Module Four: Globalisation

TOPIC 4.1: What is Economic Globalisation?

Economic globalisation in overview

For some readers, globalisation might mean ruthless exploitation by corporations and/or environmental pollution (mineral extraction in Africa), while for others it might be attributed to lifting millions of people out of poverty. Opportunity and risk is inherent in the interplay of economic globalisation with Australia.

Australia has exhibited a desire over many years to pursue trade policy in both a bilateral and multilateral fashion. Bilateralism recognises country to country agreements, whereas multilateralism covers agreements between many countries.

Multilateralism has been promoted through the United Nations and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) since 1947. The World Trade Organisation (WTO) replaced the GATT in 1995 with an expanded definition of trade to include services and intellectual property as well as goods. Multilateral agreements are designed to create clear trade rules, including processes for resolving disputes between signatories. The major shortcomings of this is the time taken to resolve disputes and the willingness of parties to abide by WTO rulings. Other prominent multilateral agreements include the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) countries and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Bilateral agreements often exist in parallel to multilateral pacts and may cover trading regulations for specific industries. A famous Australian bilateral agreement was int he 1950’s with Japan, less than 10 years after the end of World War II. In recent years bilateral agreements have often been termed as ‘Free Trade Agreements’ (FTAs).

As at January 2024 Australia has 18 FTAs in force with many of our major trading partners (e.g., China and USA) and with a number of other countries in the Asia-Pacific (e.g., Thailand, Singapore, New Zealand). It has concluded negotiations for the 12 nation Trans-Pacific Partnership and is in negotiations regarding 4 other FTAs including with the EU (DFAT, 2024).[1] Although trade is the focus for these bilateral and multilateral agreements, they often have significant cultural, political and regional cohesion objectives.

Australia has an exceptionally close economic, political and cultural relationship with New Zealand almost like a mini-EU in the Pacific. Through a combination of the Australia-New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement and other reciprocal agreements on immigration, pensions, health care, professional and educational qualifications and common technical standards there is free movement of people, goods, services and capital between the two nations.

While as we have already discussed globalisation is not a new concept it is, and has been, a controversial one.

You might have heard about the ‘Silk Road’, but you may not have been aware that the Romans were already lamenting the importation of silk because it was believed to be having a morally degenerate influence on Rome and, thus, the Roman Senate tried to outlaw the importation and the wearing of silk (Goldstein & Moss, 2011, p. 4)[2].

The influence of foreign ideas, cultures and products are, at times, still treated suspiciously or with caution by the home culture.

Drivers of globalisation

Bhagwati’s perspective on globalisation has two core themes: technological change and state action. Bhagwati (2007, p.3) defines economic globalisation as follows:[3]

Economic globalization constitutes integration of national economies into the international economy through trade, direct foreign investment (by corporations and multinationals), short-term capital flows, international flows of workers and humanity generally, and flows of technology.

The integration of Australia into the international economy will be explained in terms of trade, direct foreign investment and financial markets.

There is little doubt that globalisation has been largely driven by the twin forces of economics and technology. The other features – social and cultural – are less immediate but no less pervasive and will be dealt with in subsequent topics. Whilst it has been argued Australia has been subject to the vagaries of globalisation since, perhaps, its inception, there are changes. Looking at the changes in the types of trade, and our trading partners, provides a window into Australia’s changing relationship with the world and the implications it may have for our foreign and domestic policy.

Changing Trading Patterns

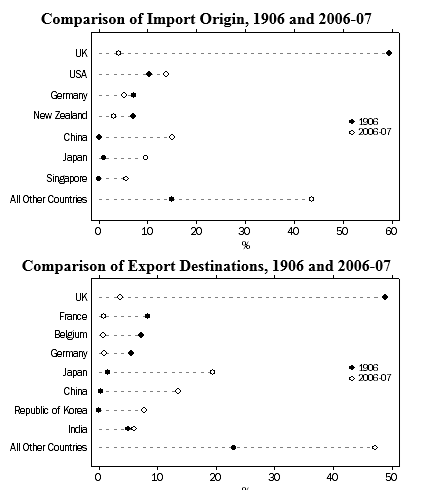

Australia’s international trade statistics have changed markedly over the past century in terms of the composition of imports and exports and the countries that we trade with.

