Module 3: Informed Decision Making

Topic 3.4: Decision Implementation

When the decision is being implemented, those responsible for the project execution should use a defined process that allows for regular decision and evaluation points, along with clear ‘green light-red light’ points, so that any project has both an effective business case rationale, and an effective development and launch structure.

Regular Decision Points

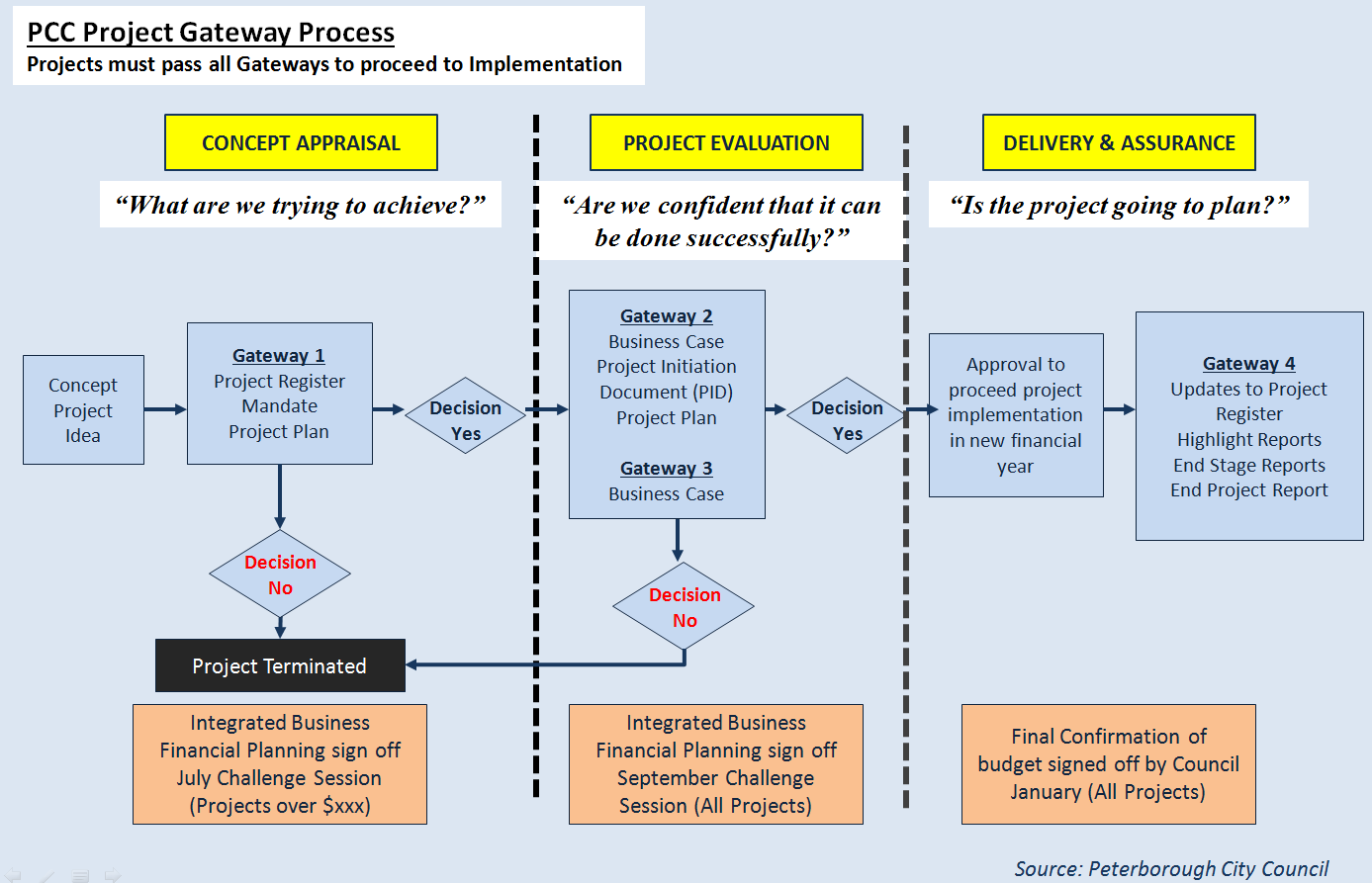

As the project is launched and continues systematic approach to ‘checking in’ is essential. One such tool from project development and management, and from project launch processes, is the ‘Stage Gate’ process that is widely used in industry. Here is an example of a stage gate process adapted for a public sector entity. See Figure 3.3: Peterborough City Council (PCC) Project Gateway Process. The PCC gateway process is based on the Office of Government Commerce (OGC) gateway process and is coordinated by the programme and project management team. Note the series of ‘stop-go’ decision points – hence ‘stage gate’.

Figure 3.3: Peterborough City Council (PCC) Project Gateway Process.[1]

As you follow the figure from left to right, you see specific stages and decision points, each with a ‘stop/go’ decision – thus the ‘state-gate’ notion. While it is possible that such processes can be used simply as ‘green light’ systems, when they are objectively applied, they can be very useful to keep initiatives on track and to keep key influences informed and involved.

The “Contestability” Lens

To many of you, the concept of contestability will be familiar. There has been significant sensitivity around this concept, and different jurisdictions differing views and levels of adoption, appetite for, and adoption of the concept. Regardless of the approach to, and acceptance of, the specific topic of ‘contestability’, the Australian Federal Government specifically states the following:

“The Contestability Framework (Framework) has been established to promote competition in the provision of Government functions and determine the most efficient way of designing and delivering government policies, programs and services.”[2]

Regardless of the mindset around alternate delivery models and providers, fundamental principles apply, as noted in the brief exerts from various jurisdiction provided at the beginning of this module. The questions then to ask should be whether or not the initiative, project or activity belongs within your agency, department etc.; whether it could or should be delivered by others; and is there a credible threat of competition? Your Porter’s Five forces analysis will be use here!

