Module Five: System Thinking

TOPIC 5.4: What are Soft Systems Tools?

Soft systems methodologies for exploring different perspectives

To this point, we have argued that there are issues facing government which might be described as ‘messes’ or ‘wicked problems’, and that systems thinking may be in a better position to deal with these than the traditional modes of problem solving.

But how does one go about doing ‘systems thinking’? There are various methodologies and tools utilised depending on the category of system and problem. Aspects of one approach, Soft Systems Methodology (SSM), will be introduced in this Unit.

One of the many issues a public sector manager has to deal with is the inconvenience of having to deal with a world, which has infinite variety and various shades of grey. Many of the issues government faces are ‘social issues’ comprised of individual actors each capable of acting independently and creating perturbations in the political system if they so decide. What tools are available to those working in social policy as distinct to working on physical projects?

Peter Checkland, one of the leading developers of SSM, talks about ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ systems. Hard systems are defined by clearly formed processes and structures, which can be clearly quantified and soft systems, which are ill defined, fuzzy and can be difficult to quantify. The definition of hard systems often applies to man-made and physical systems, whereas soft systems largely concern human and social activities. See Checkland & Scholes, (1990)[1] and Checkland & Poulter, (2020)[2] for a deeper understanding of SSM.

Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) attempts to deal with the divergent views of the various stakeholders about the definition of the problem within the system (Zokaei, K., et al., 2010)[3].

A criticism may be that it is largely positivist (i.e. describes what is) and may not have transformative power (i.e. to change anything) unless it is coupled with other interventions in the systems’ thinker’s toolkit.

Defining the boundaries of soft systems

Prior to launching into a discussion of SSM, it is also appropriate to comment upon ‘boundaries’. First, a system is a bounded reality: It has borders to assist with recognition. Churchman (1981 in Mason & Mitroff)[4] suggests that our choice of what lies within a system is essentially an ethical decision. As Hummelbrunner (2011)[5] notes:

“…what lies inside a system, you implicitly or even explicitly marginalise what lies outside the system … your choice of what lies within a system’s boundaries depends on your perspective or more deeply your values.”(p.303-4)

Second, even though we talk about ‘holism’ it is physically and intellectually impossible to take everything into consideration. We have to draw a boundary somewhere and we have to be critically aware of why and where we draw that boundary. As Hummelbrunner (2011: 304) explains:

“There are two reasons for being self-aware and critical of boundary decisions, one pragmatic and one ethical. The pragmatic reason is that unless we understand and address the consequences of boundary decisions, we will never fully understand the consequences of our own intervention in a particular situation nor can we anticipate the responses of others to that intervention. The ethical reason is that without that critical assessment of the boundaries we (and others) draw around a situation, we may inadvertently increase social and environmental inequities.”

As a consequence, of boundary decisions, you may include a certain group of stakeholders for consideration and not another, yet successful outcomes may require that absent group to be involved. Consider Corrective Services placing a boundary around their feeder system limited to the judicial system (the Courts), the Police may be left out of stakeholder considerations. If Police are included then mental health might be left out. The list could possibly include training systems to reduce recidivism, and employers to provide meaningful occupations and expand wider. For practical (pragmatic) purposes considerations might need to be limited to the justice system, but ethically, society may be left with people best processed into a mental health system being incarcerated for convenience in the prison system.

Exploring Soft Systems through rich pictures

Equipped with this background it is now time to consider using the tool in the form of developing a ‘Rich Picture’ from a case study on the Kimberley Gas Project. When you have completed the exercise, make sure you bring it with you to the face-to-face workshop.

Soft systems methodology (SSM) has been widely used across many contexts, including in complex project management in the defence industries. Checkland (1990, 2020), intended the methodology to deal with the subjective aspects of problem situations while maintaining adequate standards of rigour.

It is described here in the context of complex projects where practitioners need to explore real world problems in complex ‘messy’ situations. The ‘researcher/practitioner’ refers to an internal person with SSM skills engaged to lead or work with a project team (or he or she could be a consultant).

