Module Four: Globalisation

TOPIC 4.3: Small vs Big Government

What is the role of government in stimulating the economy?

We often hear that government stands in the way of ‘business’, or is part of a ‘nanny state’ and without government interference, less regulation, society, the country, the economy would be better off.

What is a small government? Conversely, what is ‘big government’ and what political parties promote one over the other? And, do the policies of those promoting small government actually result in reducing the size of government?

Queensland Senator Matt Canavan was a member of Cabinet in the Turnbull and Morrison Governments and Minister for Resources and Northern Australia from 2016 to 2020. In his maiden speech to the Senate on 16 July 2014 he called for more support for small, farmers, small business and families.[1]

“I want try to make sure all Australians can choose their own job, buy their own home, start their own business or have their own family. For each small Australian to be big, they must be free from big government, big banks, big unions and big corporations,” Senator Canavan said in his maiden speech in the Senate.

“Small farms and small businesses allow more Australians to have a stake in their country. Smaller towns provide greater community spirit and become their own hives of innovation. The smallest social unit of society, the family, is the most important one for us all”.

“To protect the small, we need to create more jobs, boost productivity, protect small business and make it easier for families to buy their own home.”

In his speech, Senator Canavan supported stronger competition laws, superannuation changes and income splitting, and he called for a “national productivity agenda”.

What is ‘big and small government’?

The size of government could be considered from an economic, politico-legal or philosophical perspective.

Typically, when people use the term ‘big government’, they are often describing a government that is physically large and expensive to run. For example, thinking about how ‘big’ government is in Australia we could compare different government spending as a percentage of the nation’s GDP. International Monetary Fund data reveals that on average over the decade from 2011-2021 (latest available comparable data) total government expenditure in Australia was 38.5% of GDP. This was more than the US (37.3%) the same as NZ (38.4%) but significantly less than Sweden (49.3%), Italy (51%) and France (57.3%). This might seem intuitively correct to us here in Australia as many US politicians are vocal about smaller government and many European countries are noted for their government funded generous welfare and pension systems. However, China the 2nd largest economy in the world and 10 times that of Australia’s, had average government expenditure of less than 32% of its GDP over the same period. Some might argue that from an economic perspective, Australia has ‘bigger government’ than China.

From a political and philosophical perspective ‘big government’ is a term generally used in a pejorative manner by factions on the political right (or by those who believe in individual freedoms) to describe a government that is too intrusive in too many areas of individual citizens’ lives. This could include criticisms of governments that try to exercise too much control over business, but also includes criticisms of governments that aim to provide too much welfare, or are too prescriptive on preventative health issues, for example by trying to influence behaviour on smoking or eating.

Small government minimises its own activities. It is an important topic in libertarianism and classical liberalism.

According to financial commentator Michael Lewis (2022):[2]

“The term ‘big government’ stimulates plenty of images and emotions, and they’re generally negative. Words like ‘bureaucratic’, ‘inefficient’, ‘intrusive’, and even ‘corrupt’ are often associated with the term. Economists charge that big government interferes with the mechanisms of free enterprise. Libertarians believe it seeks to control private or personal freedoms guaranteed by the ‘natural law’ eloquently philosophized by John Locke and formalized in the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights. And politicians claim big government lacks checks and balances on its exercise of power, leading it to represent special interests to the detriment of its citizens.

“Small government, on the other hand, is generally believed to lead to a more efficient and flexible system. ‘Getting government off our backs’ or ‘getting government out of the way’ are cries to return to the low-tax, no-regulation beliefs of the American Revolutionary period. The size of government envisioned by the country’s founders sought to cast off tyranny and empower small businessmen and entrepreneurs.

“Small government was best summarized by the principal author of the Declaration of Independence and third President of the United States Thomas Jefferson when he claimed, ‘That government is best which governs least, because its people discipline themselves.’ Meg Whitman, former CEO of eBay, current CEO of Hewlett-Packard, and one-time Republican candidate for Governor of California described it as ‘making a small number of rules and getting out of the way. Keeping taxes low. Creating an environment for small businesses to grow and thrive.’…”

The debate about government scale began with the ‘economic rationalists’ who believe the market best determines the choices to be made in economic terms. The government of some countries believe in heavy involvement (e.g. China, Russia, and Japan) with centrally planned economies, others in more restrained involvement (US, Britain). The debate is important for public servants to understand firstly, because the efficiency of the public sector itself is a factor in international competitiveness; secondly, appropriate policy settings to support national competitiveness are required because markets are subject to global competition; and, thirdly, much of the pressure for public sector reform discussed in Module 6 is driven by the debate.

In the Australian context, the Coalition Government in 2014, in an attempt to create smaller government proposed to extract itself from health and education matters in favour of the States and Territories, to deregulate universities, and introduce a co-payment to Medicare.

These proposed changes were very controversial when announced and caused significant pushback from both the jurisdictions and various interest groups.

