Module Six: Innovative Government and Reform

TOPIC 6.4: How does Australia achieve a responsive public sector?

Mechanisms of responsiveness

Governments of all persuasions are eager to have a bureaucracy, which is responsive both to its policy agenda and to the community. In this section, we are concerned about the latter: bureaucracy (government) being responsive to the community.

Regardless of the size, there is still a demand by the government of the day to have a responsive public sector.

In Australia, the Rudd Government (Advisory Group on Reform of Australian Government Administration, 2010, p ix)[1] set out 9 principles for reform in a ‘Blueprint’, the first of is ‘delivering better services for citizens’, including simplification, improved service delivery through more use of the community and private sectors, closer partnering between the levels of government. The second is ‘creating more open government’; including better access to online government services as well as service co-design with the community.

Although the Rudd Blueprint is 14 years old and 6 Commonwealth governments ago, the fundamental principles expressed are still as relevant today as when they were first published. Many of the Thodey Review recommendations and the wider APS reform agenda discussed in Topics 6.2 and 6.3 align with these principles.

At the state and territory level over this period, each of the public services have also been undergoing renewal based on these same broad principles. Across Australia, we have seen these values espoused, but how the administrative response to them is orchestrated may be different. NDIS is an example where the Commonwealth Government is exploring new funding arrangements to improve service delivery.

‘Decentralisation’ has been seen as a geographic issue for all levels of government. For example, the NSW government pushing service hubs outside the CBD or the WA government setting a policy objective to ‘Ensure the general standard of government services and access to services is comparable to the metropolitan area’ (Western Australia Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, 2023, p. 3).[2]

As important and beneficial as these initiatives are to bring services closer to users, achieving a genuine redistribution and sharing of power between government and its citizens requires a deeper change. Improving ‘openness’ in government will not be centred upon recruitment and provision of services to target groups alone. What is also needed is ensuring depth of involvement in the business of government by a wider raft of groups and citizens to form a partnership in the outcome.

The following section provides some other types of initiatives beyond simple decentralisation of service delivery. When reviewing these initiatives consider if your agency or jurisdiction already uses or is considering using them.

- How well were they received if already used and did they improve either engagement or outcomes?

- If they have not been used – why do you think that is so?

Other initiatives available to government

e-Government – Increasing government capability to offer services electronically and remotely.

Citizen boards – A range of citizen boards are possible:

- Governance Board: Oversighting public community facilities (e.g. Hospital Boards)

- Review Board: Reviewing public sector investigations (e.g. Police abuse review)

- Advisory Board: Volunteers from the community providing advice and support to government agencies (e.g. Integrated Catchment)

Citizen charter – Citizens’ Charter is a document, which represents a systematic effort to focus on the commitment of the organisation towards its citizens in respect of standard of services, information, choice and consultation, non-discrimination and accessibility, grievance redress, courtesy and value for money. This also includes expectations of the organisation from the citizen for fulfilling the commitment of the organisation. You may wish to review the Indian Government’s Citizens’ Charter.

Consultation – A range of processes, which get community perceptions and needs prior to introducing policy or programs.

User pays – Services are offered but user pays for the provision reducing the impost across the community or for persons who do not partake.

Pay for results – To reward service providers based on achievement in order to reduce waste. (E.g. pay universities when student successfully graduates or gains employment not merely on enrolment which encourages large classes and minimal services, leading to high drop-out).

Privatisation – Government going into business: to reduce impost on the public sector (E.g. Utilities, Commonwealth bank, Telstra)

Corporatisation – Government operating an agency as if it is a business (E.g. Australia Post).

Outsourcing – contracting government services to Non-Government Organisations.

Citizen Scorecards – Citizen Report Cards[3] are participatory surveys that provide quantitative feedback on user perceptions on the quality, adequacy and efficiency of public services. They go beyond just being a data collection exercise to being an instrument to exact public accountability through the extensive media coverage and civil society advocacy that accompanies the process.

Participatory Budgeting -Directly involves local people in making decisions on the spending and priorities for a defined public budget.

Private-Public Partnerships – Using private capital and/or expertise to build public infrastructure such as roads, bridges, trains, tunnels.

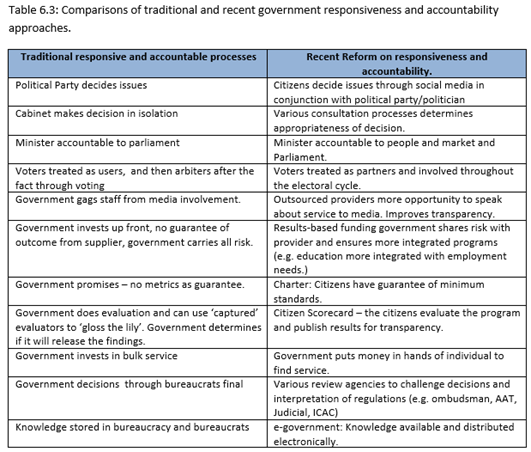

Comparisons of responsive and responsible government

As this is the final module, the following table (Table6.3) may assist in reviewing the earlier modules and comparing the traditional notions of responsive and accountable government with the emergent model.

Recommended

70 mins

Hart, P. ’t. (2023). Working with uncertainty and discomfort: Paul ‘t Hart on the role of the post-COVID public servant. ANZSOG.

Citizen focussed public service is attracting considerable international attention and the following reading by Podger et al (2012) explores the international applications of it, especially as it relates to China and compares that to what is happening in Australia. In China, where the absence of formal democratic processes persists, the idea of a social accountability – through emerging NGOs, and more rigorous media – is interesting and assists in understanding how responsiveness and accountability interact (Downwards, upwards and horizontal).

- Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. (2010). Ahead of the game : blueprint for the reform of Australian Government administration / Advisory Group on Reform of Australian Government Administration. Australian Government. https://www.apsreview.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/Ahead%20of%20the%20Game%20-%20Blueprint%20for%20the%20Reform%20of%20Australian%20Government.pdf ↵

- Western Australia Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, (2023). WA Regional Development Framework October 2023. https://www.wa.gov.au/system/files/2023-11/wa-regional-development-framework-october-2023_0.pdf ↵

- Waglé, S., Singh, J., & Shah, P. (2004). Citizen Report Card Surveys : A Note on the Concept and Methodology (Vol. 91). World Bank, Washington, DC. ↵