Finally, some universal principles apply when dealing with the public purse:

- Is there a system that will acknowledge and deal with failure? Risk?

- Are there alternative sources of supply?

- Will the initiative result in higher quality service outcomes: that is, does it deliver the specified public value, and it is the best mechanism to deliver that value?

- How does it relate to the core business of the agency/department?

- How does it contribute to the ongoing imperative of innovation within the agency/department?

As a final note, always refer back to your Public Value Scorecard and the business case model you have applied in as you develop your initiative or project.

Required

20 mins

Refer to the list of questions above. Use the list as a ‘check’ as you complete your Workplace Project.

- How is your proposed project ‘stacking up’?

- How does this influence your thinking?

- What might you do differently?

Recommended

30 mins

Biases that are potentially inherent in any organisation, and leaders need to develop a process to ‘check’ for these biases.

The following reading identifies a number of biases that might be operating when you and your department are trying to make decisions about a new initiative or business case.

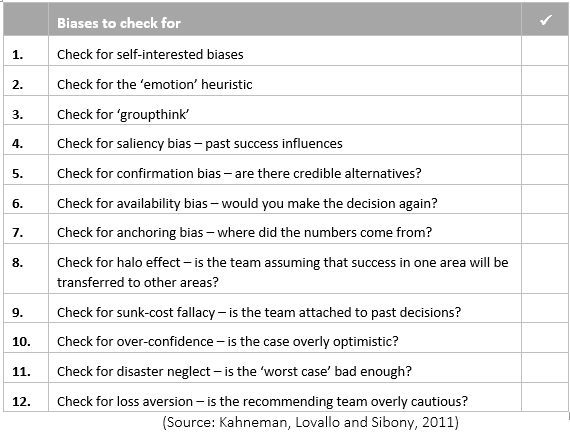

This reading poses 12 crucial actions that all decision makers should consider. Please check the details in the article. Here however is the short version of those actions. Use the Checklist for Biases presented in the following Table 3.3 when making a decision.

Table 3.3 Checklist for Biases[3]

With important decisions, leaders need to conduct a careful review not only of the content of recommendations but of the recommendation process. The 12-question checklist that has been devised by Kahneman, Lovallo and Sibony (2011) is intended to unearth and neutralise defects in teams’ thinking. These questions help leaders examine whether a team has explored alternatives appropriately, gathered all the right information, and used well-grounded numbers to support its case.

By using this tool, you can potentially build decision processes that reduce the effects of biases and upgrade the quality of decisions made in your teams. Leaders need to realise that the judgment of even highly experienced, competent managers can be fallible. A disciplined decision-making process, not individual genius, is the key to good strategy.

The ‘Contestability’ lenses

Contestability involves the process of creating legitimate competition for the delivery of government services. Increasingly public managers are being challenged to identify government services, which may benefit from undergoing a contestability process so as to assess potential for innovation and to enable service delivery for the right people and at the best price. Contestability is an attempt by government to compare and contrast the price and quality of government service provision with credible alternatives.

Most state public service sectors, except we understand for South Australia, are investigating how contestability might deliver better outcomes, and in some cases mandating explicit contestability tests. The most advanced in implementing contestability processes has been Queensland. In 2013, the Queensland Independent Commission of Audit identified contestability as the means to provide better value for money in the delivery of front-line services. The Queensland Government considers contestability to encourage more efficient and more innovative service delivery, whether by the public, private or the not for profit sector.

The Queensland Government Contestability Framework describes contestability as a process where government tests the market to ensure that it is providing the public with the best possible solution at the best possible price. It challenges the way services are delivered by looking for new and better ways to deliver the services Queenslanders want and need.

In an influential Australian report on contestability, Gary Sturgess (2012)[4] suggests that to inject greater competition and “contestability” into the supply side of the public service economy, these approaches are useful:

- Choice-based models that allow service users to select from a range of alternative providers, financed through government vouchers. Examples include choice-based lettings in public housing, personalised budgets in disability care and Medicare.

- Contestability, where service providers are benchmarked and institutions face actual competition, or a credible threat of competition. Contestability has been employed to good effect over the last decade or more, notably in reform of the NSW prison system.

(Sturgess, 2012, Page 5.)

Conclusion

In Module 3, we provided you with an overview of the complexities of data collection, analysis and enhancement, and we propose that you consider the overall umbrella of ‘big data’.

We proposed that

- you be well informed when you face decisions, and that you are abreast of the exponentially growing flood of data and tools to make sense of those data.

- The module also argued that that you have a firm understanding of your jurisdiction and agency’s overall set of processes to shape its decision-making processes, such as a financial framework.

- You now have an expanding set of tools and process that help you to investigate potential ‘business cases’ or opportunities, and to keep those that are launched, ‘on track’. These can be added to your Strategy Journey Map.

In the next module we help you to enhance your abilities to investigate your organisation’s operational processes and activities, which are informed by your estimation and communication of an initiative’s ‘value’, as it is relates to the organisation’s overall strategy and purpose.

- Jenner, S. (2010). Transforming government and public services: Realising benefits through project portfolio management. ↵

- Australian Government, Department of Finance, Contestability in the public sector ↵

- Kahneman, D.; Lovallo, D. and Sibony, O. (2011). Before you make that big decision Harvard Business Review, 89 (6), pp. 51-60. ↵

- Sturgess, G. (2012). Diversity and Contestability in the Public Service Economy. NSW, AUS: New South Wales Business Chamber. ↵