Unit Introduction

Welcome to PSMP Unit 3, GSZ633 – Managing Outwards in a Networked Government.

The focus of this unit is managing outwards within a complex system populated by multiple stakeholders affected by and affecting the way government does business.

The dynamic interplay between stakeholders, relationships, shared and competing interests, limited resources and emergent networks and technologies are shaping and reshaping government service delivery and community expectations of the role of government.

As the system of government operates in a contestable and contested environment, managers are challenged to demonstrate leadership and decision making to address key policy issues and to find creative ways to meet community needs.

Managing Outwards in a Networked Government explores the ways in which managers may embed systems thinking and stakeholder relationship management in ‘the way they do business’. Here is a brief overview of each of the modules:

- Module 1 – Responsive Government – focuses on the adaptive system of government, stakeholder impacts, how Artificial Intelligence (AI) is changing the workplace, the networked interplay between stakeholders (within and external to government), social media and the challenges of partnerships, networks and contract management.

- Module 2 – Cross Sector Collaboration – focuses on the challenges of stakeholder engagement, different levels of public participation, building social capital and a network management approach to managing the business of government.

- Module 3 – The Collaborative Imperative – focuses on strength-based strategies, including Appreciative Inquiry, to collaborate with stakeholders. Innovative whole of government approaches to managing service delivery are considered including integrated service delivery, place management, program linkages, case management and interdepartmental committees.

- Module 4 – Policy Communities – investigates the challenges of changing regulatory and investment environments and new policy skillsets. Market intervention and market regulation cases are explored. The module focuses on the system within which policy evolves, policy communities, participation processes, accountability regimes and benefits and limits of evidence informed policy.

- Module 5 – Contestable Government – focuses on strategic assessment of government services, big data, exploring community and markets to enable government service delivery. Solutions design embracing artificial intelligence and adaptive technologies are driving alternative service delivery models.

- Module 6 – Introduction to the Workplace Project – focuses on the expectations of the assessment in the final PSPM unit: GSZ634 Managing Operations for Outcomes, (workplace project proposal and report). This module will guide you in preparing a short draft project proposal by the end of GSZ633 Managing Outwards in a Networked Environment, for discussion with your workplace sponsor in preparation for GSZ634 Managing Operations for Outcomes.

To help you make the most of your learning and assessment in this unit, we strongly recommend that you keep a Reflective Journal. A reflective journal can be a valuable tool in developing greater self-awareness, capturing lessons and focusing your attention and behaviour on areas in which you want to develop. The form of your journal is less important than the process of journaling. You may want to use a notebook in which to write (and draw) notes. You may want to use an app such as ‘Day One’ (dayoneapp.com) or you may want to start a file on your computer or tablet.

Key Ideas and Concepts

Managing outwards in a networked government is about government’s relationship with the wider world, the environment and the community.

Social, economic, environmental and political dynamics influence the way government does business. The following key ideas and concepts are woven through the modules and will be at the core of your understanding of this unit:

- Systems thinking

- Stakeholders

- Network Management

- Language matters

- Social media

- Strength-based approaches

- Social capital

- Social licence to operate

Systems thinking

Systems thinking (as explored in GSZ631 Managing within the Context of Government) underpins our exploration of managing outwards in a networked government. The unit helps us explore Government agencies as active participants in a complex system of interests that are continually adapting and interacting. For example, some of the changes we have seen in the systems within which government operates include:

- Technological: speed of digital transformation, rise of networks and platforms, surveillance and cybercrime.

- Discontinuous change: workforce liberation (work from home), industry transformation through automation, science medical, agricultural breakthroughs.

- Challenge of ideology/ideas: Tribalism, polarisation, rising inequality; identity politics

- Globalisation: supra and super politics; loss of national autonomy, interrelationships and dependencies; supply chain complexities; financial flight.

Systems thinking has become a popular approach to tackle policy issues in the face of these trends. A systems thinker is willing to see a situation more fully, to recognise that issues and groups are all interrelated, to acknowledge that there can be many ways to bring about change and to champion change initiatives that may not be popular (Goodman, 1997)[1].