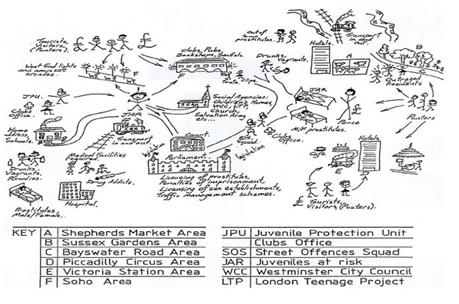

In this step, the researcher/practitioner develops a detailed description, a “rich picture”, of the situation within which the problem occurs. This is most often done diagrammatically.

The rich picture should aim to capture important linkages, and the culture and climate of the problem-situation. According to Checkland (1990, 2020), it tries to capture the relationships, the value judgments people make, and the “feel” of the situation.

Rich pictures represent a particular situation or issue from the viewpoint(s) of the person or people who drew them. They can show relationships, connections, influences, perceived cause and effect, and political aspects of the situation.

They can also show more subjective elements such as character and characteristics as well as points of view, values, prejudices and motivation. Rich pictures can both record and evoke insight into a situation. They can be regarded as pictorial ‘summaries’ of the physical, conceptual and emotional aspects of the situation at a given time. They are drawn both prior to analysing a situation, when it is unclear which parts are particularly important and as an inquiry proceeds as a means to monitor what, if anything, has changed.

Rich pictures can be invaluable in communicating issues between groups of people where there are cultural or language differences.

Drawings, pictures and text can provide the basis for the shared understandings needed to enable further dialogue (and perhaps further rich pictures). A rich picture offers a great deal of scope for creative thinking and freedom in how you represent your ideas. A lack of drawing skill is no drawback as symbols, icons, photographs and/or text can be used to represent different elements.

Here is an example of a rich picture, drawn for the Metropolitan Police to explore vice in the West End of London:

Drawing rich pictures is often done most effectively in groups so that different individuals can share their perceptions of the problem situation.

They are made up from:

- pictorial representations

- key words

- cartoons

- sketches and symbols

- title

It is usually best to avoid too much writing, whether as commentary or as ‘word bubbles’ coming from people’s mouths, although some people find it easier to use short phrases than to try to come up with a pictorial representation of some complex ideas.

Guidelines to Developing Rich Pictures

- A rich picture is an attempt to assemble everything that might be relevant to a problem situation. You should try to represent every observation that occurs to you.

- Use words only where ideas fail you for a sketch that encapsulates your meaning.

- Do not seek to impose any particular style or structure on the picture. Place the elements on your sheet of paper wherever seems appropriate. At a later stage, you may find that the placement itself was significant.

- If you ‘don’t know where to begin’, the following sequence may help to get you started:

- first look for the elements of structure in the situation (these are the parts of the situation that change relatively slowly over time and are relatively stable – the people, official organizations, elements of the landscape, perhaps)

- next look for elements of process within the situation (these are the things that are in a state of change – the activities that are going on)

- then look for the ways in which the structure and the processes interact.

- Avoid thinking in systems terms: that is, using ideas like ‘Well, the situation is made up of an ecosystem, an agricultural production system and a planning system.’

- Your picture should include not only the ‘hard’ factual data about the situation but also the ‘soft’ subjective information.

- Look at the social roles of those involved within the situation, and at the kinds of behaviour expected from people in those roles. If you see any conflicts, indicate them.

- Finally, include yourself in the picture, or, if you are doing it as a member of a group, include the members of the group. Make sure that your roles and relationships in the situation are clear. Remember that you are not an objective observer, but someone with your own set of values, beliefs and norms that colour your perceptions.

You will realise that your rich picture is simply a pictorial expression of one subjective appreciation of the nature of the problem situation.

The following YouTube video gives an example of the power of rich pictures in generating ideas. Bear in mind that your rich pictures do not need to aim to be this professional.

Required

10 mins

40 min

Read only Chapter 2, p 9 – 42.