So, is government in Australia ‘big or small’?

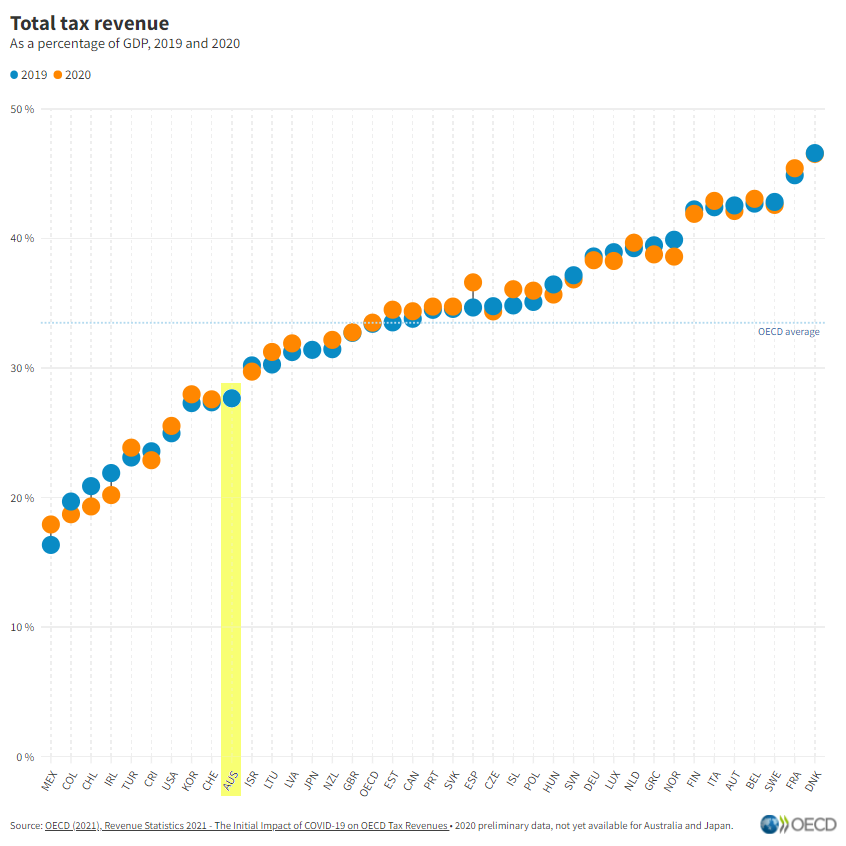

One way to measure how big or small a government is to look at the size of government programs relative to the GDP of the nation. Despite the popular misconception that Australia taxes are very high by world standards, since the 1960’s total taxes paid by Australians to all levels of government have been below the average rate for countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2022).[3] The OECD has 38 member countries including many comparable market-based democracies such as Canada, France, Germany, Italy, UK and USA. In more recent decades Australia has been general sitting around the bottom third of OECD countries for tax levels. The graph below illustrates Australia position as 10th lowest country for tax burden in 2020 and 2021.[4]

Big or small government and industry assistance

When we talk about big or small government, the target is usually social expenditure and impediments for businesses, and these are often decried as being ‘unsustainable’ to the budget. However sometimes this welfare is targeted to business and is often called ‘corporate welfare’.

According to Margaret McKenzie of the School of Accounting, Economics and Finance at Deakin University[5]:

“If ‘corporate welfare’ is taken to mean industry assistance, it is not a straightforward or transparent measure. Industry assistance is a combination of government expenditure, tax reductions and tariff protection, plus any regulatory measures, any or all of which may favour some activities over others. Such assistance may be granted according to the type of industry, or granted on an ad hoc basis to specific companies, often big ones. Industry assistance also varies counter-cyclically, increasing with the GFC and drought, offering a beneficial stabiliser effect on the economy.”