From Federation in 1901 till the mid 1960’s Australia’s number one export was wool and if you refer to the diagram below you will note that the UK was Australia’s major trading partner. In 1906 the UK accounted for 59% of imports and 49% of exports, yet by 2006-07 only accounted for just 4% of both imports and exports. By the 1980s the focus of trade had shifted to Japan with coal our no. 1 export and by the new millennium the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) countries had collectively replaced the UK as our major trading partner, and accounted for 72% of Australia’s trade in 2006-07. Japan was our no.1 trading partner in the 2000s.

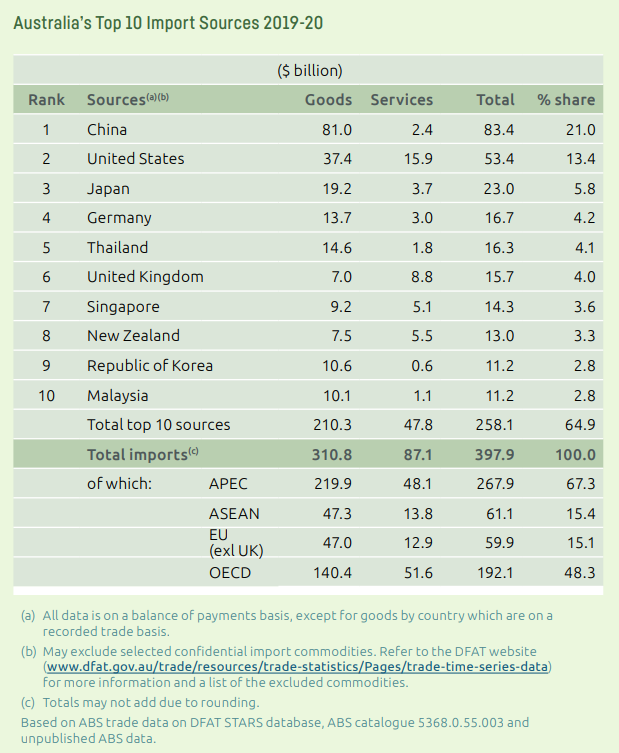

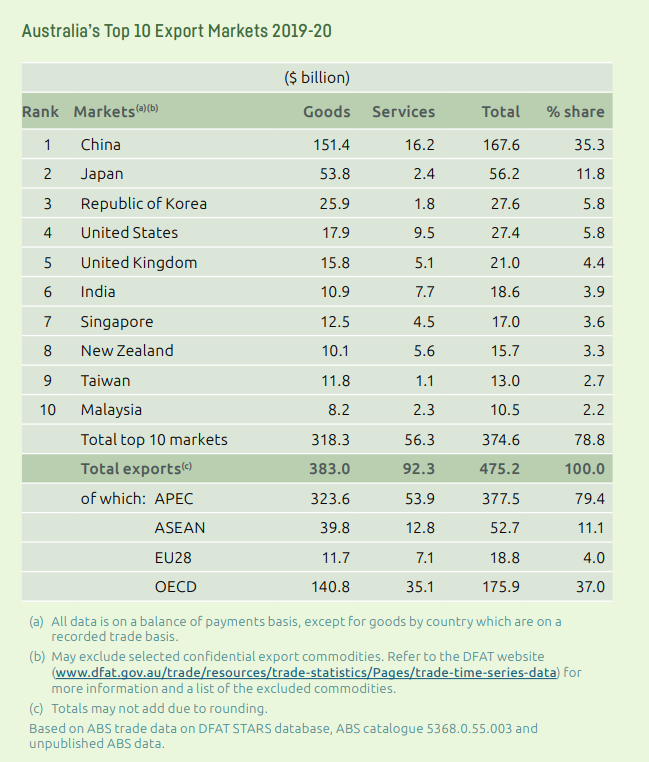

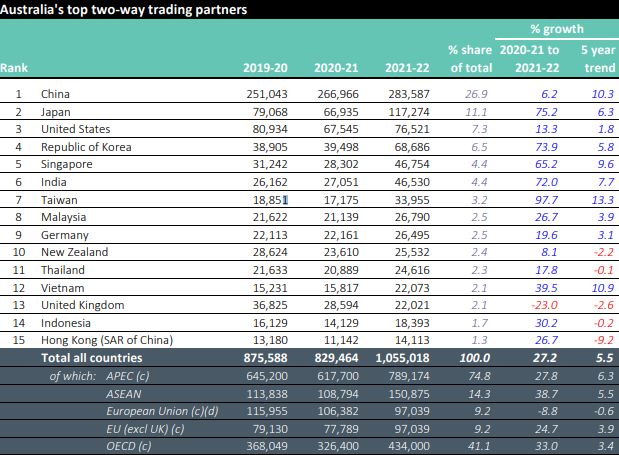

The pace and variation of trade relations continued the change in the next decade with China becoming our major two-way trading partner for both exports and imports with Japan no. 2. While iron ore and coal remained our top two exports, the growing importance of trade in services was evident with education and tourism where now consistently in our top 5 exports. Wool exports accounted for less than 1% of our exports in 2015 (Australian Parliamentary Library, 2016).[4]

In 2021-22 APEC countries accounted for 80% of our trade with the top five countries being China, Japan, USA, Korea and Singapore. The UK was ranked 13th (DFAT 2023a, Australia’s Trade in Goods and Services by top 15 partners).[5]

International trade statistics indicate a country’s economic strengths and challenges. They guide significant cross-border relationships and shape foreign economic policy. Spend some time reviewing the various charts presented below in the Required Readings to better understand the changing and challenging nature of international trade for Australia.

15 min

Note the shift in Australia’s trade dependence since 1906 in the following graphs. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, plus other disruptions in the middle East and Ukraine, the UK has dropped out of being in our top 10 trading partners. This highlights how easily trade relationships can be affected and the importance for countries to maintain a very wide range of trading relationships.

Given the shifts in our trading partners and the basket of exports and imports over time:

- Which trading partner and which exports and imports do you think will be number one for Australia and your jurisdiction in ten years’ time

- What implications does that have for public policy making for Australia’s governments?

Source: (ABS, 2007)[6]

Source: (DFAT, 2021, p. 18 & 41)[7]

Source: (DFAT, 2023a, p1)[8]

Australia’s Trade Policies

