Module Two: How do we understand public value?

TOPIC 2.5: What is Responsive and Responsible Decision-Making?

Responsive and responsible in context

Within the paradigm adopted by the public administrator is embedded the notion of what being responsive means, and what evidence should be used when making a decision. Frameworks offer a rounded model of what needs to be considered when making appropriate decisions. Modern government is expected to be guided by ‘evidence’, which can support rational and transparent decision-making. These issues are discussed in this Topic 5.

Frameworks

Frameworks are important to ensure there is some stability and continuity within and across government. Where they don’t exist, the Government, for example, could find itself competing across Departments for staff and raising the price of labour (E.g. various Departments might require social workers to oversight safety, mental health compliance, allied health assessments, prisoner rehabilitation and, in contesting for recruits, artificially lift the price by bidding for a scarce commodity); or, agreeing through workplace bargains to pay staff on similar pay points more in the most affluent Departments than staff in less affluent. This can lead in some cases to staff pay inequities of many tens of thousands of dollars. A framework can be considered similar to a strategy or plan about the way government intends to operate. Examples are:

- People or workforce framework

- Policy framework

- Financial management framework

- Performance framework

These will be treated in more detail in subsequent Units.

10 min

- In your position within the public bureaucracy, what do you consider to be the ‘people framework’ by which you are treated and by which you must manage your people?

- If you have financial responsibilities what is the ‘financial framework’ in which you are required to operate?

Evidence-based decision-making

To help you think about the importance of evidence-based decision-making, we use the case of the Home Insulation Scheme roll-out. Who made the decision to roll out insulation as a means of distributing money to the community and which led to hundreds of house fires and the deaths of four young men?

What aspects of the decision making process went wrong? What evidence was assessed by those making the decision? What is reasonable risk for the public sector? What relationship was there between the decision to privatise training for installers and a treatment for GFC? Government rises and falls upon its decision-making ability. What models should it adopt?

In some cases, public sector decision-making is determined by numerous paradigms. For example, the political persuasion of the party in power; small ‘L’ liberal or alternative views of the world;

One phrase that says a lot in the modern public sector is the need to undertake ‘evidence-based decision-making’, which is contrasted with ‘opinion-based’ or ‘beliefs-based’.

Public Policy Theory

The previous section hints at an issue which is worth considering further. In an ideal world, policy would be done once: it would be perfectly developed, based on solid evidence, then perfectly implemented and achieve exactly what is intended. Yet this rarely happens. The reasons for this are many and complex, but the academic field of Public Policy sheds light on some important issues.

