.

- If housing were viewed as essential infrastructure, planning laws and funding models would prioritise affordable housing construction, but instead, market-driven development dominates.

PSQ: Payoff to the Status Quo

Peter Stroh (2015), a systems thinking practitioner, highlights a crucial insight in the behaviour of systems: systems maintain their current state because key stakeholders benefit (experience payoff) from maintaining the status quo. Even if a system is widely seen as dysfunctional or harmful, certain groups receive advantages, economic, political, or social payoffs, that keep the system locked in place.

Example

In the Australian housing market, despite widespread concern over affordability, powerful stakeholders continue to benefit from the existing system, creating strong resistance to transformative change. Investors enjoy tax benefits. Existing Homeowners (Boomers and Gen Xers) benefit from rising property values, which increase household wealth, enabling homeowners to use real estate for retirement security, investment leverage, or inheritance planning. Banks and Financial Institutions benefit from the mortgage industry, as one of the most profitable sectors.

Proposed reforms (for example changing negative gearing) directly threaten these and other powerful vested interests, making change politically and economically difficult.

In summary, Stroh’s (2015) ‘payoffs to the status quo’ explain why housing affordability remains an intractable problem in Australia, because the existing system benefits powerful stakeholders who resist structural reform. Until these incentives are altered, policies will likely continue to favour investment and wealth accumulation over equitable housing access, leaving younger Australians locked out of homeownership and struggling in a rental market that prioritises profits over people.

CST and SD Comparison

A critical systems thinker and a systems dynamics theorist would approach the No really. Why so? question differently due to their distinct methodologies and underlying assumptions.

Examples

A critical systems thinker (CST), drawing from Critical Systems Practice (CSP), would focus on power structures, inequalities, and underlying ideologies that shape the housing system. They would question who benefits from the current system, expose hidden assumptions, and challenge dominant narratives (e.g., housing as an investment vs. a social good). CST would explore multiple stakeholder perspectives, including renters, Indigenous groups, and low-income earners, and advocate for participatory approaches that empower marginalised voices. They might propose transformative interventions such as rethinking land ownership models, de-commodifying housing, or embedding Indigenous knowledge into urban planning.

A systems dynamics theorist (SDT), influenced by Jay Forrester’s work, would model the feedback loops and delays in housing markets to understand how policy levers (e.g., tax incentives, interest rates, supply constraints) drive price fluctuations. They would use simulation models to predict how interventions (e.g., increasing supply, rent caps) might create unintended consequences. SDT would focus on policy efficiency but may not critically examine social power dynamics or the ethics of market-driven housing.

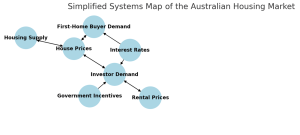

Systems Map: A sensemaking tool

Within the Systems Dynamics paradigm, a systems map is a powerful visual tool used in systems thinking to represent the key elements of a system and their interrelationships. It helps practitioners move beyond linear cause-and-effect thinking to a more holistic understanding of complex issues. By mapping out components, feedback loops, and influences, a systems map reveals structures, dependencies, and leverage points thafeedback loopst may not be immediately obvious.

At its core, a systems map consists of nodes (representing key actors, forces, or variables) and connections (depicting relationships, flows, or causal links). The map may include reinforcing and balancing feedback loops, which highlight how changes within the system can amplify or regulate outcomes over time. Systems maps can take various forms, including causal loop diagrams, stock-and-flow models, and influence maps.

This tool is particularly valuable for problem framing, identifying bottlenecks or unintended consequences, and uncovering hidden dynamics that shape system behaviour. It supports decision-makers in exploring different perspectives, testing potential interventions, and anticipating second-order effects.

By making complex systems visible, systems maps enhance collaborative sense-making, enabling diverse stakeholders to build a shared understanding of challenges and solutions. Whether used in policy, strategy, or organisational change, systems mapping fosters more informed and adaptive decision-making.

Examples

Three key feedback loops:

- House Prices ↔ Investor Demand (Reinforcing Loop)

- Higher house prices attract more investors, expecting capital gains.

- Increased investor demand further drives up prices, making housing less affordable for first-home buyers.

- Investor Demand ↔ Rental Prices (Reinforcing Loop)

- Rising rental prices increase returns for investors, encouraging more property investment.

- Increased investor demand reduces available housing for owner-occupiers, keeping rents high.

- Housing Supply → House Prices (Balancing Loop)

- Increased housing supply can reduce house prices by meeting demand.

- However, construction costs, planning delays, and zoning restrictions slow supply growth, weakening this balancing effect.

Additionally, government incentives (such as negative gearing and tax policies) fuel investor demand, exacerbating the reinforcing loops. Meanwhile, interest rates act as a balancing force, suppressing demand when they rise.

This systemic perspective shows why housing affordability remains challenging—reinforcing loops keep prices high, while balancing loops are weak or delayed.