In order to provide confidence to Australian traders and to our trading partners, government is required to provide policy settings to guide trade dealings.

The Turnbull Government’s Foreign Policy White Paper in 2017[9] emphasised the importance of the free trade agreements (as well as other initiatives):

“Our openness to the world is vital to our economic strength. This connects our goods and services to larger, often faster growing markets. In turn, it enables Australia to benefit from the world’s best goods, services, people, capital and ideas to grow our economy and create jobs. Being open to trade and investment boosts competition, creates new wealth and supports high living standards.

We must guard against protectionism and build robust support for open economic settings by ensuring all Australians have the opportunity to benefit from our growing economy. Our trade and investment agenda will assist by boosting jobs and supporting higher living standards.”

The Albanese Government has not yet released a white paper laying out its strategic vision, position and objectives for trade, however the Minister for Trade and Tourism, Senator the Hon Don Farrell, released a statement in November 2022[10] outlining four principles to guide the government’s approach to trade and investment.

“Firstly, we have learnt the hard way, not to place all our trade eggs in the one basket.

Secondly, we must defend and reform the multilateral system.

Thirdly, we need to diversify not just who we trade with, but what we trade.

Finally, we believe the benefits of trade must be shared more fairly amongst the community.”

Has the change in government significantly altered Australia’s trade policies or are they fundamental the same with only minor changes in rhetoric?

Institutions governing world trade

To conclude this section on international trade, an understanding of the rules and institutions that guide and police world trade is important, and this is discussed through understanding GATT and WTO.

Following WWII, the US, and its principal allies, determined an informal agreement about the way countries would engage in trading. The principal issue was barriers to trade caused by tariffs placed on imported goods in an attempt to provide an advantage to the home team. This became known as the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT). While there was, an attempt to reach a formal agreement (the International Trade Organisation ITO) the US was determined not to be constrained by the negotiations required to reach the agreement and, possibly, perceived there was competitive advantage to be gained from bilateral agreements with vulnerable partners.