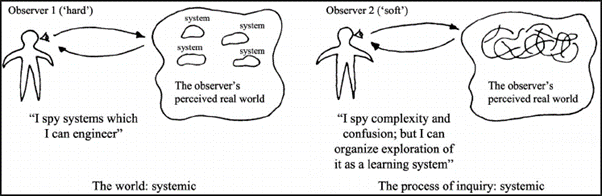

What distinguishes systems thinking is the way it approaches problem solving. Instead of an analytical point of view, it adopts holism. Peter Checkland (2010)[2] describes this as a difference between hard and soft systems thinking. The hard systems approach believes the world is understandable and solutions can be engineered. The soft systems approach is about using the process of inquiry to learn about the world; to see patterns and interrelationships and appreciate multiple realities as we attempt to understand or appreciate complexity. Checkland (2010), contrasts hard and soft systems thinking in the following way:

Systems thinkers have a strong appreciation of the importance of cultivating strong relationships for sustainable change, both within our work area and in the world external to your team, agency, department or division. As a systems thinker we build these relationships by listening actively, seeing the world through the eyes of others, being open to different ways of knowing and asking ‘where am I in this?’ (Social Change Agency, n.d.). Rather than engineering top-down change, as a hard systems perspective would lead us toward, the systems thinker experiments regularly, and adapts quickly from the feedback received. These principles and approaches will be explored and illustrated throughout the unit.

Wheatley (2006)[3] refers to a chaotic and unpredictable world where:

- small groups of engaged people alter the politics of the most powerful nations on earth

- very slight changes in the temperature of oceans cause violent weather that brings great hardship to people living far from those oceans

- pandemics kill tens of millions and viruses leap carelessly across national boundaries

- increased fragmentation has people retreat into positions and identities

- we have different interpretations of what’s going on even though we look at the same information

- there is constant surprise where we never know what we’ll hear when we turn on the news

- change is just the way it is.

Relational issues are everywhere as more studies emerge on partnership, followership, empowerment, teams, networks and the role of context. For managers and leaders, organisational life encompasses rational and non-rational elements of managing relationships, including:

- rational – systems, structures and processes

- non-rational – identity, relationships and information sharing

Our work in ‘Managing Outwards in a Networked Government’ is probably largely in the non-rational area i.e. acknowledging our context and interests, attempting to strengthen relationships to achieve outcomes and finding new ways to share information and build capability.

Stakeholders

Individual and groups interact throughout the system. Their relationships (alliances and conflict) make the system dynamic. Stakeholders may be defined as individuals or groups on whom the agency depends and without whom the agency would cease to exist.

Agency staff (and clients) are clearly stakeholders as are people in other agencies whether they be private, government or non-government agencies. Managing outwards in a networked government recognises stakeholders throughout the system of interaction within which the public manager exists.

Freeman (1984)[4] originally defined a stakeholder as ‘any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organisation’s objectives’.

The relative influence of stakeholders, and the scope of their involvement, changes as circumstances change. Stakeholder influence can be understood with reference to their sources of motivation, power, knowledge and legitimation. We will explore stakeholder influences in more detail in Module 1.

Network management

Managing outwards recognises the system(s) within which we work and the stakeholders with whom we interact. As managers, we have the challenge of co-ordinating multiple stakeholders to get work done. Coordination, collaboration, and even facilitation of diverse interests to achieve results may be informal or formal. We draw the idea of network management from technology where nodes and linkages exist in a system, or parties and relationships interact in a network.

Finding new shared information models for network management is a challenge for policy makers and managers. Formal horizontal governance arrangements and informal relational exchanges are creating new systems of purposive collaboration and value co-creation. Public managers are engaging more with networks for policy making and policy implementation, for example, in community health and catchment management.

Language matters

Think about the language we use in this unit: – stakeholders – citizens – customers – partners – lobbyists – competitors – offenders – consumers – refugees – pensioners… the terms we choose define the nature of the relationship between the parties within the system. They encourage us to pay attention to different aspects of our relationships and suggest that there are different purposes that they fulfil. They may also imply power differentials or judgments about the validity of stakeholder perceptions and concerns.

