QUT Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework

Contents

Preamble

Alignment with QUT Priorities

How to use this Framework

Graduate Profile

Acknowledgements

Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework Themes

Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework Learning Outcomes

Student Voice

Exemplars, resources

Appendix 1: Cultural Safety Principles

Appendix 2: Glossary

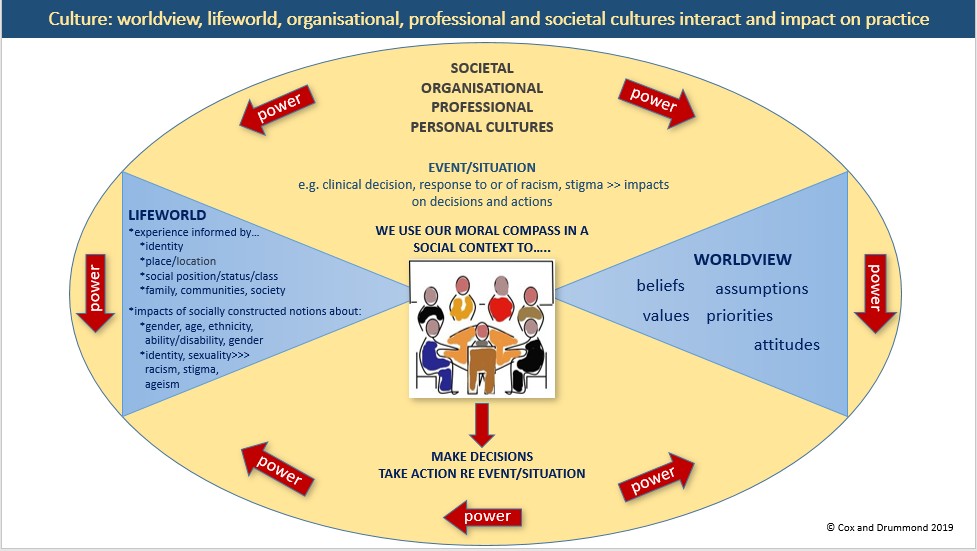

Appendix 3: The Culture Concept Diagram

Appendix 4: Intersectionality

Preamble

The aim of the Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework is to enable a consistent and strategic approach to matters concerning social justice and equity in all Faculty of Health academic programs in line with key QUT policies, visions and strategies, applying the principles of cultural safety.

Cultural safety, a model created by Maori scholar Dr Irahepeti Ramsden and colleagues, is an example of an Indigenous knowledge that is widely applicable as best practice in preparing

graduates to take their place as leaders in social transformation. Informed by critical theories of power and underpinned by social constructionism it prepares graduates to negotiate and address power and privilege imbalances; systemic, scientific and personal racism; and other social processes such as stigma, which create and sustain health inequalities in neo-colonial, neo-liberal societies such as Australia.

The model is deeply relevant for addressing health inequity experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples promoting a strengths based- sociological approach, however it has much broader significance. Its wide applicability is due to its focus on the cultures of health professionals, professions and services as the site of scrutiny and change. These concern everyone,

everywhere. To confront racialisation of some sectors of the population, it challenges the notion that only ‘people of colour’ have ‘culture’ and ‘ethnicity’. It does so by using a broad definition

of personal culture including the interaction between worldviews (values, beliefs, assumptions, and attitudes into which we are socialised), aspects of the lifeworld (social experience, privilege, opportunity) and personal cultural factors such as age, gender, class, ethnicity, and ability (intersectionality). In doing so it simultaneously positions professionals, professions and systems as cultural entities and promotes a grasp of intersectionality and its impacts that can be applied to self and others. This Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework has application to a multitude of service contexts including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, aged care, gender specific services, mental health, LGBTIQ+ and disability services .

Culturally safe organisations dedicate time and resources to establish valued processes to support cultural safety practice by individuals, teams and systems. They accept and acknowledge the impact of their cultures on health outcomes of service users. The practice of cultural safety concerns an ongoing exercise of reflection by health professionals on their personal, professional and institutional cultures and the dimensions of power that inform them. Culturally safe professionals bring to consciousness their values, assumptions, biases and related feelings that often affect clinical decision- making, practice and peoples’ experience of health services. This self-reflective work is essential to gain and maintain trust, which forms the basis of working

partnerships between health services and those we seek to serve.

