Module Six: Innovative Government and Reform

TOPIC 6.2: What is the future position of the public sector in the community?

Overview

You now have canvassed ideas about the type of reform that is occurring in countries with both a European and Asian perspective and pragmatic approaches have been chosen to assist you to think about your own workplace. In Australia, there have been reforms based around the NPM approach and we asked you to think about public sector paradigms in Module 2 and again now in Module 6, Topic 2 assists you to think about the reform landscape and be aware of some of the limits and benefits.

In previous modules, we have made the case that there is a relationship between the ideology and the size of government. Neo-liberal thinking has evolved government as being, at best, a necessary evil and, at worst, merely a sop to legitimise capitalist endeavour in the eyes of the community.

NPM strategy in this frame is a drive towards an outcome of minimal ‘government’: governance rather than government; or “steering rather than rowing” (Osborne & Gabler 1992)[1]; and largely, to do this through contracting others to deliver “The contract state”. If everything presently managed by government can be done by the private sector, contracted by the state, then the logical next step is for Parliament to get a private sector organisation (a consulting company ,say) to run the contracting and do without a bureaucracy.

DeVries & Nemac (2013)[2] believe the GFC and the financial reverberations, as a consequence of poor regulation and trans-global connectivity of the financial system displacing risk, have shown the limits of that neo-liberal notion:

“The dramatic decline in GDP, public revenues and stabilization expenditures reveal the urgent problems that many countries face. It is in those circumstances that industry, banks but also common people turn to their governments and demand solutions, which cannot be provided for by the market nor by a minimalistic public sector. It is not sufficient just to increase taxes and to implement cross-sectoral general cuts. In such a severe situation it becomes obvious that the one-size-fits-all solution of minimizing the influence of government has serious drawbacks and that the ideology behind NPM has reached its limits.”

Public value

As we examined in Module 2, Public Value has become the current paradigm in use in most Australian jurisdictions.

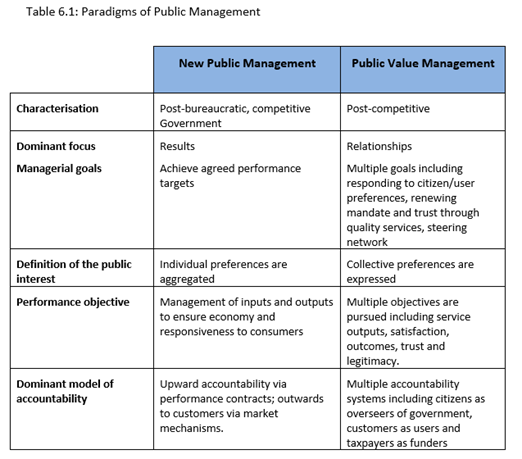

O’Flynn (2007)[3] argues that the new paradigm is Public Value and usefully compares them in Table 6.1: Paradigms of Public Management.

The Modern Public Service

As has been noted throughout this unit, the modern public service has multiple challenges to which it will need to adapt.

Some community issues are of such a scale that governments are overwhelmed in their efforts to deal with them. For example, mental health concerns, affecting nearly fifty percent of the population in a significant mental health incident at one stage in their life, are so personal and pervasive, that the traditional medical model has failed to cope. (See Mendoza et al: 2013)[4].

A case-managed and networked approach, involving the community and the resourcing of soft systems, rather than following the bureaucrats’ traditional urge to construct a bricks and mortar response is what a number of commentators believe is required.

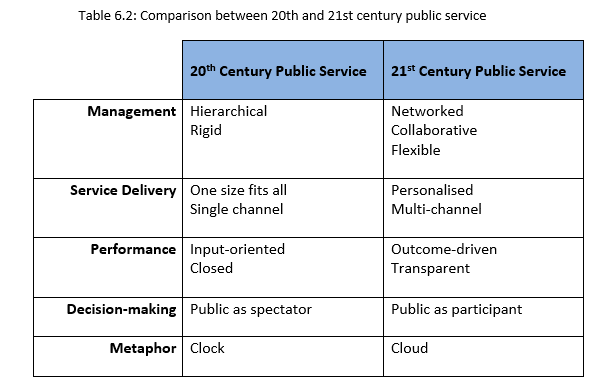

These issues are merely indicative of the drivers, which may require a different public service in this century. The Victorian government drew the following scenario in its efforts to inform the community of the type of service, which may be required in the 21st Century. (See Table 6.2)

Independent Review of the Australian Public Service (Thodey Review)

Background

In May 2018, the Turnbull Government commissioned a review of the Australian Public Service (APS), which was led by an independent panel chaired by Mr. David Thodey and published at the end of 2019. It is one of the more substantive reviews of the APS conducted since the Coombs Royal Commission of 1976 which largely shaped the structure, approach, and operations of the APS for decades. The aim of the Thodey Review was to examine the leading domestic and international public and private sector practices. It sought to ensure the APS is fit-for-purpose for the coming decades, by identifying areas where transformational reforms could be implemented.

Overview of Recommendations

The Thodey Report into the APS was released in 2019 with some 40 recommendations for change. The background and details of the review are dealt with below. The report is available at www.apsreview.gov.au[5]

The review concluded that the APS was not broken, but it was not performing at its best, and it was not ready for the big changes and challenges that Australia would face between then and 2030. The review thus proposed a set of guiding factors and specific recommendations to achieve a successful transformation of the APS. These were summarised in the report in Figure 1.

