TOPIC 1.7: Partnering

Cross sector relationships are emerging in many forms. The Practical Guide for Partnerships 2021 outlines some of these emergent relationships.

Recommended Reading

15 mins

It may be useful to frame the concept of contracting within the context of the many forms and motives associated with relationships more generally. Knowing the type of contractual relationship you are seeking or with which you are involved, makes it easier to determine the nature of legal and financial mechanisms, reporting requirements, operational requirements, boundaries and other related strictures that you will need to be aware of or involved in to ensure the contract meets the desired objectives. The following table (Table 1.4) differentiates between the different motivations underpinning various partnership formations.

| Motive | Comment |

| Management reform and modernisation | By working in partnership with the private sector, public managers will learn how to run programmes more flexibly and efficiently |

| Attracting private finance | By partnering, public agencies will be able to tap into private finance, enabling them to pursue projects which could not (yet) be afforded from public budgets alone |

| Public legitimacy | Participation in a partnership is seen as a good in itself – symbolic of a pooling of talents from government, the market sector and the voluntary sector in the pursuit of worthy public purposes |

| Risk shifting | Private partners assume part or the whole of the financial risk associated with projects. Similar to attracting private finance motive |

| Downsizing the public sector | Like contracting out and privatisation, public-private partnerships may be seen by those who favour downsizing the public service as a way to get tasks which were formerly performed by public sector staff handed over to the staff of commercial or voluntary organisations |

| Power sharing | Partnerships may be seen as promoting more cooperative, ‘horizontal’ less authoritarian and hierarchical relationships |

Table 1.4: reasons for forming relationships.

‘Contracting-in’ refers to a situation where a public sector entity enters into commercial contracts to provide services to users in either the public or private sectors. Such contracting raises questions about why government would be involved in a business activity where the market is functioning effectively. Governments generally restrict their involvement in commercial areas to:

- providing policy advice,

- coordinating activities at all levels of government,

- monitoring and regulating,

- providing specialised services that the private sector is not equipped to offer, such as for defence purposes,

- fostering emerging markets but withdrawing from them as the private sector develops the necessary skills to take over,

- facilitating the private sector’s work through activities such as technology transfer, joint ventures and export enhancement.

Market based solutions and alternatives for service delivery include transferring ownership, sharing risks, outsourced provision, partnerships, private or community based providers and management contracts.

In recognition of economic concerns, the Commonwealth Government and some State Governments have developed extensive programs of asset sales, with government business enterprises (GBEs) such as Medibank, Australia Post, the Commonwealth Bank and Telstra being either wholly or partially sold into private ownership. To deal with other business units, some governments have established a policy that commercialised entities should not compete for private sector work, except where the entity is an expert provider (such as the CSIRO, which often contracts to do research on behalf of private companies, or the Australian Bureau of Statistics).

The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) is an example of government creating a new relationship with private and community providers of disability services and consumers (people with disabilities, their carers and families) of the services.

There are key distinctions between commissioning, strategic procurement and contestability processes. Commissioning may involve creating and building markets to deliver government services. Strategic Procurement may involve collaborating with suppliers and vendors to develop long term partnering arrangements. Contestability involves the process of creating legitimate competition for the delivery of government services. Increasingly public managers are being challenged to identify government services, which may benefit from undergoing a contestability process to assess potential for innovation and to enable service delivery for the right people and at the best price. We will explore contestability processes more in Module 5.

In the meantime, check out the formal Australian Government Contract Management Guide (link provided in Activity box below). Managing outwards in a networked government is likely to draw on your ability to develop and manage contracts with stakeholders in your service system.

The gist of Module 1 is that different approaches to collaboration are evolving as governments (and others involved in governance) seek new ways to gain access to resources, expertise and market driven management as a way to solve the emerging problems that public managers face.

Relationships between organisations are being transformed as cross sector collaboration increases in response to complex global and local challenges. The following guide to cross sector collaboration outlines a range of approaches to partnership work and practice.

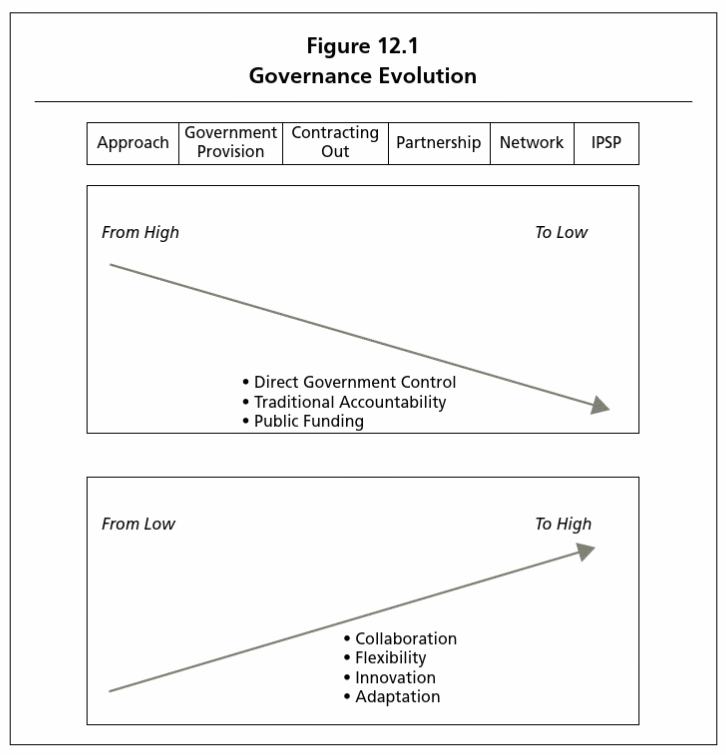

The challenges of governance today are substantial enough when governments operate within the framework of the traditional bureaucratic model, let alone when they move to more collaborative arrangements that anticipate less direct government control. Figure 12.1 shows how different approaches to collaboration have evolved over time as governments (and others involved in governance) seek new ways to gain access to resources, expertise, and market-driven management as a way to solve the emerging complex problems that public managers face.

As public managers have moved from the traditional provision of services, to contracting out, to partnerships, networks, and now IPSPs, each form of collaboration is seen as having some additional benefits to public service delivery. At the same time, these engagements mean an incremental loss of direct control by government and greater discretion and autonomy on the part of the collaborators. The IPSP is the extreme case— near autonomy from government, but with the greatest potential for responsiveness, flexibility, and innovation.

The evolution of these alternative approaches produces interesting choices for public managers: promising for their potential and threatening for what they take away. The paradox for public managers is that in order to gain full access to the benefits of these new approaches— collaboration, flexibility, innovation, and adaptation— public managers must relinquish the very essence of the conventional idea of what it has come to mean to act as government managers: formal control over the production and delivery of public services. Even public managers who endorse CSC are reluctant to step back from the view that government’s prerogative should prevail in all such arrangements— even under the most extreme circumstances, where government is contributing minimal or no resources at all.[1]

45 min

Forrer, J. J., Edwin, J., & Boyer, E. (2014). Network Governance. San Francisco CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Reading: Chapter 4 (pp. 85-86 only)

- Reading: Chapter 12 (p. 301 only)

Read the guide below and consider the following questions:

- Do you carry out risk management in relation to all contracts?

- Do you liaise with your legal area?

Recommended

20 min

Read the following for examples of citizen juries at work.

- What issues do you think warrant a citizen jury process?

- What are the risks and benefits of citizen juries?

- Forrer, J. J., Edwin, J., & Boyer, E. (2014). Network Governance (pp. 301-302). San Francisco CA: Jossey-Bass. ↵