Cultural safety acknowledges and accepts differences as legitimate and its practice is not about studying other people’s cultures and nor does it concern the ethnicity of health service users, so cultural safety can be decisively distinguished from the various transcultural approaches (cultural competence, appropriateness, capability, awareness and so on). In contrast to these approaches, cultural safety is an explicitly political model, considering how society and its institutions respond to difference making historically situated social determinants of health such as power imbalance, privilege, racisms and stigma key areas of study and action.

Alignment with QUT Priorities

This Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework deeply aligns with two key QUT Priorities Inclusion and Social Justice and Recognising and Fostering Indigenous Australians Excellence. Within these priorities QUT makes a commitment to embrace ethnic and cultural diversity. In the teaching and learning sphere of activity, this reflects a commitment to preparing our students to interact in local and global cultural contexts with respect for diverse cultural perspectives. Engagement with cultural perspectives relates to respecting the ideas, needs, values, viewpoints and social experiences of everyone working in or accessing a service. However, authentic engagement begins with a recognition of yourself as a

bearer of culture. From a curriculum perspective, a dynamic multidimensional concept of culture emphasises critical reflection and a commitment to social justice. These practices equip students to be aware of what is happening in society, producing socially responsible citizens and truly innovative thinkers preparing them to engage in social transformation within and outside their profession in local and global contexts.

FUTURE FOCUS CURRICULUM FRAMEWORK/COURSELOOP

This Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework clearly aligns with QUT Curriculum Design Principles (Courseloop) which requires all courses to embed Real World Learning Features (RWLFs) including Diverse Perspectives and Inclusion and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives.

How to use this framework

This Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework is meant to support and guide curriculum design in the area of cultural safety according to the needs of your context. It is intended to have a companion document demonstrating application to Indigenous contexts and it can readily be applied to gender equity, ageing and other parameters of and social justice, which are key priorities within QUT Blueprint 6.

The Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework captures the key principles to support ALEs, CCs and UCs to embed cultural safety into undergraduate and postgraduate programs according to their specific context.

The Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework presents the learning outcomes at a novice to entry to profession level to assist in building and developing them as they are integrated across the years of a degree.

Each School/Program will be supported to translate the Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework into curriculum and learning design within their own curriculum context.

Graduate Profile

QUT’s Faculty of Health is engaging in inter-professional education and practice, producing graduates responsive to multiple contexts and complex needs and who are confident in advocating for social justice. QUT is committed to produce students able to question conventional knowledge and how professional power hierarchies impact on professionals and practices within and outside their disciplines to take on the challenges of a globalised world.

As an inclusive culturally safe graduate you are a self-questioning, assertive leader, able to take part in hard conversations, as you advocate for service users’ needs and against racisms and other forms of discrimination. You are aware of what is going on around you in society and where you fit within it. You can critique the impacts of the social constructions of health, race, class, age, ability, sexuality and gender on health systems and professional practice. You draw on an appraisal of historical contexts in the light of contemporary policy and practice, and analyse what has or has not changed and suggest ways to bring about change.

You evaluate the workings of your privilege, power and opportunities and those of your profession, establishing a critical understanding of intersectional theory underpinning health and its application in culturally safe practice.

You demonstrate leadership and initiative in challenging the status quo and initiating transformational professional practice of self, others, services and systems. You can confidently construct an argument advocating for the concrete application of cultural safety within your respective discipline/profession and organisation.

Acknowledgements

Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework Working Group: Marian Boman, Leonie Cox, Ali Drummond, Deb Duthie, Alex Dwyer, Shelley Hopkins, Trish Obst

Faculty of Health Cultural Safety and Indigenous Issues School Champions: Marian Boman, Mark Brough, Leonie Cox, Ali Drummond, Deb Duthie, Alex Dwyer, Melissa Haswell Shelley Hopkins, Philippe Lacherez, Jakki Lea, Trish Obst, Fiona Naumann, Tony Parker, Jo Stephens, Helen Vidgen

Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework Themes

The Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework uses the following five themes.

