TOPIC 4.4: Defining a policy ‘problem’

Because of the diversity of people and organisations involved in the policy process and its competitive and political nature, there are likely to be many different perspectives on the nature or causes of a policy problem.

Thus, problems come to the attention of government in a variety of ways. Some mechanisms through which problems may be identified:

Systemic indicators |

Statistics, data and other means used by government to monitor problems and issues. Big increases in unemployment or lengthening delays for elective surgery in public hospitals are likely to attract media interest, focusing on lack of employment opportunities or insufficient funding for public hospitals. Policy-makers and policy advocates will be quite selective in their use of systemic indicators to support their particular conception of a problem. You can probably think of examples from your own experience where different individuals or groups have offered different interpretations of a particular set of data or indicators. |

Focusing events, crises and disasters |

Incidents such as the occurrence of a crisis or a disaster can be the impetus for government to take action. An example would be the establishment of a Senate inquiry into mental health services prompted by the discovery that a mentally ill woman had been wrongly incarcerated in an immigration detention centre. |

Symbols |

Sometimes an evocative image or phrase attracts attention to a particular problem or issue. An example was the campaign by animal protection activists to prohibit the hunting of baby fur seals. A photograph of a beautiful seal against a background of blood-soaked ice built momentum and public support for the campaign. |

Personal experience |

The ways in which policy-makers perceive and interpret problems and issues is conditioned by their personal and professional experience, which plays a crucial role in the identification and prioritisation of policy issues. An example of this would be the efforts by Marshall Perron, former Chief Minister of the Northern Territory, to introduce voluntary euthanasia legislation in that jurisdiction. His mother and a friend had each died painful death after long battles with terminal illness. |

Feedback |

In the normal course of events, policy-makers receive all sorts of feedback about developments in their policy subsystem: performance monitoring, research, casework, correspondence and so on. This may be formal (official reports, inquiries, intergovernmental communication) or informal (media reports, representations, meetings, other kinds of contacts that occur among members of a policy community). |

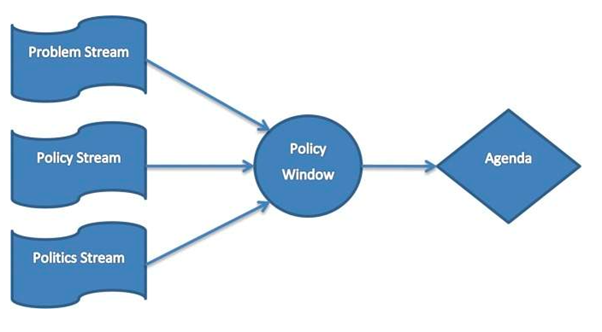

John Kingdon (2003)[1] in his classic Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies argues that problems come to the government’s attention when a ‘policy window’ opens: when politicians are willing to vote for an idea, when the ‘problem’ or issue is a priority for enough people, and there exists a viable solution or ‘policy.’ The model below depicts this process:

Kingdon (2003) maintains that there must be ‘policy entrepreneurs’ ready to take advantage of this policy window opening up, because they can close quickly when any of these three streams change. People who want to see change must be ready to activate their sources of power and ensure that a policy decision is made. Policy entrepreneurs are not always politicians: Eddie Mabo for example prepared the way for indigenous land rights legislation and could be considered a policy entrepreneur.

20 mins

If the three streams (problem, policy, politics) don’t come together to create the policy window (or opportunity for action), policy entrepreneurs know it is not the right time to push forward on legislation. For many years in Australia, it never seemed to be the ‘right time’ to change marriage legislation to allow same-sex couples to marry. You can find a history of this policy issue here.

- What do you think caused the policy window to open for the issue of same-sex marriage around 2015?

- Why were politicians inclined to put it on the policy agenda then, when they were reluctant before for many years?

- Who were the policy entrepreneurs in this history?

Recommended

25 mins

- Kingdon, J. W. (2003). Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. New York : Longman, 2003 ↵