24 Systems leadership for global sustainability

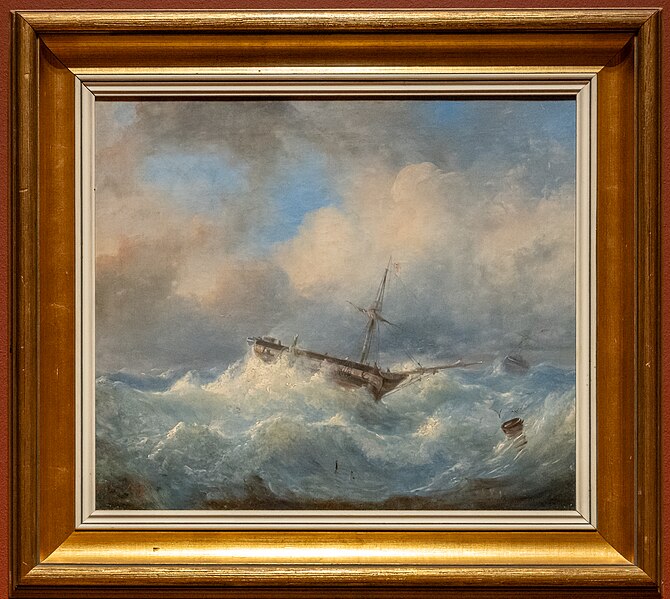

“Ship in Distress” by Raden Saleh (circa 1842). National Gallery Singapore. The image is dedicated to the public domain under CC0.

Navigating the Rising Tide Together: avoiding cabin thinking

Cabin thinking as metaphor

This metaphor encapsulates the challenge of global sustainability and similar ‘grand world problems.‘ Each nation, corporation, and community manages its own ‘cabin,’ making decisions that seem rational within their own limited scope. But climate change, economic inequality, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion affect the entire vessel. Unless we adopt a systems thinking and systems leadership approach, we will all decline together.

How systems thinking can help: Overcoming cabin thinking

Traditional leadership often focuses on managing individual parts, like maintaining a single cabin, without recognising how those parts interact within the larger system. Systems thinking provides a way to understand and intervene in interconnected problems before they escalate into catastrophe. Also, this approach recognises that problems such as poverty, climate change, and public health crises (as set out in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals) are not isolated issues but rather symptoms of deeper systemic structures. Consider how rising greenhouse gas emissions lead to global warming, which in turn accelerates ice melt and further destabilises the climate; a reinforcing loop that, like a ship crew ignoring water seeping in, becomes increasingly difficult and costly to address over time.

Donella Meadows’ (1999) work on leverage points suggests that rather than merely patching leaks, systemic change requires redesigning governance structures, shifting financial incentives, and rethinking consumption patterns. Just as viewing a ship as only its cabins ignores the hull that holds them together, addressing poverty or climate change in isolation fails to recognise their deep linkages to trade policies, energy use, and social justice. The climate crisis illustrates this perfectly: countries managing their ‘cabins’ individually may implement short-term economic policies that encourage fossil fuel dependence, tilting the ship further into instability and affecting everyone, rich and poor, developed and developing nations alike.

Systems Leadership for Global and Local Action

Traditional leadership models rely on centralised authority, but complex global challenges demand collaborative leadership at all levels. Like a ship’s crew working together in crisis, leadership must emerge from multiple actors, not just captains or high-ranking officials. This is more attuned to the Critical Systems Thinking paradigm, with its emphasis on stakeholder engagement. As the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) observe:

leaders, rather than providing a solution, “create opportunities for people to come together and generate their own answers” (Cooper and Nirenberg, 2012). Leaders should not only bring people together and encourage creative participation but should help people to embrace a relationship with uncertainty, chaos, and emergence.

The collective action problem

Instilling Urgency

Key Takeaways

-

Cabin Thinking Prevents Effective Systemic Action

The metaphor of a ship with isolated cabins illustrates the danger of fragmented decision-making in tackling global challenges like climate change, inequality, and resource depletion. When nations, businesses, and communities focus only on their own short-term interests, they fail to recognise how their actions contribute to system-wide risks, making coordinated solutions more difficult to achieve. -

Systems Leadership is Essential for Collective Action

Addressing grand challenges requires systems leadership, which emphasises seeing the bigger picture, fostering deep reflection, and mobilising diverse actors towards shared goals. Unlike traditional leadership, which relies on centralised authority, systems leadership thrives on collaboration across boundaries, ensuring long-term solutions that honour diverse perspectives, including Indigenous knowledge systems. -

The Collective Action Problem Must Be Overcome

Many actors hesitate to take responsibility unless others do, creating free-rider dynamics and reinforcing the tragedy of the commons. Systems leadership must align incentives, shift governance structures, and instill a sense of urgency to drive action. Without a shift from short-term economic and political priorities to sustainable long-term thinking, global crises will escalate, leaving no nation or organisation untouched.

References

- Cooper, J.F. and Nirenberg, J. (2014) Leadership Effectiveness. In Goethals, G. R., Sorenson, G. J., & Burns, J. M. (Eds) Encyclopedia of Leadership. (pp. 845-54). SAGE

Reference Online. Web. 30 Jan. 2012. https://study.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/reference6.4.pdf - IISD (2018). The essence of leadership for achieving the sustainable development goals. SDG Knowledge Hub. https://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/generation-2030/the-essence-of-leadership-for-achieving-the-sustainable-development-goals/

-

Meadows, D. H. (1999). Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. Sustainability Institute.

-

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing.

-

Olson, M. (1965). The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Harvard University Press.

-

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

-

Senge, P., Hamilton, H., & Kania, J. (2019). The Dawn of System Leadership. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2015, 27-33.

-

United Nations. (2015). Paris Agreement. United Nations Treaty Collection.

-

Yunkaporta, T. (2019). Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World. HarperOne.

The challenge of decision-making under uncertainty, where all possible states, outcomes, and probabilities are unknown or unknowable. It contrasts with Savage’s Small World, where decision-makers have well-defined probabilities and choices. The Grand World problem highlights the limits of rational decision theory in complex, real-world

A feedback loop within a system where an action produces a result that influences more of the same action, amplifying the effect over time. This process can lead to exponential growth or decline, depending on whether the feedback is positive or negative

A legally binding international treaty under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), adopted by 196 countries to limit global warming to well below 2°C, with efforts to keep it under 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. It emphasizes nationally determined contributions (NDCs), transparency, and financial support for developing nations. The agreement relies on voluntary cooperation and periodic progress reviews to drive global climate action.

A phenomenon in complex systems where larger patterns, structures, or behaviours arise from the interactions of smaller, simpler components without centralised control.

A collective action problem arises when individuals, organizations, or nations would benefit from working together to address a shared issue, but struggle to do so due to misaligned incentives, free-riding, or coordination challenges.

A situation where individuals, acting in their own self-interest, overuse and deplete a shared resource, leading to long-term collective harm. This occurs because the benefits of exploitation are private, while the costs are distributed among all users. Example: Overfishing in international waters, deforestation, and carbon emissions.

Free-rider dynamics occur when individuals or groups benefit from a collective good or effort without contributing to its creation or maintenance. This leads to an imbalance where some bear the costs while others exploit the system, potentially undermining cooperation and sustainability. Examples include tax evasion, vaccine hesitancy, and environmental inaction.