- Theory

- Historical literacy

- Privilege, power and opportunity

- Culture concept

- ‘Self’-reflexivity

Faculty of Health Cultural Safety Curriculum Framework Learning Outcomes

| THEMES | NOVICE | INTERMEDIATE | ENTRY TO PROFESSION |

| critical postmodern theory

*CSP # 2, CSP # 4 |

Demonstrate a beginning understanding of the social construction of health, race and gender. | Examine the influence of social constructionism on the dominant values, assumptions and processes that shape health systems. | Critique the impacts of these social constructions on health systems and professional practice. |

|

historical literacy CSP # 2, CSP #4 |

Demonstrate a foundational knowledge of Australian history in relation to various Australian communities. | Analyse the ongoing impacts of these historical events on contemporary society including the usefulness of health systems. | Appraise historical context in the light of contemporary policy and practice, and critiquing what has or hasn’t changed. |

|

privilege, power and opportunity CSP32, CSP#3, CVSP#4 |

Explain the relationship of privilege, power and opportunity to social outcomes for self and

others. |

Interpret social outcomes (e.g. health and education) in the socio-political context of everyday life. | Evaluate the workings of your privilege, power and opportunities and those of your profession. |

|

culture in CS CSP #1, CSP #3 |

Demonstrate understanding of the culture concept as it is used in CS as it applies to | Demonstrate a practical integration of the grasp of the culture of persons, | Demonstrate a critical understanding of the intersectional theory |

| the culture of persons, professions and organisations | professions and organisations and their impact on health outcomes | underpinning health and its application in CS practice | |

|

‘self’-reflexivity CSP#1, CSP #2 |

Demonstrate a foundational capacity for on-going personal self-reflection | Examine the relationship of self to professionalism and the provision of culturally safe person/client centered practice | Demonstrate leadership and initiative in challenging the status quo and initiating transformational professional practice of self, others and systems. |

|

professional regulation CSP#1, CSP32, CSP#3, CSP#4 |

Demonstrating understanding of how cultural safety relates to respective professional codes and standards. | Interpret professional codes and standards in the application of cultural safety. | Construct an argument advocating for the concrete application of cultural safety within respective discipline/profession. |

*Cultural Safety Principles (CSPs 1-4 see Appendix 1)

Student Voice

Process: present first draft to Faculty Student Advisory Committee 2020.

Exemplars and Resources

Along with the principles and glossary of key terms below, the CSI encourages sharing exemplars and resources.

Appendix 1: Cultural safety Principles [CSP #1-4]

|

PRINCIPLE 1: broad definition of culture of people and organisations |

|

broad definition of personal culture and identity to include lifeworlds and worldviews culture is learned and dynamic all people have culture and ethnicity ethnicity DOES NOT equal culture which includes gender, sexuality, occupation, age, class society and humans are co-creating e.g. race is a social not a biological fact othere are multiple realities and no universally agreed definitions of health organisations /professions/staff groups all work within and have cultures |

|

PRINCIPLE 2: ongoing critical reflection for institutional and personal cultural awareness for social change |

|

extension of ongoing practice of critical reflection and awareness acknowledge that our social position and cultures can impose limitations on practice understand our own beliefs, attitudes and values and their origin acknowledge power and privilege organisations support critical reflection on practice and cultural dominance acknowledge the heritage and ongoing impact of cultural colonial imperialism commit to decolonise institutional and professional practice reflect on colonial history and ongoing health impacts be open to and respect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledges, perspectives and experiences commit to anti- oppressive policy and practice accept that cultural differences exist and are legitimate be open to, respect and include all marginalised people |

|

PRINCIPLE 3: biculturalism |

|

all human interactions have cultural dimensions all interactions between 2 people involve at least 2 personal cultures [+ the culture of the organisation, society] people are not homogenous; those who share a nationality, ethnicity, a generation or other identifiers may have different values, beliefs, priorities, attitudes, socio-political experience |

|

respects uniqueness of individuals and that people and families are the experts on their cultures |

|

PRINCIPLE 4: social justice through partnerships, power sharing, negotiation |

|

service providers and professions are responsible for eliminating attitudes and improving policy, service design and delivery commit to human rights including advocacy for equitable distribution of resources challenge racisms, ageism, sexism, ableism, hetero-dominance, class privilege, ethnocentrisms actively reducing power differences acquisition of trust focus on relationships open, non-judgemental communication underpinned by the social determinants of health and awareness of structural inequality to avoid victim blaming focus on how society treats people differently not on how people differ challenge negative attitudes by those in positions of power in organisational cultures i.e. do not demean, diminish or disempower any person flexible, open staff and services to change dominating practices i.e. safety defined by the users of services |

