Robodebt: A Systems Intervention Analysis Using Meadows’ Leverage Points

The Robodebt scheme, an automated debt recovery program implemented by the Australian government from 2016 to 2020, serves as a powerful example of a failed systems intervention (Morton, 2024). It aimed to improve efficiency in welfare compliance by using automated data matching to identify and recover overpayments to Centrelink recipients. However, the program resulted in significant human and legal consequences, ultimately leading to a Royal Commission that deemed it unlawful and unjust.

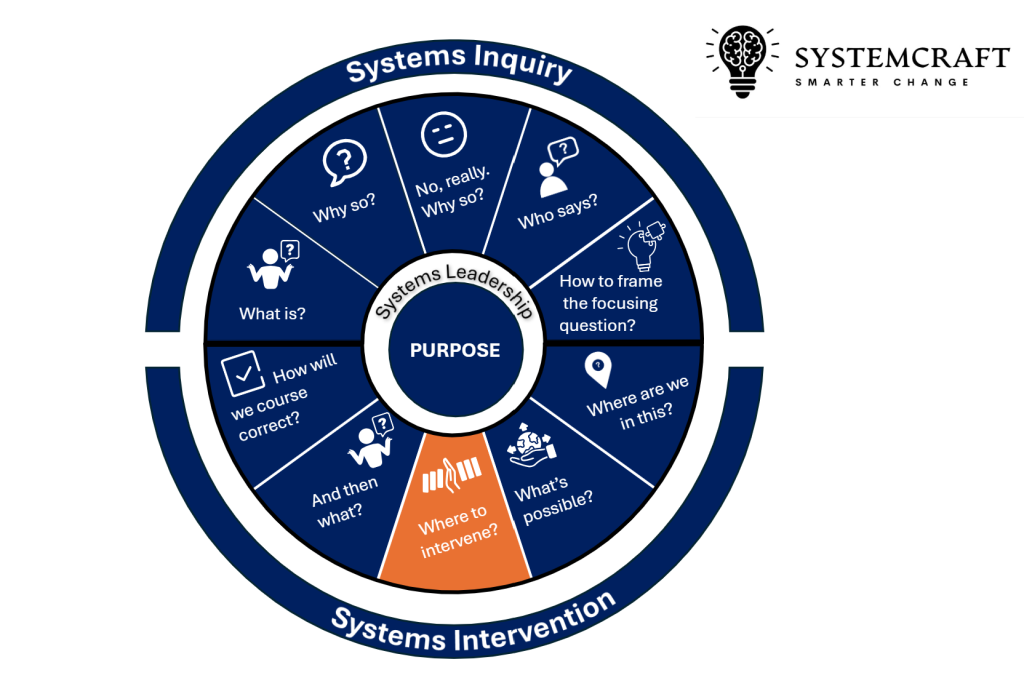

To analyse Robodebt as a system intervention, we apply Donella Meadows’ (2008) framework of leverage points, which identifies places to intervene in a system with increasing levels of systemic impact.

1. Constants, Parameters, and Numbers

(Least impactful leverage point)

Robodebt was framed as a simple efficiency improvement: automating the calculation of debts by averaging annual ATO income data to detect discrepancies in Centrelink payments. The parameters of the system—such as debt thresholds, repayment plans, and penalty structures—were adjusted to increase recovery rates. However, these numerical tweaks failed to address underlying problems, such as the system’s flawed logic of assuming stable income throughout the year, leading to false debts.

System Impact:

The focus on financial targets rather than accuracy led to wrongful debts being issued, damaging public trust.

2. Buffer Sizes and Reserves

The program reduced the buffer of human oversight, replacing caseworkers with an automated system that did not account for individual circumstances. Welfare recipients were required to provide evidence to contest debts, reversing the traditional burden of proof. This eroded a critical buffer that had previously allowed for case-by-case assessment, disproportionately harming vulnerable individuals.

System Impact:

The removal of human intervention accelerated errors and amplified harm, reducing the system’s capacity to self-correct.