In more recent times there has been a reinvigoration of the drive to have a formal agreement through the World Trade organisation (WTO) established in 1995, with an emphasis on ‘free trade’ and multi-lateral agreements.

To this point the WTO has continued to operate on the GATT principles which are:

- Guidance by the principles of non-discrimination or unconditional acceptance of most-favoured-nation principle,

- Elimination of nontariff trade barriers (such as quotas) except for agricultural products and for nations in balance-of-payments difficulties, and

- Consultation among nations in solving trade disputes.

At its heart are the WTO agreements, negotiated and signed by the bulk of the world’s trading nations. These documents provide the legal ground rules for international commerce. They are essentially, contracts, binding governments to keep their trade policies within agreed limits. Although negotiated and signed by governments, the goal is to help producers of goods and services, exporters, and importers conduct their business, while allowing governments to meet social and environmental objectives.

The system’s overriding purpose is to help trade flow as freely as possible — so long as there are no undesirable side effects — because this is important for economic development and well-being. That partly means removing obstacles.

The point of showing the shift in patterns of trade is to remind you where Australia’s interests may have shifted in terms of protecting markets, supporting struggling governments, creating alliances, learning to understand cultures to improve diplomacy. Our reliance on equity and overseas borrowings is also a feature of global forces and requires creative governance to manage in our national interest.

25 min

Take a sheet of paper and write down what you think are areas of your work that are affected by what is happening in other countries.

It’s okay if nothing comes immediately to mind. Think more broadly about other areas of the department or agency. (Climate change, human rights, world heritage sites, wars…)

Financial markets

Trade is just one aspect of the global economy. What about financial markets? We need to ask the question: in what ways does the global economy affect us as citizens and by extension, in what ways does it affect our work?

The financial market will be discussed in terms of borrowing, international equity markets and the impact of confidence in the wider market using the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the impact of crippling sovereign debt, still observed more than a decade later, in a number of European economies, notably Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain.

Debt market: Banks have to borrow money from the market and international markets are one of the places they go to borrow. The cost of capital for banks either increases or decreases, and thus, borrowing becomes; either more or less, expensive, which then, either leads to; more or less borrowing and, thus; affects spending and savings behaviour for households and businesses.

Equity markets have two effects. They can either:

- Reduce or increase the capacity of businesses to raise new share capital, or

- Generate a ‘negative or positive wealth effect’, particularly on people with superannuation and other share investments, who are in, or approaching, retirement.

To conceptualise the interconnected nature of Australia‘s economy with the world, let’s look at the Australian equity market’s reaction to international financial crises from 1929 to 2007. A major issue with international markets is that Australia’s interdependence means we are impacted positively and negatively by large international markets.

A lack of confidence in the future can drive our market down.

According to the RBA (Reserve Bank of Australia), the most obvious manifestation to the general public of the impact of the financial crisis on Australia has been the decline in value of the local stock market. From its peak in November 2007 to the lows reached earlier (in 2014), the local market declined by 54 per cent. This fall compares to the peak-to-trough decline of 57 per cent in the US market, 61 per cent in Europe and 60 per cent in the Japanese market. Thus, the impact on the Australian share market was similar to that in other countries.

In the light of the criticism in the US, of the role played by poor regulation in the financial industry; the concentration of the industry into large entities, which governments cannot afford to allow to fail; and, the international securitisation of the industry, there has been increased scrutiny of the role played by regulation in international governance.

Multinational Companies and Direct Investment

A persistent issue for government is the role played by multi-national companies and the role of direct investment by foreign companies in Australia.

Multinational corporations (MNCs), also known as multinational enterprises (MNEs) or ‘transnational corporations’ are firms that own, control or manage production and distribution facilities in several countries. They have offices and/or factories in different countries and usually have a centralised head office where they coordinate global management.

2018 analyses by the OECD showed that MNCs generate half of global exports, a third of global production, almost one-third of world GDP and one fourth of employment (OECD, 2018, pp. 5-6)[11]. The annual revenues of many MNCs exceed the GDP of many countries and thus MNCs have great political and economic power and influence.

