Module Five: System Thinking

TOPIC 5.2: What are the different kinds of systems?

Simple and Complex systems

How do we know if our system is simple or complex? This topic will provide some guidance in determining this important question.

A system, in an organisational frame is an integrated amalgam of people, product, and processes that provide a capability to satisfy a stated need or objective. Think about the health care system, the economy, or the banking system.

Often the description of phenomena is quite hierarchical and non-connected. When you do ‘systems thinking’ you are trying to approach an issue, problem or opportunity by locating patterns and relationships, and learning how to reinforce or change these to fulfil your vision or mission.

For example, we have seen through the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety that there is no easy fix to problems people experience with aged care (Duckett & Stobart, 2021).[1] As in so many areas, we need to see all the inter-relationships and patterns before any useful recommendations can be made. The focus should be on the relationships between things or the parts.

Snowden & Boone’s (2007, p. 72-3)[2] taxonomy of systems suggests that if your problem involves a ‘simple’ system then there may be more chance to ensure a cause and effect outcome, because there are fewer variables, and you may have more control over those variables due to proximity, time, and/or resources. If your problem involves a ‘complex’ system your inputs may create perturbations in the system, which set it, and perhaps other systems, off in a way never imagined (unintended consequences). Being able to recognise what type of system you are involved in can assist you to choose the correct tool(s), in the same way you can choose appropriate golf clubs, if you know the length of the green and the type of conditions. (Doesn’t always mean you have a perfect outcome – sadly).

The Stacey Matrix and Complex Adaptive Systems

The Stacey Matrix has relevance in a public sector, or political, context. First, it may pay us to gain some insights into a complex adaptive system, i.e. one that has independent variable actors, which create change in the system.

A complex adaptive system has three characteristics. The first is that the system consists of a number of heterogeneous agents, and each of those agents makes decisions about how to behave. The most important dimension here is that those decisions will evolve over time. The second characteristic is that the agents interact with one another. That interaction leads to the third—something that scientists call emergence: In a very real way, the whole becomes greater than the sum of the parts. The key issue is that you cannot really understand the whole system by simply looking at its individual parts. (Mauboussin, 2011, p.89)[3].

Complex adaptive systems, therefore, are emergent in that they evolve and are intractable. One definition of a complex system is one in which there is an inability of a single perspective to describe the system. Meaning it takes a complex language and no single observer can understand it. ‘Intractable’ in so much that it is on a journey and there is no faster way to know (predict) the future. You have to go through it.

What does systems thinking look like?

Again, we will visit Chapman and the next section of his reading, which is concerned with distinguishing between simple and complex problems; in Chapman’s words “difficulties” and “messes”.

A core message of the reading is that “messes”, due to their complexity, will often be interpreted very differently by various stakeholders. The ability to integrate multiple perspectives about a complex problem is an important attribute of successful systems thinking.

Think for example, about the number of ways we could consider energy policy in Australia. We could look from an environmental, social or an economic perspective. We need to be able to consider all of these in order to have policy that is ‘sustainable, reliable and affordable’ (General Assembly of the UN).

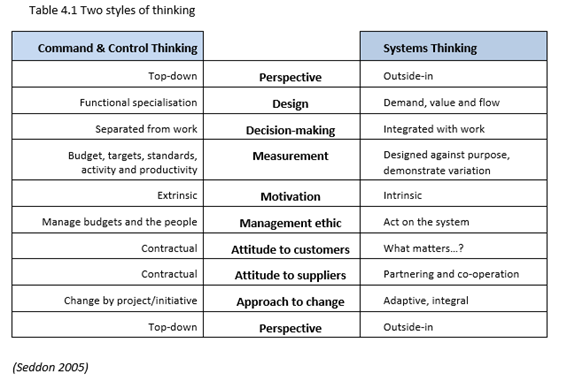

Pragmatically, for public servants, the following table (Table 4.1)[4] contrasts the two styles of thinking, required.

Obviously, in the systems thinking approach it requires you to be holistic in both your view and your behaviour.

Having determined that there are different styles of thinking it might be timely to remind ourselves that the APS believes that in the public sector there is room for a number of styles when dealing with wicked problems.

Recommended

Stacey Matrix

The Stacey Matrix enables you as a practitioner to select the appropriate management actions in a complex adaptive system based on the degree of certainty, and level of agreement on the issue in question.

As you read the recommended reading, consider the following:

- If you believe a government department is a complex system:

- Can you unscramble an egg when you re-engineer the bureaucracy?

- What is missing?

- What supports are dysfunctional?

- What collateral damage has it done to connecting and related systems

- And, second, in the area of policy:

- What do we need to have in place in order to influence policy outcomes if it is a complex system as distinct to a complicated system?

Systems Thinking

Using Seddon’s table as a guide:

- What style does your agency adopt?

- What do you notice as benefits and weakness?

- What do you believe are the benefits and weaknesses of the alternative style for your workplace/situation?

- What style do you, personally, attempt to adopt? Why?

- If you notice both styles – what circumstances do you see that determines the use of a particular style?

- Duckett, S. & Stobart, A. (2021, March 1). 4 key takeaways from the aged care royal commission’s final report. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/4-key-takeaways-from-the-aged-care-royal-commissions-final-report-156109 ↵

- Snowden, D.J. & Boone, M.E. (2007). A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review. November. ↵

- Mauboussin, M. J. (2011). ‘Embracing Complexity’, Harvard Business Review. Sept 89 – 92. ↵

- Seddon, J., (2005). Freedom from Command and Control: Rethinking Management for Lean Service. N.Y.: Productivity Press. ↵