Citation: Cox, L. (2018). Cultural Safety Principles, SON, QUT. Acknowledgement: These principles synthesised and articulated by Leonie Cox from reading of:

Ramsden, I. (2002). Cultural Safety and Nursing Education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu: A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing. Victoria University of Wellington.

Appendix 2: Glossary

|

Assumptions |

Our automatic responses and established opinions. |

|

Attitudes |

Our beliefs, feelings and values create states of mind (attitudes) about our self, others, the world, activities and so on. These states of mind determine how we behave toward people and situations. For example if someone highly values paid work and believes that paid work is the foundation of happiness, then their attitude toward paid work will be positive and they will engage happily in paid work. Alternatively if someone values leisure or creativity or community service they might hold the belief that paid work takes them from their true purpose in life and their attitude toward it may be negative and they might not want to engage in paid work. |

|

Beliefs |

Beliefs are meanings or fundamental ideas that you have about the nature of the world and that you hold to be true or real but for which there is no generally acceptable evidence. Beliefs usually consider questions of how humans came to be on earth, how the universe came about and how it works. For example someone may believe that aliens are humans’ ancestors but there is no evidence for this proposition. Someone may believe in extra sensory perception but there is no proof of it. Others may believe in creationism but again there is no generally acceptable proof of this. |

|

Cultural Safety |

Critical theory at its most basic seeks to understand and change imbalanced relations of power and domination “The effective nursing of a person/family from another culture by a nurse who has undertaken a process of reflection on [their] own cultural identity and recognises the impact of the nurse’s culture on nursing practice” (NCoNZ 1996, p. 9) |

|

Culture occurs at different levels and is a contested concept because there is no universally agree definition but all cultures are learned, dynamic, changing, strategic, negotiated. There is personal culture, professional/institutional/organisational cultures and societal culture. Personal culture: refers to multiple aspects of our identity (ethnicity, nationality, age, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, education, occupation, ability, class and socio-economic status and political persuasion); our way of life; |

|

|

|

our social experience of belonging, status and opportunity; the values, beliefs, and attitudes that we use to make decisions and respond to situations in everyday life including in professional practice. The concept of personal culture as used in cultural safety focuses on the interaction between the lifeworld [aspects of life as it is experienced] and worldviews [beliefs, values, attitudes, assumptions]. Professional /institutional cultures: the beliefs, values, priorities, sensibilities, ways of doing business, dress, knowledge, jargon/language, techniques, social status and influence, and theories of professions. For example, health care cultures tend to value efficiency, competency, effectiveness, compliance, punctuality, science, intervention and technology and to prioritise completing tasks accurately and quickly. Societal Culture: Whilst there is tremendous variation in the cultural ways of being amongst the members of a nation or society, there are dominating aspects of the society, which make up the dominant culture. Like personal, professional and organisational cultures, societal culture is about power, history, values, attitudes and priorities expressed in the ways things are done (practices). For example, although Australia is considered a secular and multi- faith society, the Christian religion dominates. While it is considered, multi-cultural the English language dominates and ways of doing business throughout society are based on European knowledges, philosophical traditions, pedagogical practices and biomedical practice. |

|

Socially constructed group identification/belonging based on common ancestors (kinship) and history and traditions in language, food, dress etc. |

|

|

Eurocentric |

The organisation of society (such as schools, hospitals) according to western (European) values and priorities which are seen as ‘normal’ and ‘right’ by those espousing them. Organising society according to the values and priorities of one cultural tradition is always at the expense of those of other cultural traditions. An example of eurocentrism in health is the assumption that only the biological parents are Mother/Father, while in some Indigenous societies relatives that western society calls Aunt/Uncles are also known as Mother/Father. |