If systems thinking could be so helpful why isn’t it utilised more widely? What could you do to implement it if you felt so inclined?

Donella Meadows was an American Environmental Scientist whose book ‘Thinking in Systems’[6] offered advice in terms of the leverage points for intervening or influencing systems. Her writing reminds us that while we might be able to intervene in some ways to influence systems, we can often not control them. Many writers cite her use of the metaphor of ‘dancing’ to reinforce how we might best engage with systems that we are seeking to understand or influence:

We can’t control systems or figure them out. But we can dance with them! I had learned about dancing with great powers from whitewater kayaking, from gardening, from playing music, from skiing. All those endeavors require one to stay wide-awake, pay close attention, participate flat-out, and respond to feedback. It had never occurred to me that those same requirements might apply to intellectual work, to management, to government, to getting along with people.

Living successfully in a world of systems requires more of us than our ability to calculate. It requires our full humanity – our rationality, our ability to sort out truth from falsehood, our intuition, our compassion, our vision, and our morality”.

(Meadows, 2001, p.58-63)[7]

The call for all of us is to open our minds to the benefits of thinking systemically in seeing patterns, understanding consequences and expanding our understandings in our own world. In the Australian context, the APS makes some suggestions about promoting systems thinking on our context in the reading, which follows:

30 min

Read Chapter 12.

If you were given the task of assisting your agency to deal with complexity, how would you implement systems thinking?

Start Preparing for Assignment Two

Consider Assignment 2 and the point of view you have adopted.

- Can Systems thinking contribute to your analysis?

- Can you notice boundary issues, adaptive mechanisms, and complexity.

Recommended

Boundaries of Soft Systems

For a more detailed yet understandable analysis of systems and the role played by boundaries you may find the following paper useful.

Read Chapters 8 to 11.

Implementation of systems thinking

Chapman has some thoughts on the matter and, in the final part of the pamphlet, he introduces concepts of organisational learning, feedback loops, and explores obstacles to the implementation of systems thinking.

Note that in his pamphlet, Chapman uses the phrase ‘complex adaptive systems’. In complexity theory, these days, it is more usual to use ‘complex evolving systems’ – to reflect more clearly the fact that complex systems don’t just adapt to external circumstances but themselves evolve as a result of internal changes.

Deeper Learning

45 mins

The following article looks at the use of Systems Thinking in the British Civil Service. It is an empirical study, with the individual experiences of civil servants coming through very clearly. The paper discusses conceptualisations of Systems Thinking, levels of knowledge and interest, uses and experiences, and challenges for its wider adoption.

Nguyen, L. K. N., Kumar, C., Bisaro Shah, M., Chilvers, A., Stevens, I., Hardy, R., Sarell, C. J., & Zimmermann, N. (2023). Civil Servant and Expert Perspectives on Drivers, Values, Challenges and Successes in Adopting Systems Thinking in Policy-Making. Systems, 11(4), 193-

- Checkland, P, and Scholes, P. (1990). Soft Systems Methodology in Action. Chichester, West Sussex, UK. ↵

- Checkland, P & Poulter, J. (2020). Soft Systems Methodology. In M. Reynolds & S Holwell (eds) Systems Approaches to Making Change: A Practical Guide. (pp. 201-253) ↵

- Zokaei, K., Elias, S., O’Donovan, B., Samuel, D., Evans, B. & Goodfellow, J. (2010). Report for the Wales Audit Office: Lean and Systems Thinking in the Public Sector in Wales. Lean Enterprise Research Centre. Cardiff. ↵

- Mason, R.O., & Mitroff, I.I., (1981). Challenging Strategic Planning Assumptions: Theory, Cases and Techniques. NY: Wiley. ↵

- Hummelbrunner, R. (2011). Systems Thinking and Evaluation. Evaluation. 17395. ↵

- Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea green publishing. ↵

- Meadows, D. (2001). Dancing with systems. Whole Earth, 106, 58-63. ↵