3. Feedback Loops

The scheme disrupted the normal balancing feedback loops designed to correct errors in government administration. Traditional welfare debt systems relied on review mechanisms where recipients could contest calculations with the support of caseworkers. However, Robodebt weakened this corrective feedback by shifting to automated decision-making, requiring citizens to challenge debts through a bureaucratic process with a high burden of proof.

System Impact:

Negative feedback from affected citizens was slow to reach decision-makers, as individual complaints were dismissed as isolated cases rather than systemic failures.

4. Information Flows

Meadows highlights that who has access to information can be a major leverage point. In Robodebt, affected individuals received debt notices without transparent explanations of how the debt was calculated. Many did not realise that the debts were generated through income averaging rather than concrete evidence of overpayment.

Additionally, internal government warnings—such as legal advice questioning the scheme’s validity—were ignored or not escalated effectively.

System Impact:

Poor transparency meant that affected individuals and legal advocates struggled to challenge the scheme, while key government actors failed to act on early warnings of its flaws.

5. Rules of the System

A key structural change in Robodebt was the reversal of the burden of proof; where citizens had to disprove their debt rather than the government proving its validity. This rule change made it harder for individuals to contest debts and enabled the system to function without human oversight.

System Impact:

The rule shift fundamentally altered power dynamics, favouring automated decisions over human rights protections.

6. Self-Organisation (Ability to Adapt the System)

A resilient system allows for self-organisation, meaning it can evolve in response to problems. In Robodebt, rigid bureaucratic structures meant that once the system was in place, it became difficult to halt. There was institutional resistance to adapting, even when significant public criticism and legal challenges emerged.

System Impact:

Instead of adapting, the government doubled down on the scheme until legal action forced its termination.

7. Goals of the System

The stated goal of Robodebt was to improve debt recovery efficiency. However, the implicit goal was to increase revenue collection from vulnerable populations (Morton, 2024) rather than ensure the integrity of welfare payments. This focus on budget savings over fairness shaped system behaviours, leading to a disregard for ethical and legal considerations.

System Impact:

A goal misaligned with public interest meant that the system prioritised financial outcomes over citizen well-being.

8. Paradigms (Deepest Leverage Point)

The underlying paradigm driving Robodebt was the belief that welfare recipients are likely to be fraudulent and that automated enforcement is superior to human judgment. This neoliberal framing of welfare policy as a cost burden rather than a social safety net justified the aggressive approach.

System Impact:

The system reinforced harmful stereotypes about welfare recipients, leading to punitive policies that eroded trust in government services.

9. Transcending the Paradigm

(Most powerful leverage point, but rarely used)

A transformative shift would involve redefining welfare policy, not as a means of policing citizens but as a system designed to support social and economic participation. An alternative paradigm could prioritise citizen dignity, fair process, and human-centred governance, challenging the adversarial relationship between welfare administration and recipients.

System Impact:

Without shifting the paradigm, future interventions risk repeating similar failures under different guises.

Conclusion: Why Robodebt Failed as a Systems Intervention

By applying Meadows’ (2008) leverage points, we can see that Robodebt focused on low-impact system interventions (automation and efficiency metrics) while ignoring higher-leverage points like feedback loops, goals, and paradigms. The program ultimately collapsed because it disrupted balancing mechanisms, ignored ethical considerations, and was driven by a problematic view of welfare recipients (Holmes, 2023).

A more effective systems approach would have involved:

- Restoring feedback loops (allowing caseworkers and legal reviews to intervene).

- Ensuring information transparency (explaining debt calculations clearly).

- Aligning goals with fairness rather than revenue recovery.

- Challenging the punitive welfare paradigm.

This case illustrates the risks of solutionism (Morozov, 2013) in complex systems, where technological fixes are applied without understanding deeper systemic dynamics. It serves as a cautionary tale for future government automation projects, demonstrating that interventions must be designed with systemic insight, rather than a narrow focus on efficiency.