The Morrison Government’s response

As a response to the Thodey Review, the federal government released in late 2019 an APS reform agenda titled: A World-Class Australian Public Service an in the 2021 the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee reviewed both the Thodey Report and the Government’s own reform agenda report. The Senate committee report was titled APS Inc: undermining public sector capability and performance: The current capability of the Australian Public Service.

The Senate committee agreed with the observation made in the Thodey Review that although the APS is not broken, it is also not performing at its best. It did however form the view that there ‘is a clear and urgent need for transformation within the APS in order to halt capability erosion and restore institutional memory so that, as an institution, the APS is better equipped to serve the Australian public’ (Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee, p. 15).[6] The Senate Committee reviewed the 40 specific recommendations presented in the Thodey Review and agreed with 15 fully, agreed in part with another 20, noted 2 and did not agree with 3 of recommendations.

The Albanese Government’s APS Reform Agenda

Background

In 2022 the newly elected Albanese Labor government had as one of its priorities to review the functioning of the APS. A number of high-profile issues such as ‘Robodebt’ which developed under the previous Coalition governments were perceived to have affected the credibility and competence of some parts of the APS. In October 2022 Senator the Hon Katy Gallagher, Minister for the Public Service announced a new APS Reform Agenda that would ‘build on the Thodey Review’ and that the `reforms are about putting the people who use our services at the centre, about rebuilding what’s been allowed to erode, and about valuing and reinvesting in the APS’s most valuable resource – its people’ (Gallagher 2022).[7]

The APS Reform Agenda

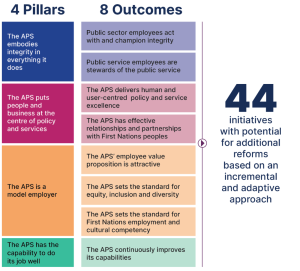

The reform agenda has four priority areas (pillars) for an APS that:[8]

- embodies integrity in everything it does.

- puts people and business at the centre of policy and services.

- is a model employer.

- has the capability to do its job well

These priorities are to be achieved across 8 outcome areas through the delivery of 44 initiatives.

Current status of the reform agenda

The amending legislation underpinning the reforms (the Public Service Amendment Bill 2023)[9] passed the House of Representatives in August 2023 and in early March 2024 was before the Senate awaiting passage.

The Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee recommended that the Senate pass the Bill. Among its various findings the Committee noted the recent findings of the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme and the role of many lower-level, not senior level, public servants, in first raising concerns about the Scheme underscoring the importance that ‘every public servant should be required to uphold a value of stewardship that requires them to understand the long-term impacts of what they do’ (Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee, 2023, p. 29).[10]

In November 2023 the government released the Charter of Partnerships and Engagement which sets out principles for improving the way the APS puts people and business at the centre of policy, implementation and delivery (PM&C, 2023).[11]

Recommended

New Public Management and Beyond (30 mins)

New Public Management to Public Value (15 mins)

Critics of public value from the school of ‘distrust the bureaucracy’ see this as a move by the public sector to dilute the performance criteria and appeal to the argument that the ‘public service is too broad/complex to measure’, in an attempt to avoid accountability. However, given the mega-trends and the argument for complexity, the public value model has some attractive features, as O’Flynn (2007) outlines in the following reading.

Public Service Reform (45 min)

Reflections

- What changes have you noticed in the way the public service operates since you joined?

- Is there a more competitive culture than previously, with contestability a watchword, or more collaborative, as government attempts to ‘join up’?

- What have you noticed about your career path? Is there more opportunity, less, different?

- Is the public sector more ‘political’ as a consequence of attempts to make it more responsive?

Deeper Learning

30 mins

Gallagher, K. (2022). An Ambitious and Enduring APS Reform Plan. IPAA ACT.

- Osborne, T. & Gaebler, D. (1992). Reinventing Government. New York:Addison-Wesley. ↵

- DeVries & Nemac. (2013). Public Sector reform: an overview of recent literature and research on NPM and alternative paths. International Journal of Public Sector Management. Vol. 26 Iss 1 pp. 4 – 16 ↵

- O’Flynn, J. (2007). From New Public Management to Public Value: Paradigmatic Change and Managerial Implications. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 66(3), 353–366. ↵

- Mendoza, J., Bresnan A., Rosenberg, S., Elson, A., Gilbert, Y., Long, P., Wilson, K., & Hopkins J. (2013). Obsessive Hope Disorder: Reflections on 30 years of mental health reform in Australia and Visions for the future. Technical Report. ConNetica, Caloundra, Qld. ↵

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2019). Our Public Service, Our Future: Independent Review of the Australian Public Service. Australian Government. https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/independent-review-aps.pdf ↵

- Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee. (2021, November 25). APS Inc: undermining public sector capability and performance: The current capability of the Australian Public Service. Parliament of Australia. ↵

- Gallagher, K. (2022) Albanese Government’s APS Reform agenda. Speech to the Institute of Public Administration Australia. 13 October 2022. Canberra on Ngunnawal Country. ↵

- APS Reform. (2023). Australian Public Sector Reform: Annual Progress Report 2023. Australian Government. ↵

- Public Service Amendment Bill 2023 (Cth). https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22legislation%2Fbills%2Fr7044_first-reps%2F0000%22;rec=0 ↵

- Senate Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee (2023). Report on the Public Service Amendment Bill 2023 [Provisions]. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Finance_and_Public_Administration/PSABill2023/Report ↵

- APS Reform. (2023, November 21). The Charter of Partnerships and Engagement. Australian Government. https://www.apsreform.gov.au/news/charter-partnerships-and-engagement ↵