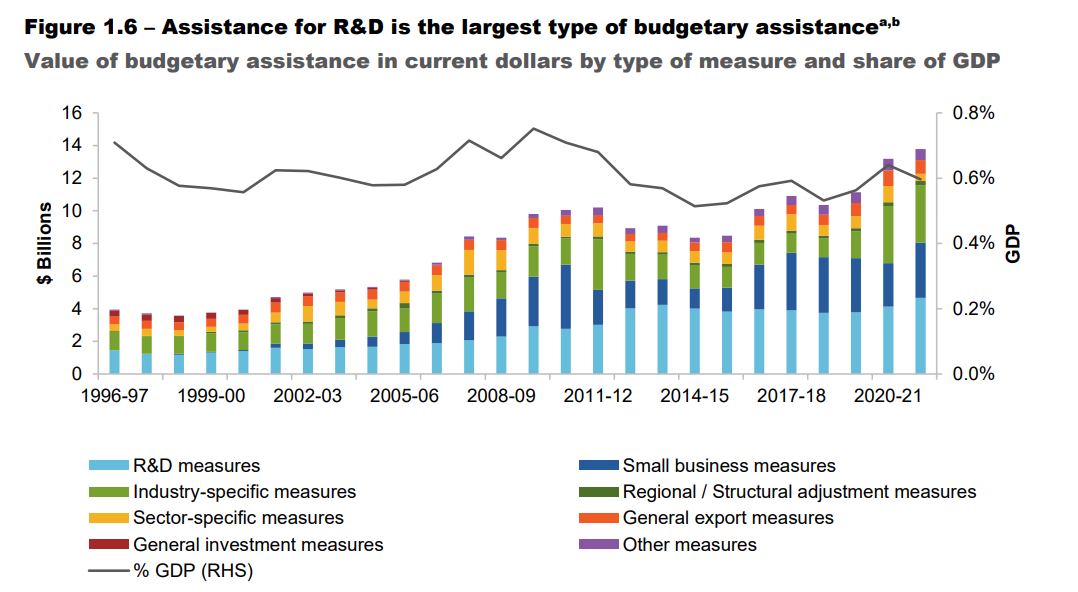

According to the Productivity Commission, assistance to Australian industry was $13.8 billion in 2021-22 and increase of almost half a billion dollars on 2020-21. This is part of global trend of ‘overt industry policy’ with many large economies favouring selected domestic industries through subsidies, local content rules and trade barriers or as they put it ‘old-fashioned protectionism’. The Commission’s view is that it is in Australia’s interests as a small open economy to have global economic integration and low trade barriers (Productivity Commission 2023a).[6] The graph below shows over 25 years of industry assistance from all levels and political persuasions of government.

Source: (Productivity Commission, 2023b, p13)[7]

Comparing Australia to other countries in social expenditure

A refrain across many OECD countries is that with the people living longer, public spending on the age pension and associated benefits has been too high and is unsustainable as a % of GDP. Many OECD countries have been progressively raising the pension age with the 2021 average OECD pension age of 64 years predicted to rise to 66 years by the mid 2060’s (OECD 2021).[8] Australia has moved faster than most OECD countries with the current pension age now 67 following reforms by the Rudd and Gillard Labor governments in 2010. Later plans by the Abbott and Morrison Coalition governments to raise the age to 70 were abandoned (Chomik, 2018).[9]

According to the OECD, public expenditure on age pensions and associated benefits in 2019 (latest comparable data set) was 4.3% of GDP in Australia, 7.0% in Sweden, 7.1% in the US, and 13.5% in France. (OECD, 2023).[10] In 2009 Sweden was spending 1.2% of GDP more of public funds than the US however they have since started to raise retirement ages and plans to link them to life expectancy from 2026 (OECD 2021).

Recommended

50 mins

Reflection

Having considered the views of Senator Canavan and Robert Stiglitz and the data from the latest Productivity Commission report on industry assistance:

- Do you think that we need ‘bigger’ or ‘smaller’ government in Australia?

- Does the level of ‘corporate welfare’ change significantly based on the party in government at the time?

- Canavan, M. (2014). Maiden Speech to the Senate. Matt Canavan: Senator for Queensland. https://www.mattcanavan.com.au/maiden_speech_to_the_senate ↵

- Lewis, M. (2022). Big Government vs. Small Government – Which Is Ideal for the U.S.?. Money Crashers. https://www.moneycrashers.com/big-vs-small-government-ideal/ ↵

- OECD (2022), Table 3.1 - Total tax revenue as % of GDP, in Revenue Statistics 2022: The Impact of COVID-19 on OECD Tax Revenues, OECD Publishing, Paris, (Accessed on 20 February 2024). https://doi.org/10.1787/82ddda24-en ↵

- OECD (2021), “Tax-to-GDP ratios: Total tax revenue as a percentage of GDP. (Accessed on 20 February 2024). . https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/data-insights/tax-to-gdp-ratios. ↵

- McKenzie, M. (2014). Big ticket items missing from ‘corporate welfare’ discussion. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/big-ticket-items-missing-from-corporate-welfare-discussion-25909 ↵

- Productivity Commission. (2023a). Media Release 20 July 2023. Trade and assistance review exposes rising industry assistance. https://www.pc.gov.au/ongoing/trade-assistance/2021-22. ↵

- 6Productivity Commission. (2023b). Trade and assistance review 2021-22 Annual report series. https://www.pc.gov.au/ongoing/trade-assistance/2021-22/tar-2021-22.pdf. ↵

- OECD. (2021). Pensions at a Glance 2021: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ca401ebd-en. ↵

- Chomik, R. (2018). Retiring at 70 was an idea well ahead of its time, The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/retiring-at-70-was-an-idea-well-ahead-of-its-time-102704 Accessed 1 December 2023. ↵

- OECD. (2023). Pension spending (indicator). doi: 10.1787/a041f4ef-en (Accessed on 01 December 2023). ↵