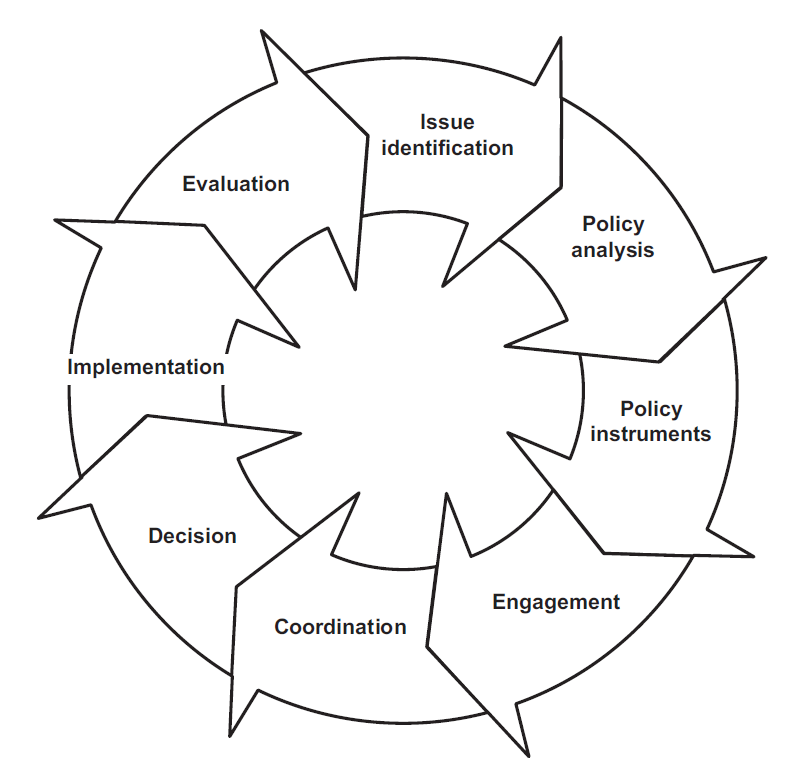

You may be familiar with the policy cycle[1], which is a highly-stylised and idealised (perhaps naïvely optimistic) representation of policymaking. There are many variations, but the version below is one of the best known in Australia.

The Australian Policy Cycle (Althaus, et al, 2023)

Despite still being widely-used as a tool to understand public policy, few people believe it represents reality in any meaningful way. It would be surprising if anyone reading this document has regularly seen policy going neatly through these steps. Since the 1950s, the policy cycle model has been challenged more and more by alternative ways of understanding policy development.

The most obvious criticism of the model is that it relies on a perfect world of time, resources and personnel. Yet common-sense says this is rarely possible. In the 1950s, Herbert Simon coined the term “bounded rationality” to describe the fact that policy makers are generally working to tight time constraints, with limited staff, incomplete information, patchy data and other constraints (Birkland 2020; Cairney 2020)[2][3]. More broadly, humans have a limited brain capacity and governments can only focus on a few things at once. Simon’s answer to this is that policy makers should still strive for perfect (“rational”) policy but ultimately need to “satisfice” – that is, be content with policy answers that are “good enough” given the constraints.

In response to Simon’s analysis, Charles Lindblom argued there was little point in even striving for perfect policy. While fully agreeing with Simon’s points about bounded rationality, Lindblom added some of his own. He claimed, firstly, that policy often has to be developed despite a lack of clearly-stated goals, and secondly, that it is impossible to overcome the political dimensions of policy development. Given this, Lindblom claimed, policy makers should abandon attempts at grand policy-cycle style processes and perfect policy. Instead, “incrementalism” or “the science of muddling through” is the answer, which means taking small steps as and when an opportunity arises which over time can improve policy or create big change (Birkland 2020; Cairney 2020).

Perhaps the polar opposite of the policy cycle is John Kingdon’s Policy Streams model (also known as the Multiple Streams model (Birkland 2020; Kingdon 2011)[4]. Developed from Cohen, March and Olsen’s even more radically chaotic Garbage Can model, Kingdon argues most policymaking is fairly random. Policy change occurs when there is an alignment of a problem, a policy and a political opportunity. This alignment is unpredictable, but when it happens a “window of opportunity” opens meaning policy change is possible. The window is only open briefly, so policy makers have to be ready with solutions because a drawn out development process will take too long. In this model, solutions can be developed which are then touted around looking for a problem to be attached to, or the recommendations of a report can sit for years gathering dust and suddenly burst back to life when circumstances change. If the model is correct, the policy environment is highly unpredictable, and policymakers are simply swept along with only limited scope for control.

Public servants, however, may not simply be passive recipients of events. Many policy scholars argue that there is an iterative and interactive relationship between policymakers and the institutional worlds they operate within. Within the broad field of “New Institutionalism” for example, many strands and individuals make this claim about agency interacting with structure (see for example, Historical Institutionalism and Rational Choice Institutionalism) (Lowndes, Marsh and Stoker 2018; Cairney 2020)[5]

In a truly “bottom up” approach to implementation, Michael Lipsky demonstrates how even those on the front line, like nurses, police officers, social workers, traffic wardens, housing officers, and even university teaching staff(!) can effectively make policy as they go about their work (Lipsky 2010; Birkland 2020)[6]. These “Street-Level Bureaucrats” variously interpret policy, deal with contradictions in it, streamline policy, bend rules, work around policies they dislike, change policy to make it work properly, misunderstand policy, or choose to simply ignore a policy. This could be individuals alone, groups of staff or even whole offices or sections. In the process, the policy being implemented is different to that developed and written down. The ambition of the policy cycle and developing perfect, rational policy, may be admirable, but clearly there are a lot of obstacles to it in the real world.