Social Media

Social media enables real time communication and connection between individuals and groups anywhere in the world. On the one hand, the symbiotic relationship between governments and media enterprises defines and challenges public debate. On the other hand, individuals can and do create media vehicles, for example GetUp!, to question power and to engage people in democracy or fighting for a cause.

Government schools have used crowdfunding (and peer-to-peer networks such as SpotCloud or Fiverr) to link individuals and groups with shared interests instantly (Friedrichsen & Muhl-Benninghaus, 2013)[5].

Paypal transformed its business from initially ‘beaming money between palm pilots’ to acquiring Ebay and then acting as ‘monetisation partner for small business’ creating novel payment solutions.

Lobbyists may use social media to gain attention and to attempt to influence decision-making. Media management protocols attempt to regulate relationships treading a fine line between freedom and surveillance. Social media is explored in more detail in Module 1 and the challenges of digital government in Module 3.

Strength-based approaches

Strength-based approaches reflect soft systems and relational approaches to change. The assumption is that people’s lives (and organisations) are socially constructed. There are multiple realities and we choose how we see the world around us i.e. as a problem or a mystery, glass half-empty or glass half-full. This is also a foundational element in soft systems thinking and distinguishes soft systems methodology from hard systems thinking.

More and more organisations are being influenced by the management application of Positive Psychology (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000)[6] which is the scientific study of what enhances life. It is all about building positive experiences, positive traits and positive organisations leading to increased quality of life for people. Positive psychology advances now include mapping human strengths, measuring wellbeing, the development of wisdom and the development of positive health. Becoming aware of strength-based approaches to management can significantly affect employee satisfaction and performance in a positive way as referred to in GSZ632 Managing Self and Others.

Appreciative Inquiry (Cooperrider & Whitney, 2005)[7] is a positive participant centred approach to change. Appreciative Inquiry offers ways to engage people in change based on respect, valuing diversity, authentic collaboration, shared purpose and shared benefits. Appreciative Inquiry focuses on ‘what works around here?’ rather than ‘what’s the problem?’ Module 3 explores Appreciative Inquiry theory and practice.

Social Capital

As agencies seek to collaborate with communities to identify needs and sustainable service systems, the process of appreciating and valuing and building on the capacity and capital within the

community is vital. Social capital can be understood in terms of social norms and networks. It manifests itself in civic participation where patterns of trust, reciprocity and co-operation contribute to economic development. Social capital differs from place to place. Lessons can be learnt from communities who actively self-manage.

Cox (1995)pointed to the importance of building social capital as much as other types of capital – financial, physical and human. Social capital is, according to this view:

Questions about social capital include the role of power and social conflict and social capital as a resource for local development and poverty eradication. Social capital is explored in more detail in module 2.

Social licence to operate

Managing outwards in a networked government implies distributed power between and across all elements of the system. At times government may regulate activities, set standards and issue licences however; government agencies are also subject to approval processes by the electorate, communities and local groups.

Social licence implications for public sector management are explored in more detail in Module 2.

As you proceed through the materials in this unit, think about the dynamic system within which you work: who are the key stakeholders, what are the major debates, which are your most important relationships and how may your role be changing over the next 12 months.

15 min

Deeper Learning

- Goodman, M. (1997). Systems thinking: What, why, when, where, and how. The Systems Thinker, 8(2), 6-7. ↵

- Checkland, P. & Poulter, J. (2010). Soft Systems Methodology. In M. Reynolds & S. Holwell (Eds.), Systems Approaches to Managing Change: A Practical Guide (pp. 191-242). London: Springer London. ↵

- Wheatley, M. J. (2006). Leadership and the new science : discovering order in a chaotic world (3rd ed.). Berrett-Koehler. ↵

- Freeman, R. E. (1984) Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman Publishing ↵

- Friedrichsen, M., & Muhl-Benninghaus, W. (2013). Handbook of social media management: Value chain and business models in changing media markets. Berlin: Springer ↵

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14. ↵

- Cooperrider, D. L. & Whitney, D. K. (2005). Appreciative inquiry: A positive revolution in change. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler. ↵

- Cox, E. (1995) A truly civil society: Broadening the views. The 1995 Boyer Lectures. Retrieved from http://www.mapl.com.au/pdf/Eva%20Cox.pdf ↵