|

Frame of Reference |

‘The context, viewpoint, or set of presuppositions or of evaluative criteria within which a person’s perception and thinking seem always to occur…,” Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (2nd edn: 1988 at http://www.doceo.co.uk/tools/frame.htm). Our frame of reference is the way we habitually think and the points of view that we hold. |

|

The lifeworld defined as ‘the sum total of physical surroundings and everyday experiences that make up an individual’s world’ (Merriam-Webster Dictionary online at http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lifeworld). |

|

|

Norms |

Generally accepted or expected standards of acceptable and unacceptable behaviour that operate in society. However, norms are trends NOT RULES. For example, an expected norm would be that people hand in someone’s lost property if they find it. Nevertheless, some people do and some people do not! Norms are also standards or occurrences regarded as typical in a society. For example in Australian society, the norm is for many school leavers to go to a coastal area and party, but not ALL school leavers do this. I heard at a colleague’s son’s school the ‘Schoolies’ went to towns in Australia and offer to help with whatever that community needed e.g. cleaning up a park. I wonder if that might become a new norm. |

|

Power Power is a highly contested concept involving deep and ongoing philosophical debates. Power is not a thing that one either has or does not have. It is an aspect of the social relationships between individuals and structures and so we talk of power relationships, and imbalanced power relationships. Those in powerful positions in human relationships have the capacity to influence and control the actions of others. |

|

|

Race |

Race is a social construct not a scientific fact as biologically there is only one human race. Some groups however identify with a notion of race since they have always be catergorised according to an assumed race. They reclaim it as a positive social and cultural identifier. Racialisation is the process of categorising people as being of assumed races. |

|

Racism |

Racism is the practice of using the idea of race to claim that some people are inferior to others. Racism discriminates against people based on the social construct of “race‟. Historically, Anglo-Saxons claimed that they were superior to all other people and that this gave them the right to control other people and to take their land for example. This assumed superiority of some societies over others is called “social Darwinism”. |

|

constructionism |

Social constructionism refers to a group of social theories that consider the relationship between people and society, often sourced to the work of Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann ‘s The Social Construction of Reality (1966). It argues that society creates people and that people create society. It considers the way that society creates gender, ‘race’, age for example along with ideas of health. Social constructions affect human beings. Socially created assumptions circulate; influence the way people are treated, and how they act. For example, the social construction of men includes that they are tough, logical, strong resulting in some not seeking health care as readily as women do, probably contributing to the fact that statistically they die earlier.

|

|

Socialisation |

Socialisation is the process occurring throughout childhood whereby children learn values, beliefs and attitudes and how to act in their context. Families, schools, peers, the mass media and society are socialising agents. When we enter professions, we undergo ‘secondary socialisation’ where we learn the rules, norms, values, beliefs and priorities of the profession.

|

|

Stereotyping |

Stereotyping is making an assumption, often based on a person’s appearance, that they belong to a particular cultural group and that this group is homogenous. Therefore it is assumed (wrongly) that the members of the group can all be expected to hold the same values, beliefs and attitudes and to behave in the same way. For example stereotypes about Australians are that all easy-going (lazy), dress in shorts, singlets or swim wear all the time and swill large amounts of beer constantly. |

|

Values are guiding principles based on aspects of life that are held in high regard. We draw on our values to help us make decisions in life or to help us to decide how to behave in a given situation. Examples of values are honesty, hard work, fairness/equity and so on. So if we are someone who values honesty for example we wouldn’t decide to cheat in an exam or to keep the wallet we found in a taxi. |

|

|

The idea of the worldview is useful as we all have a worldview. We turn to our personal worldview to answer such questions as: How did the world come about? How did I get here? What am I doing here? What is my purpose in life? What happens when I die? Is there life on other planets? However, there is so much difference within cultural groups that the rigid idea that those who identify with the same culture exactly share a worldviews leads to misguided assumptions and cultural stereotypes.

|

|

Appendix 3: The Culture Concept Diagram

Appendix 4: Intersectionality

See,

Victoria State Government Diversity and Intersectionality Framework (2017)

Available,