Global action through inter-governmental forums of nations with significant economies (G7 and G20 has been forthcoming with the aim of restricting the ability of multinational corporations to avoid taxation in jurisdictions where profits are earned. Agreement has been reached in principle to ensure that companies pay at least a modest amount of tax (approximately 15%) on profits earned. In the 2023-24 Budget the Commonwealth government announced that it was progressively implementing the 15% minimum tax rates on MNC from 1 January 2024 (ATO, 2023).[12]

There are a multitude of reasons why MNCs have a competitive advantage vis-à-vis purely national firms that may explain their proliferation and their great importance today.

Global action through inter-governmental forums of nations with significant economies (G7 and G20) has been forthcoming with the aim of restricting the ability of multinational corporations to avoid taxation in jurisdictions where profits are earned. Agreement has been reached in principle to ensure that companies pay at least a modest amount of tax (approximately 15%) on profits earned. In the 2023-24 Budget the Commonwealth government announced that it was progressively implementing the 15% minimum tax rates on MNC from 1 January 2024 (ATO, 2023).

Countries are keen to attract MNCs to locate in their country. However, in addition to the potential benefits, there are also concerns about negative outcomes, such as:

- Job losses in Australia

- Export of advanced technology out of Australia

- Transfer pricing to avoid Australian taxation

While some countries might feel a loss of sovereignty, how well a host country deals with the potential negative effects of MNCs depends on its domestic policies. For example, the complaint that many MNCs conduct their research in their home country is being addressed in Australia by offering MNCs research and development tax incentives to conduct the research in the host country.

Australia and Foreign Direct Investments (FDI)

Australia has always relied heavily on foreign investment and has consistently been one of the top 20 global destinations for foreign direct investment (FDI) since the 1990s. For the last decade Australia has almost always been a top 10 destination for FDI and, despite the slowdown in world economic activity due to the pandemic, attracted almost US$440 billion of direct investment in that time. It often attracts more FDI in a year than comparable economies with much bigger populations such as Canada, Italy, France and Germany. (UNCTAD, 2014, 2018, 2019, 2023, Annex table 1).[13][14][15][16][17]

The pandemic showed Australia’s economic strength, vulnerability and resilience in attracting a steady flow of FDI. Over the three years to 2019, Australia attracted a total of US$153 billion in FDI flows, up over 15 per cent from US$132 billion over the previous three years. This continued impressive growth continued the decade long upwards trend to raise Australia’s share of total global FDI inflows to 3.3%. The pandemic had a major impact on FDI in the following three-year period (2020-2022) with a 21% reduction globally, 37% reduction in Australia and 51% reduction across the developed economies. By 2022 Australia had recovered well, attracting almost 5% of total global FDI for that year. This put us back on our decade long trend compared to the developed economies as a whole that were still at half their long-term trends (UNCTAD, 2014, 2018, 2019, 2023, Annex table 1).

Apart from the economic benefits as outlined above the implications of economic globalisation for government is that it makes it more difficult for governments to influence the activities of companies who either operate here, or own enterprises here, but have headquarters elsewhere. To whom do they belong, to whom are they accountable, and to whom do they owe allegiance? The traditional notion of nation states being the basis of governance starts to be questioned. In addition, it is more difficult to extract taxes and determine value and real costs of Australian operations.

With our focus on Asia, in this course it is noted that over the last few years concern has been raised in the media about “China buying up large areas of Australian farmland”.

Recommended

Reflection

Provide feedback to the Prime Minister through your one paragraph assessment of what has happened to Australia’s trade picture during the last century and how favourable or vulnerable the picture now looks.

What are the implications for the bureaucracy?

Reflection

Consider the policy of the Coalition governments

- Does it signal a change in geographic orientation?

- Has the coalition progressed Free Trade?

- How do you think recent geopolitical events (change in US residency, rise of China, Brexit) will affect Australian trade policy?

Regulation (25 mins)

The following reading outlines the historical paradigms and provides some indicators to the future, and ideas for public policy makers.

Globalization (15 mins)

Reflection

Given your exposure, through either the video or the review, to the thinking of Stiglitz, how do you believe Australia is placed to handle globalization at the moment? Why so?