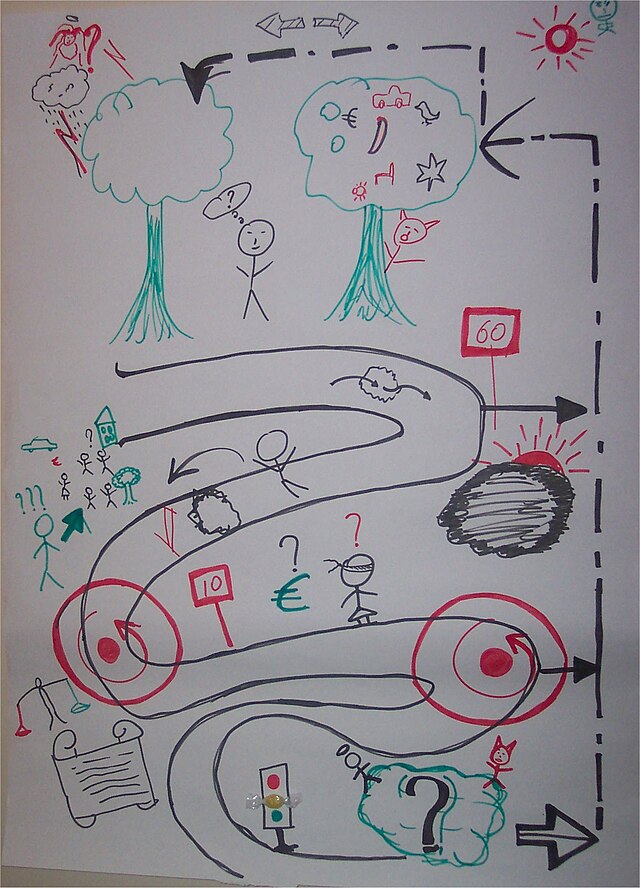

Pushing out your No Really. Why So? Analysis. The Rich Picture

The analyses above each use a slightly different lens and help us see different aspects of our housing problem. They are also very tidy!

When we first seek to explore with other the No really. Why so? question we want to be a bit messier and make sense of our problem with others in a way that allows for free-flowing discussion and mapping of ideas. This process is actually more important than the product produced. Remember that our purpose in Systemcraft is more system-aware organisations and institutions. We do that by sharing our experience of the problem and how we see the system.

Peter Checkland (1990), in his Soft Systems Methodology (SSM), describes rich pictures as a tool for capturing and exploring the complexity of real-world problem situations. He emphasises their utility in problem structuring, sense-making, and engaging multiple perspectives before attempting to analyse or intervene in a system. Checkland highlights that rich pictures are not meant to be precise models but rather informal, intuitive depictions of the messy, human aspects of systems. They allow practitioners to map out key actors, relationships, processes, conflicts, and environmental factors in a way that encourages deeper understanding. This visual representation helps reveal hidden assumptions, power dynamics, and differing stakeholder viewpoints that might not emerge through conventional analysis.

An example of a rich picture is included below, indicating that graphic skill is not the most important element; sharing ideas about interdependencies and systems elements is the point.

Figure x: Rich picture example. (“Example of a Rich Picture: Sustainable Development Indicators in Malta” by Cis98sm. The image is dedicated to the public domain under CC0)

A key benefit Checkland notes is that creating a rich picture forces engagement with complexity rather than reducing it too soon into structured problem definitions. He argues that many organisational problems stem from misaligned perceptions rather than purely technical failures, and rich pictures provide a way to explore these perceptions collaboratively.

Ultimately, in Checkland’s SSM, rich pictures serve as a foundation for dialogue, helping participants externalise their understanding of a situation, leading to better-informed and more inclusive interventions.

Key Takeaways

- Moving Beyond Surface-Level Explanations

The No Really. Why So? approach deepens systems inquiry by challenging dominant explanations and uncovering hidden dynamics. Using the Iceberg Model, systems thinkers move from observable events to deeper structural causes and mental models that sustain systemic issues. - Systems Persist Because They Benefit Certain Stakeholders

The concepts of POSIWID (the Purpose of a System is What It Does) and Payoff to the Status Quo (Stroh, 2015) explain why complex problems persist. The current housing system benefits investors, banks, and existing homeowners, creating resistance to transformative change despite widespread public concern. - Critical Systems Thinking (CST) vs. System Dynamics (SD)

Different systems approaches provide distinct insights. CST focuses on power dynamics, ideology, and stakeholder engagement, advocating for transformational change. SD models policy feedback loops and unintended consequences but may not critically examine inequalities and systemic biases. - Sensemaking and Collective Inquiry Matter More Than “Tidy” Models

Tools like systems maps and rich pictures help visualise complexity, but their real value lies in engaging stakeholders, surfacing diverse perspectives, and fostering systemic awareness within organisations. Checkland’s (1990) Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) encourages capturing real-world complexity before jumping to structured problem definitions.

References

- Beer, S. (1985). Diagnosing the System for Organizations. John Wiley, London and New York

- Checkland, P., & Scholes, J. (1990). Soft systems methodology in action. WileyFechner, G. (1860), Elemente der Psychophysik, vol 2. p.521. in Jones, E., The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, Vol 1, Hogarth Press, 1953, p. 410

- Fechner, G. (1860), Elemente der Psychophysik, vol 2. p.521. in Jones, E., The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, Vol 1, Hogarth Press, 1953, p. 410

- Joyner, K. (2025) Systems thinking for leaders. A practical guide to engaging with complex problems. Queensland University of Technology. https://qut.pressbooks.pub/systemcraft-systems-thinking/

- Stroh, D. P. (2015). Systems thinking for social change: a practical guide to solving complex problems, avoiding unintended consequences, and achieving lasting results. Chelsea Green Publishing

Seeing the broader system, context, and interconnections rather than focusing narrowly on individual components or immediate problems.

A cyclical process in which an action or change within a system influences future behaviour of that system. Reinforcing loops amplify changes, leading to exponential growth or decline, while balancing loops regulate change, maintaining stability or equilibrium. Feedback loops are fundamental to understanding system dynamics and predicting long-term outcomes.