10 min

Are public servants caught permanently between a desire to make perfect (“rational”) policy and the reality of the real world they operate in?

- Is there anything that can be done to shift policymaking further towards the rational and evidence-based approach of the policy cycle?

- How do your experiences as a policymaker inform your answer?

Business Tools in Government

One impact of the New Public Management changes that have happened since the 1980s (mentioned earlier) was the expectation that government would behave more like the private sector, with a greater focus on value for money, efficiency, measurement and controlling expenditure (Maley, 2021)[7]. This resulted in government agencies starting to use the tools of business, for example producing business cases to help justify proposals.

Another simple tool which became widespread is the SWOT analysis.

“A SWOT analysis tool is one of the most effective business and decision-making tools. SWOT analysis can help you identify the internal and external factors affecting your business.

A SWOT analysis helps you:

-

- build on strengths (S)

- minimise weakness (W)

- seize opportunities (O)

- counteract threats (T)”

(Queensland Government, 2022)[8]

“The methodology has the advantage of being used as both a ‘quick and dirty’ tool or a comprehensive management tool… This flexibility is one of the factors that has contributed to its success.” (CIPD, 2023)[9]

Recommended

40 min

An evidence-based approach is often cited as the best the way of making policy, yet all too often policy is made in ways which fall short of this. This can happen for many reasons. Consider the following questions:

- How and when do you use evidence in your work?

- Thinking about your workplace or policymaking generally, can you think of examples of evidence being used well or badly?

- The idea of evidence-based policy assumes there is broad agreement on what is trying to be achieved and what the priorities are. Who should decide on these and how?

- What are the obstacles to better use of evidence in policymaking? (You may wish to consider some of the ideas in the previous section, especially Herbert Simon and Charles Lindblom).

Deeper Learning

40 min

Rohm, H. (2014). Improving Government Performance Using the Balanced Scorecard to Plan and Manage Strategically. Balanced Scorecard Institute.

Rohm, H. (2020, August 26). Balanced Scorecard for Government. Balanced Scorecard Institute.

Investigate the performance data collection practices in place in your workplace.

- Is there a range?

- How often does each occur?

- How are you asked to contribute to this data collection?

- Do you know what becomes of the data?

- Are you aware of the reporting regime, and to whom is it reported?

- Althaus, C., Ball, S., Bridgman, P., Davis, G., & Threlfall, D. (2023). The Australian policy handbook: a practical guide to the policymaking process (Seventh edition.). Routledge. ↵

- Birkland, T. A. (2020). An introduction to the policy process: theories, concepts, and models of public policy making. New York, NY: Routledge. ↵

- Cairney, P. (2020). Understanding public policy: theories and issues (2nd edition.). Red Globe Press. ↵

- Kingdon, J. W. (2011). Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Longman. ↵

- Lowndes, V., Marsh, D., & Stoker, G. (2018). Theory and methods in political science. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan. ↵

- Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-Level Bureaucracy, 30th Ann. Ed.: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service. Russell Sage Foundation. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610446631 ↵

- Maley, M. (2021) The Executive and the Public Service in A. Fenna & R. Manwaring (Eds), Australian Government and Politics (pp. 61-79) ↵

- : Queensland Government. (2022, December 8). SWOT Analysis. https://www.business.qld.gov.au/running-business/planning/swot-analysis ↵

- CIPD. (2023, July 19). SWOT Analysis. https://www.cipd.org/uk/knowledge/factsheets/swot-analysis-factsheet/#when-to-use-a-swot-analysis ↵