Multinational Corporations (6 mins)

The following video provides a summary of what foreign direct investment (FDI) is, and the conditions in which MNCs flourish.

Australian Foreign Investment (30 min)

On balance, do you think the fear of a ‘Chinese takeover’ warranted? And what is the emotive difference between FDI from the US and China?

Deeper Learning

If you are interested in pursuing this topic at length, then Bhagwati’s (2007) book, In Defense of Globalization, is strongly recommended.

It provides a philosophical and historical overview of the evolution of globalisation and the rise of the anti-globalisation movement. It reiterates the principles of trade theories and other important economic concepts in an eloquent non-textbook style. Bhagwati wrote the book in response to the anti-globalisation movement that erupted into violent protests in early 2000, starting with the protest against the World Trade Organisation (WTO) meeting in Seattle, in on 1st December 1999. His original 2004 edition of the book garnered a wide range of commentary, and the 2007 edition explores and responds to this commentary, particularly a number of economic and social impacts on different groups.

- DFAT, (2024). Australia's Free Trade Agreements. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved February 14, 2024, from https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/trade-agreements ↵

- Goldstein, N., & Moss, J. G. (2011). Globalization and free trade. Infobase Learning, ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/detail.action?docID=877715. ↵

- Bhagwati, J. (2007). In defense of globalization : With a new afterword. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. ↵

- Australian Parliamentary Library. (2016) Australia’s Trade. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BriefingBook45p/AustraliaTrade. Downloaded 20 December 2023. ↵

- DFAT. (2023a). Australia's Trade in Goods and Services by top 15 partners. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra. www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/australias-goods-services-by-top-15-partners-2021-22.pdf. Downloaded 3 Jan 2024. ↵

- ABS. (2007). 100 Years of International Trade Statistics. International Trade in Goods and Services, (October 2007). https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/0/618AFF5416C64078CA2573E9001016FE?OpenDocument#:~:text=The%20UK%20was%20Australia's%20major,Australia's%20trade%20in%202006%2D07 ↵

- DFAT. (2021). Trade and investment at a glance 2021. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra. https://www.dfat.gov.au/publications/trade-and-investment/trade-and-investment-glance-2021. Downloaded 14 February 2024. ↵

- DFAT. (2023a). Australia's Trade in Goods and Services by top 15 partners. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Canberra. www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/australias-goods-services-by-top-15-partners-2021-22.pdf. Downloaded 3 Jan 2024. ↵

- DFAT (2017). 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/2017-foreign-policy-white-paper.pdf ↵

- Farrell, D. (2022). Trading our way to Greater Prosperity and Security, 14 November 2022. https://www.trademinister.gov.au/minister/don-farrell/news/trading-our-way-greater-prosperity-and-security ↵

- OECD. (2018). Multinational enterprises in the global economy. Heavily debated but hardly measured. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/industry/ind/MNEs-in-the-global-economy-policy-note.pdf ↵

- ATO. (2023). Implementation of a global minimum tax and a domestic minimum tax. ATO New legislation - International. Australian Taxation Office. https://www.ato.gov.au/about-ato/new-legislation/in-detail/international/implementation-of-a-global-minimum-tax-and-a-domestic-minimum-tax ↵

- Note on the following data sources (14 - 17): The UNCTAD World Investment Report series often revises data sets one or two years after publication. The data sets were constructed, were possible, using data for a particular year that had been republished at least once. ↵

- (UNCTAD, 2014, p. 205) United Nations Conference on Trade and Development World Investment Report 2014: Investing in SDGs: An Action Plan. Annex table 1. FDI flows, by region and economy, 2008–2013. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2014_en.pdf ↵

- (UNCTAD, 2018, p. 184). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development World Investment Report 2018: Investment and new industrial policies. Annex table 1. FDI flows, by region and economy, 2012-2017. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2018_en.pdf ↵

- (UNCTAD, 2019, p. 212). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development World Investment Report 2019: Special economic zones. Annex table 1. FDI flows, by region and economy, 2013-2018. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2019_en.pdf ↵

- (UNCTAD, 2023, p. 196). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development World Investment Report 2023: Investing in sustainable energy for all. Annex table 1. FDI flows, by region and economy, 2017-2022. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2023_en.pdf ↵